A new Government Accountability Office (GAO) report claims that, among other issues, the Border Patrol is not efficiently deploying agents to maximize the interdiction of drugs and illegal immigrants at interior checkpoints. I wrote about this here. These checkpoints are typically 25 to 100 miles inside of the United States and are part of a “defense in depth” strategy that is intended to deter illegal behavior along the border. Border Patrol is making suboptimal choices with scarce resources when it comes to enforcing laws along the border. A theme throughout the GAO report is that Border Patrol does not have enough information to efficiently manage checkpoints. Contrary to the GAO’s findings, poor institutional incentives better explain Border Patrol inefficiencies, while a lack information is a result of those incentives. More information and metrics can actually worsen Border Patrol efficiency.

Inefficient Border Patrol Deployments

Border Patrol enforces laws in a large area along the border with Mexico. They divide the border into nine geographic sectors. They further divide each sector into stations that are further subdivided into zones, some of which are “border zones” that are actually along the Mexican border while the remainder are “interior zones” that are not along the border. The GAO reports that this organization allows officials on the zone level to deploy agents in response to changing border conditions and intelligence.

The GAO states that Headquarters deploys Border Patrol agents to border sectors based on threats, intelligence, and the flow of illegal activity. The heads of each sector then allocate agents to specific stations and checkpoints based on the above factors as well as local ones such as geography, climate, and the proximity of private property. The heads of those stations and checkpoints then assign specific shifts to each agent. The time it takes for a Border Patrol agent to respond to reported activity, their proximity to urban areas where illegal immigrants can easily blend in, and road access all factor into these deployment decisions.

All of the above factors that managers and supervisors consider for deployment are reasonable but it is still a management black box. How much does each of these factors matter in determining deployments? Does the relative importance of each factor shift over time or between sectors? How can we tell if one set of decisions is consistently better than another set?

The GAO and other organizations always suggest the same solution to illuminate the black box of Border Patrol agent management decisions: more information. The Border Patrol has about 19,500 agents, about 43 percent of whom can be deployed in the field at any given time, and 143 checkpoint locations along the Southwest border. The GAO has access to extensive data on Border Patrol deployments from the Border Patrol Enforcement Tracking System (BPETS), GPS coordinates for some enforcement operations, seizure information, and the time use of Border Patrol agents by sector when they are on duty. Border Patrol likely has more information available that GAO has not analyzed.

Yet, more information is always insufficient at gauging the efficiency of agent deployment at checkpoints. The recent GAO report notes that “checkpoints’ role in apprehensions and seizures is difficult to measure with precision because of long-standing data quality issues” that the GAO first complained about in 2009. Checkpoints did not consistently report apprehensions as some included any apprehension within a 2.5‑mile radius of a checkpoint as apprehended by the checkpoint, while others had different definitional radii and reporting standards. As a result, the number of apprehensions and seizures cannot be determined. The data reporting “issues continue to affect how Border Patrol monitors and reports on checkpoint performance results” despite several memoranda that were supposed to remedy the data collection issues. Border Patrol finally created the Checkpoint Program Management Office (CPMO) in 2016 that is supposed to remedy data collection inconsistencies.

The GAO report calls for more detailed information, such as distinguishing whether an illegal immigrant detention occurs “at” rather than “around” a Border Patrol checkpoint. The GAO also suggests accurate “workplace planning needs assessments” to make sure that checkpoints are manned and operated properly. GAO asks Border Patrol to implement internal controls to ensure data accuracy, consistency, and completeness to overcome problems like supervisors who are not required to update BPETS if their actual deployments differ from those planned and recorded in BPETS. Border Patrol should also study the impact of checkpoints on local communities when considering agent deployment. Finally, GAO reiterates its call for an accurate “workplace planning needs assessment” to make sure that checkpoints are manned and operated properly. How Border Patrol is supposed to integrate these new metrics with existing metrics is a mystery.

The Incentive to Patrol the Border

Government law enforcement agencies do have difficult or, in many cases, impossible jobs. Interrupting supply and demand by stopping the flow of unlawful drugs and illegal immigrants into the United States is as Sisyphean a task as Soviet criminal investigators who attempted to stop the black market in gasoline or food. More information won’t remedy the agent deployment problems at Border Patrol, CBP, or any other government agency. The problem with these agencies is not a lack of information but bad incentives.

The performance of government agents isn’t measured by profit and loss as it is in the private sector but by political factors. In the language of economics, Border Patrol faces a principal-agent problem. Principals are the owners and the agents work for them. That sounds simple enough but principals and agents have different incentives. For instance, principals in private enterprise want to maximize profit while many of their agents (workers) want compensation for doing as little as possible or diverting resources into their own pockets. Principals thus have to structure compensation and manage in such a way as to align the incentives of workers and employees through profit sharing, other financial incentives, or through myriad other ways to mitigate these problems. Information is vital to mitigating a principal-agent problem (it can never be fully solved) but more information by itself without the incentive to use it wisely is wasted.

The Border Patrol principals are the politicians who ultimately determine its budget and appoint the heads of the organization. The incentive of the principals is to stay in elected office by winning elections. Border Patrol employees are the agents who supposedly work for the principals. Satisfying political constituencies has little to do with actually enforcing the law as written. For instance, enforcement of immigration laws typically declines during times of economic growth because businesses demand more workers and labor unions complain less about illegal immigrant workers. No lobbying of Congress is necessary, merely the reactions of Border Patrol employees to changing economic circumstances in anticipation of what they think politicians want.

What those politicians want changes over time based on what they think the electorate wants. In the past, economic growth was a better predictor of immigration enforcement. Now, immigration-induced changes in local demographics, cultural complaints, and the idea that immigrants and their descendants will vote against incumbent political parties also drive support for immigration enforcement. Thus, removing illegal immigrants is the latest iteration of the Curley Effect. Countering this trend are pro-immigration local policies like Sanctuary Cities, as well as states like Illinois and California that restrict local police cooperation with federal law enforcement.

More Information Can Worsen Management

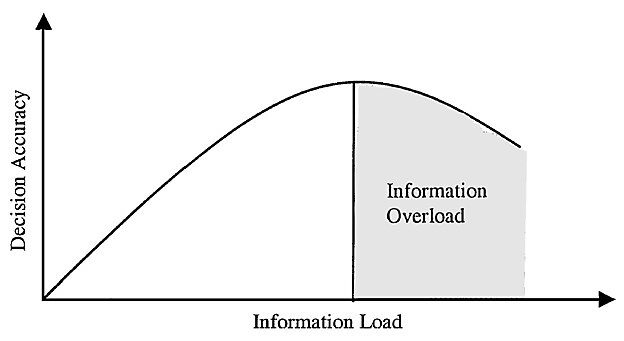

The call for more information and better metrics for measuring border security is well intentioned but it can also backfire. Some information is required to make accurate decisions but, beyond a certain point, too much information can produce information overload, whereby decisions become less accurate as the decision maker learns more (Figure 1). Information beyond the overload point will confuse a decision maker, affect his or her ability to set priorities, and worsen recall of prior information. A fundamental concept in economics is scarcity, which occurs when there is not enough supply of a good to satisfy all demand at a price of zero. Information overload is a reminder that human attention span, information processing capacity, and accurate decision-making ability are also scarce resources.

Figure 1

Information Overload as the Inverted U‑Curve

Source: Martin J. Eppler and Jeanne Mengis.

Information overload can take several forms. Some scholars emphasize how much time it takes to absorb new information, which can diminish the accuracy of decisions that require timely action. That case is most similar to the timeliness of intelligence reports in guiding Border Patrol agent deployment. The value of most intelligence depreciates rapidly and, if it is accurate, must be quickly acted upon to have an effect. Other scholars focus on the quality of information, as it is difficult to measure that without first absorbing it and comparing it to other information. Estimates of the size of black markets, a crucial metric for Border Patrol, are fraught with errors and it is nearly impossible to tell which one is correct. Tasks that are reoccurring routines produce less information overload than more complex and varied tasks. As mentioned above, the organizational design of a firm is another important factor that influences information overload.

Smugglers and illegal immigrants compound the problem of information overload as they change their behavior in response to Border Patrol policies. Smugglers and illegal immigrants rarely want to be apprehended so they shift away from patrols or areas where there is more enforcement. In the mid-2000s, illegal Mexican border crossers moved east from California and west from Texas into Arizona because of border security. More enforcement in Arizona after 2010 then shifted illegal immigrant entry attempts back east toward Texas. Their constant movement and reaction to Border Patrol and immigration enforcement generally creates more complexity and information that the agency must process.

The symptoms of information overload are a lack of perspective, cognitive strain and stress, a greater tolerance for error, low morale, and the inability to use information to make a decision. Those symptoms are all common at Border Patrol and its parent organization, the Department of Homeland Security. In terms of a lack of perspective, the chaos below the border is a supposed “existential threat.” Meanwhile, the tolerance for performance and discipline problems in Border Patrol personnel has festered for over a decade, producing numerous errors of all kinds. Morale has historically been low in Border Patrol and has only risen recently due to the election of President Trump.

One common reaction to information overload is that decision makers become highly selective, ignore vast amounts of information, and cherry pick that information which confirms their biases. Information never speaks for itself and it must always be interpreted and applied. By increasing the quantity of information available to managers and supervisors at Border Patrol, their actions could become more erratic and less efficient because they will be able to pull from a vaster array of justifications for their decisions. Like any other self-interested actors, Border Patrol will always select and interpret information to justify the actions they want to undertake while discounting information that supports another course of action. The principal-agent problem means that this rarely gets corrected.

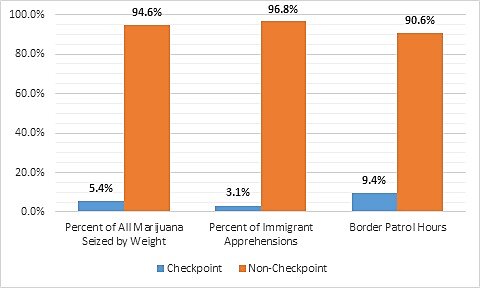

For instance, 9.4 percent of Border Patrol hours were spent manning checkpoints from 2013–2016. Yet those checkpoints were only responsible for, at most, 3.1 percent of all illegal immigrants apprehended by Border Patrol in those years and 5.4 percent of all marijuana seizures by weight (Figure 2). That might look like an inefficient allocation of Border Patrol agents, but a smart manager can always argue the opposite by saying, as an example, “we don’t catch many illegal immigrants at checkpoints because checkpoints are so effective at deterring illegal immigrants from even trying to use to the road. Imagine how many there’d be without the checkpoints!” That manager would have a good point.

Figure 2

Percent of Illegal Immigrant Apprehensions & Drug Seizures Made by Border Patrol by Location, 2013–2016

Source: Government Accountability Office, p. 41.

A border wall that diverts illegal immigrants into the interior and away from cities can be used as support for a longer wall to “extend the gains” or as support for no wall at all because “illegal immigrants are just diverted to more remote areas where agents now have to patrol with greater hazards.” More information and data could worsen the decisions made by Border Patrol managers.

Back to Incentives

Firms employ countermeasures to information overload, such as better technology and algorithms to select the best data, but the countermeasures are only effective if the managers want to make more accurate decisions. The desire to make accurate decisions in a large organization comes back to incentives, which government agencies have a very difficult time aligning with the stated intent of the law.

If the incentives to act efficiently are in place then the actor has the incentive to discover the information necessary to carry out his task. But perfect information cannot fix poor incentives and, in fact, can make them worse. Rather than focusing on hiring statisticians, econometricians, and other technocrats to create ever-new metrics to judge government efficiency, Congress should think carefully about aligning incentives to get the outcomes they want. That is a near-impossible job for politicians to tackle so, in most cases, they should just pull back the reach of federal law enforcement to focus on a handful of tasks.

Conclusion

The best information in the world cannot compensate for poor incentives and can make government management less efficient by providing cover for any choice. Government agents are not usually malevolent, or at least any more so than the rest of us, but they have incentives to satisfy political demands. Private firms that behave in these ways often fail or earn lower profits unless they are bailed out by the government, which is usually the source of these poor incentives in the first place. More metrics can even worsen efficiency. We should look to deeper structural reforms of government agencies rather than continuing to appeal to a priesthood of statisticians and econometricians to produce information to guide us.