Yesterday, I shared some reflections on a recent House Select Committee hearing I participated in, on why I thought progressive claims of the U.S. suffering from monopsony labor markets were seriously flawed. But if I disagreed with these witness arguments, I was left just as skeptical of their assertions on the impacts of industrial concentration on inflation.

MONOPOLY POWER DRIVING INFLATION

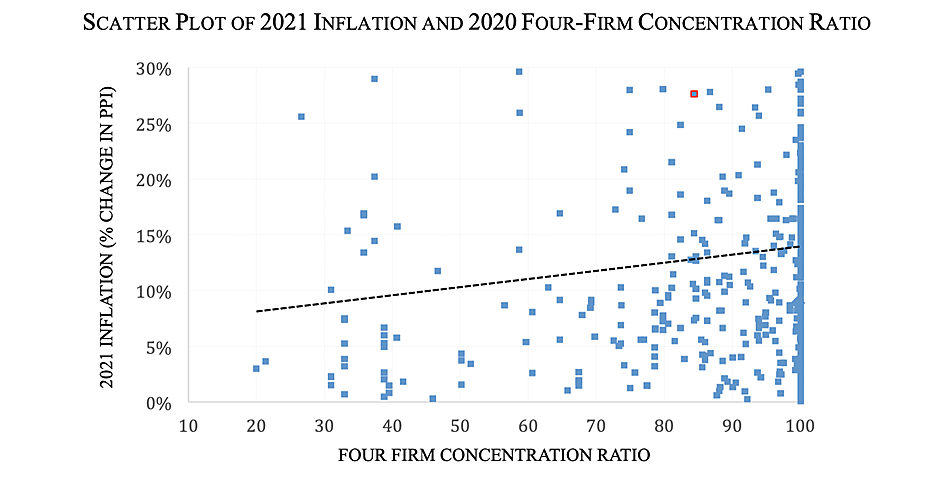

My fellow witness Hal Singer presented correlations (see chart below) purporting to show that more highly concentrated industries had seen faster price rises during 2021, supposedly lending credence to the idea (encouraged by the White House) that a large dose of the inflation we’ve seen was the choice of greedy companies’ pricing power. I had never heard a theory for why concentrated market power might lead to rising prices, as opposed to just a higher level of prices for an industry. But Dr. Singer argued that a dose of inflation helps companies to overcome a coordination problem—the change in prices greases the wheels for firms in an industry to implicitly collude and raise prices simultaneously, including through public statements.

Like most economists since the 1970s, I’ve long been skeptical that nationwide concentration measures like this tell us anything interesting about the nature of actual competition in relevant product markets. A firm might dominate a particular market simply by winning the competitive process through superior productivity or better products. More importantly, plenty of relevant product markets (for thinking about the true level of competition) are very local or global in terms of their geography.

Hal Varian pointed out several years ago that Motorola was the only cell manufacturer in the U.S. A national measure of cell manufacturing concentration would suggest that they monopolized the market. Clearly, this is nonsense, given most phones are imported.

Meanwhile, for most retail and service industries, meaningful competition occurs in very local geographic regions. The work of Esteban Rossi-Hansberg and others has shown that as national concentration measures rise, concentration in local markets falls. If a Walmart opens in every town, the national market becomes more concentrated, but unless this entry crowds out another provider entirely in each location, concentration locally could well fall as consumers have more options. This expansion of productive firms into more regions is exactly what has happened across many sectors.

National concentration measures are therefore poor guides to relevant market power under the best of circumstances. But Singer’s correlation suffers from other difficulties. He only examined market concentration based on publicly traded companies, of which there are only around 5,000 in the U.S. Given there are over 30 million businesses who fill out tax returns contributing to the competitive process, this focus on a subset of firms is clearly inadequate for considering market power.

As a result of this omission, in fact, we see amazing bunching at the 100 percent four-firm market concentration ratio on the right side of his chart – i.e. a slew of industries where four firms are said to dominate the entire market. You can see from looking at this 100 percent concentration ratio that 2021 price changes have been dramatically different across the industries notionally believed to be the most concentrated.

Unsurprisingly, given the dispersion of these observations, the overall correlation between this flawed measure of market concentration and price hikes appears to be very low, and given the other data problems, I don’t believe much of a conclusion can be drawn from it at all. This is before acknowledging that there may also be other confounding factors affecting both these variables anyway, such as if concentrated industries disproportionately rely on transportation, thus suffering more from the recent oil and gas shocks that might also be expected to put upward pressure on prices.

The political imperative to pin the blame on companies for inflation was clear throughout the hearing. Democratic witnesses (and politicians) seemed to talk as if the “what caused inflation?” debate was really a discussion over whether wage increases or market power was responsible for this past year’s rising price level. The fact that corporate profits relative to national income increased alongside prices, they suggested, showed that firms actively decided to raise their prices beyond their rising cost base. Given this was their decision, are companies not responsible for inflation?

No. In fact, as my colleague George Selgin has outlined, that prices went up alongside profits instead reflects the fact that both the inflation rate and corporate profits are affected by the growth rate of aggregate nominal spending, which fell in the early stages of the pandemic and then has surged as spending rebounded and government institutions engaged in unprecedented policies to boost it. Indeed, this used to be the Keynesians’ orthodoxy—that macroeconomic stimulus works by raising aggregate demand for goods and services, pumping prices and firm profitability, and thereby jumpstarting the economy as firms race to meet this demand with increased supply.

Democratic witnesses instead now want us to believe that the macroeconomic policies of the two years were beneficial to the economy through this sort of demand-increasing effect, but simultaneously that this has nothing to do with inflationary pressure and that firms could have kept their prices down in the face of the spending spike these policies helped generate. Such a course of mass suppression of price signals in light of rising spending, relative to potential output, would have created massive economy-wide shortages.

The truth is, we don’t need to conjure up complex theories about market concentration to explain our current inflation. The supply-side of the economy was damaged by COVID-19 and its aftermath. Politicians passed historic stimulus bills and the Federal Reserve accommodated these with expansive policy for too long. Nominal spending growth soared relative to the uplift in the productive potential of the economy and now its past trend, which drove up prices, as well as profits in the short-term (as companies’ wages and some other costs tend to be stickier or lag). Indeed, one recent Federal Reserve bank study suggests 3 percentage points of inflation by the end of 2021 might be explained by fiscal support measures.

Committee chair Jim Himes was keen to explore the idea that some companies had publicly blamed price rises on rising wage costs, but that profit margin increases belied this claim. Yet this isn’t the smoking gun he suspects. Over time, wages and other costs will indeed calibrate to a higher aggregate price level driven by higher spending – meaning any short-term profitability spike will dissipate. The economy is not static: company officials are constantly updating their priors about what their costs will look like in future and have to account for losses in downturns. In the face of nominal spending shocks, price and corporate profits would be expected to rise first before wage increases filter through over time.

If the Democratic witnesses don’t like seeing corporations making huge short-term profits, and are worried about high inflation, then rather than telling corporations to quit being “greedy,” they should bemoan the macroeconomic failures that meant the nominal GDP growth rate has been unstable.

And though inflation is a macroeconomic phenomenon, a more fruitful agenda for policymakers than blaming companies would be to undo policies they control at the federal, state, and local level that raise the cost of important goods and services. Land use planning and zoning laws, childcare regulations, tariffs on footwear and clothing, agricultural subsidies, and occupational licensing laws, all drive up product prices of important goods that lower income households spend disproportionately on.