Over the summer, The New York Times published an error-ridden piece on Michigan’s charter schools that it has yet to retract. Now, the NYT is doubling down with another piece adding new errors to old ones. The errors begin in the opening sentence:

Few disagreed that schools in Detroit were a mess: a chaotic mix of charters and traditional public schools, the worst-performing in the nation.

This is editorializing thinly veiled as “news.” In fact, lots of experts disagreed with that statement. The original NYT piece received a wave of criticism from national and local education policy experts, charter school organizations, and other journalists. As I explained at the time, the central premise of the NYT’s takedown on Detroit’s charter schools was an utter distortion of the research:

The piece claims that “half the charters perform only as well, or worse than, Detroit’s traditional public schools.” This is a distortion of the research from Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO). Although the article actually cites this research – noting that it is “considered the gold standard of measurement by charter school supporters across the country” – it only does so to show that one particular charter chain in Detroit is low performing. (For the record, the “gold standard” is actually a random-assignment study. CREDO used a matching approach, which is more like a silver standard. But I digress.) The NYT article fails to mention that the same study found that “on average, charter students in Michigan gain an additional two months of learning in reading and math over their [traditional public school] counterparts. The charter students in Detroit gain over three months per year more than their counterparts at traditional public schools.”

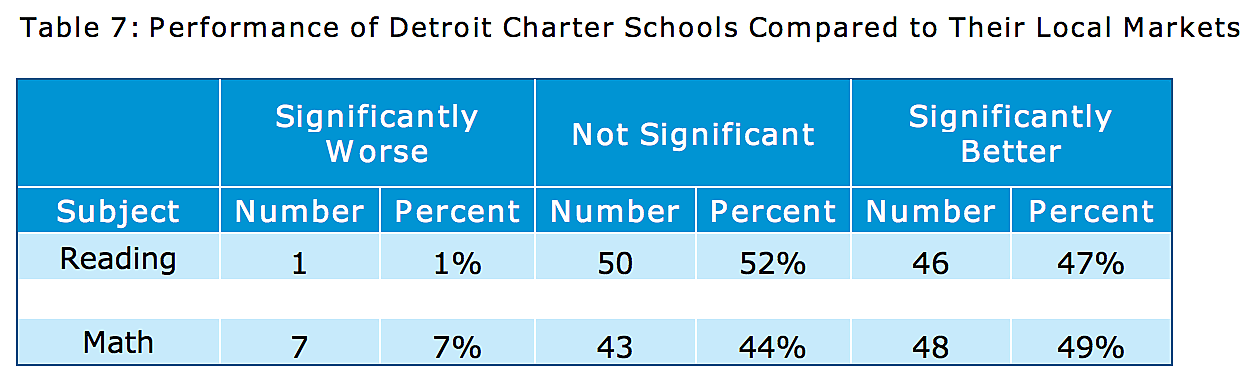

As shown in this table from page 44 of the CREDO report, nearly half of Detroit’s charter schools outperformed the city’s traditional district schools in reading and math scores, while only one percent of charter schools performed worse in reading and only seven percent performed worse in math.Grouping the very few underperforming charters with the approximately half of schools that perform at roughly the same level as the district schools distorts the picture. It’s just as fair to say that more than nine out of ten Detroit charters performed as well or better than their district school counterparts. The most accurate description would note that about half of Detroit’s charters outperform their district school counterparts, about half perform roughly the same, and a very small number underperform. […]

[NYT reporter Kate] Zernike is still claiming that the CREDO study “does not consider Detroit[’s charter sector] stellar,” even though both the 2013 CREDO study of Michigan’s charter sector and the 2015 CREDO study of charters nationwide found that, on average, Detroit’s charter schools outperformed the district schools that their students would otherwise have attended. Indeed, one even called Detroit’s charter sector “a model to other communities.”

Nevertheless the NYT has resurrected its spurious claims to attack Betsy DeVos, the president-elect’s pick for Secretary of Education. In the NYT’s telling, DeVos was responsible for killing a bill that would have imposed some sort of regulations on Michigan’s charter schools that supposedly would have improved the system:

So city leaders across the political spectrum agreed on a fix, with legislation to provide oversight and set standards on how to open schools and close bad ones.

But the bill died without even getting a final vote. And the person most influential in killing it is now President-elect Donald J. Trump’s nominee to oversee the nation’s public schools, Betsy DeVos.

Her resistance to the legislation last spring is a window into Ms. DeVos’s philosophy and what she might bring to the fierce and often partisan debate about public education across the country, and in particular, the roles of choice and charter schools.

The bill’s proposals are common in many states and accepted by many supporters of school choice, like a provision to stop failing charter operators from creating new schools. But Ms. DeVos argued that this kind of oversight would create too much bureaucracy and limit choice. A believer in a freer market than even some free market economists would endorse, Ms. DeVos pushed back on any regulation as too much regulation. Charter schools should be allowed to operate as they wish; parents would judge with their feet.

The idea that DeVos thinks “any regulation” is “too much regulation” is sheer nonsense. As I’ve detailed before, regulations in Michigan limit the ability of charter schools to set their own mission (e.g., they must be secular), mandate that they administer the state standardized test, forbid them from setting their own admissions standards, forbid them from charging tuition, limit who can teach in the schools, limit the growth of the number of schools, and so on. Calling this regulatory environment the “Wild West” is downright Orwellian.

The NYT piece never once lists any of the regulations to which Michigan’s charter schools are already subject, nor does it cite any education policy analysts who disagree with the reporter’s spin regarding Michigan’s charter sector. (The one dissenting voice was only quoted saying that DeVos “never said choice and choice alone is a panacea.”)

And what exactly did DeVos object to? More than 20 paragraphs into the article, the NYT finally explains:

But the provision that proved most controversial to the DeVoses would have established a Detroit Education Commission, appointed by the mayor. With three members from charter schools, three from the traditional public schools and one an expert in educational accountability, the commission was to come up with an A‑to‑F grading system for all schools, and evaluate which neighborhoods in the city most needed schools.

In other words, DeVos objected to giving district school officials and their political allies the power to regulate and even close down their competition. Why, she’s a veritable Ayn Rand!

Yet again, The Times fails to cite any education policy experts who were skeptical of the proposal or sympathetic to DeVos’s position. Moreover, in the antepenultimate paragraph, someone working for a DeVos-funded education advocacy organization in Michigan explained that DeVos supported the final version of the bill, which did not contain the commission but did “allow the state to close the [charter] schools at the bottom of existing state rankings,” putting lie to the reporter’s spin that DeVos thinks “any regulation is too much regulation.”

New York Times readers deserve better.