Having considered the Fed’s pre-crisis approach to monetary control, with its emphasis on interest-rate targets reached with the help of open-market operations, we must now come to grips with the quite different methods it has been employing since, and how the switch to them came about.

The story of that switch must surely rank among the great tragicomedies of monetary history, for despite what many Fed officials have suggested, the Fed wasn’t forced to abandon conventional interest rate targeting for reasons entirely beyond its control. Instead, it was compelled to give-up old-fashioned rate targeting in part because of its own, obstinate refusal to practice such targeting responsibly.

Explaining what happened isn’t easy, so brace up!

The Futility of “Unnatural” Monetary Policy

As should be evident by now, the Fed’s ability to achieve any given federal funds rate target depends on that target’s consistency with the underlying, “natural” funds rate. If, for example, the Fed pours fresh reserves into the banking system, by means of open-market security purchases, to combat a tendency for the effective funds rate to climb above its target, where that target is itself below the “natural” funds rate, its effort will eventually fail, because the fresh reserves will sponsor increased bank lending and investment, which will in turn increase spending on, and prices of, goods and services. The demand for credit will likewise increase, as people must borrow more to finance purchases of more costly goods. Rates will therefore tend to go up after all.

The Fed might try to keep rates from increasing through further rounds of reserve creation. But it would only end up repeating the same process: like a dog chasing its own tail, the Fed would be engaged in a hopeless quest. And should it persist through further rounds, or (what’s worse) accelerate its rate of reserve creation, it will only succeed in causing an equally persistent, if not accelerating, rate of inflation. Because persistent inflation must eventually translate into heightened inflation expectations, interest rates, instead of being lowered, will end up becoming higher than they would have been if the Fed hadn’t fought the increase at all. Anyone who recalls, or has studied, what happened to U.S. interest rates during the 1970s, knows what I’m talking about.

Any Fed attempt to enforce an excessively high rate target is also bound to be self-defeating, for similar reasons. The artificially high target target will mean excessively tight money, which will in turn cause lending, spending, and prices to decline, other things equal. The slackening of demand for goods and services will have as its counterpart a like slackening of demand for credit that will defeat the Fed’s efforts by pushing rates down again. Unless the Fed changes its strategy, market interest rates, instead of staying put, will end up falling even lower as deflation and expectations of its persistence take root.

Black October

It was this last scenario that played out during the last half of 2008. Because it did so against the background of an ongoing decline in real, natural interest rates, the result was that the equilibrium, nominal federal funds rate was driven to zero, and perhaps even into negative territory, compelling the Fed to completely abandon its conventional methods of monetary control.

Although the Fed lowered its federal funds rate target aggressively between the fall of 2007, when it stood at 5.25%, and early May of 2008, once the target was down to 2 percent, it resisted making any further cuts. More importantly, it refrained from making such net open-market purchases as it traditionally relied upon to assist in achieving a lowered rate target by adding to the supply of bank reserves. Instead, as part of its effort to keep the funds rate at 2 percent, the Fed auctioned-off Treasury securities to compensate for, or “sterilize,” its emergency lending programs, subtracting as many reserves from the banks that bought those Treasuries as its emergency loans were supplying to other, more troubled banks.

When, starting in September 2008, the Fed ramped-up its emergency lending, it no longer had enough Treasuries on hand to keep its balance sheet from ballooning. It remained determined nonetheless to resist any monetary loosening. As alternative ways to keep its emergency lending from adding to the general availability of credit, it first arranged to have the government accumulate deposits with it, and then started paying banks to do the same. Instead of keeping a lid on the monetary base, in other words, the Fed tried to keep money tight by reducing the reserve-deposit multiplier.

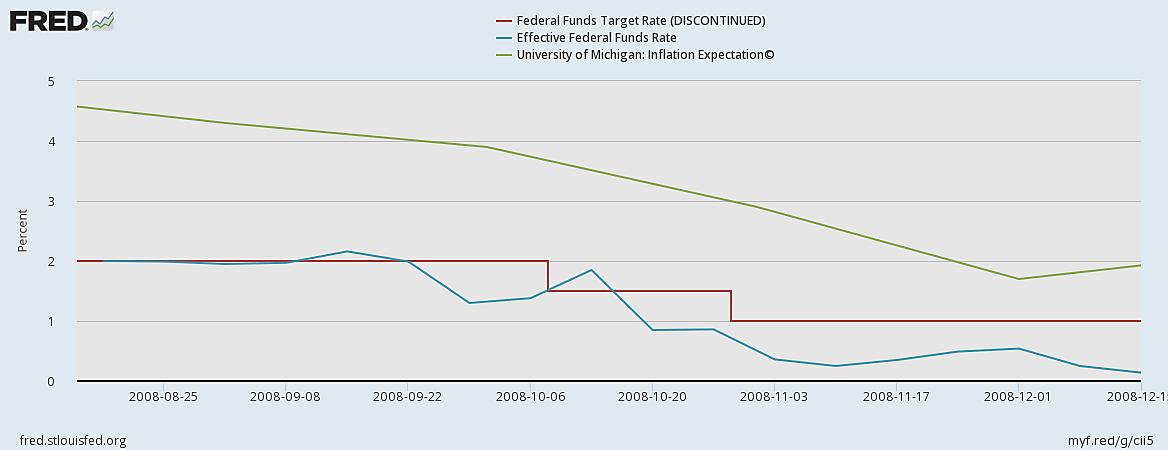

But if the Fed’s aim was to keep the effective funds rate from falling below 2 percent, its efforts were in vain. As the chart below shows, as market conditions worsened, the effective Fed funds rate (blue line) did in fact fall below the Fed’s target (red), from which it then tended to drift further and further.

Disinflation Takes its Toll

Instead of helping to counter the tendency of market rates to decline (for longer-term interest rates were also falling at this time), the Fed’s insistence on maintaining what, in retrospect at least, was an excessively tight stance, reinforced that tendency, by putting a brake on lending and spending, and by contributing thereby to falling inflation expectations. By mid-2008 and the end of that year, according to the University of Michigan’s survey of consumers’ year-ahead inflation expectations, the expected rate of inflation (green line) had fallen from over 4.5 percent to just 2 percent, which meant that, even had there been no downward decline in real natural rates during that time, nominal natural rates would have declined considerably.

Although, as the chart also shows, the Fed did finally cut its rate target again — twice — in October, those cuts were essentially meaningless, because they weren’t accompanied by any increase in the Fed’s open-market purchases. Instead, the only reserves the Fed was creating continued to be those it created as a consequence of its emergency lending. As James Hamilton observed at the time,

the [fed funds] target itself has become largely irrelevant as an instrument of monetary policy… . There’s surely no benefit whatever to trying to achieve an even lower value for the effective fed funds rate. On the contrary, what we would really like to see at the moment is an increase in the short-term T‑bill rate and traded fed funds rate, the current low rates being symptomatic of a greatly depressed economy, high risk premia, and prospect for deflation.

What we need is some near-term inflation, for which the relevant instrument is not the fed funds rate but instead quantitative expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet. …I would urge the Fed to be buying outstanding long-term U.S. Treasuries and short-term foreign securities outright in unsterilized purchases, with the goal of achieving an expansion of currency held by the public, depreciation of the currency, and arresting the commodity price declines.

But the last thing we should expect to do us any good would be further cuts in the fed funds target

You tell it, brother!

Nor did the Fed relax its efforts to prevent the reserves it did create from contributing to the overall volume of bank lending, overnight or otherwise. Indeed, it was while the Fed was making its last “symbolic” changes to its fund rate target that the reserves being piled-up by the Treasury as part of its multiplier-shrinking Supplementary Finance Program reached their peak of just under $560 billion.

Why the sham? Why didn’t the Fed really ease its policy stance aggressively, as it would have had it set and seriously pursued rate targets consistent with underlying market conditions? It’s here that tragedy meets comedy: Fed officials believed that, instead of countering declining inflation expectations, further easing would, by pouring more funds into the overnight market, only serve to further reduce the effective funds rate, eventually lowering it to its zero lower bound. Once it got there, the officials feared, the Fed could lower it no further, and so would find itself out of depression-fighting ammunition.

The Fed’s reasoning, so far as it went, was sound enough: the initial consequence of Fed easing would include an increase in the supply of overnight funds, and a corresponding tendency for the effective funds rate to decline still further. The problem was that this reasoning didn’t go nearly far enough. Fed officials failed to consider how traditional easing — meaning not just more aggressive cuts in the fed funds target, but cuts backed-up by more aggressive open-market purchases — would eventually boost both actual and expected levels of spending, and how, by doing so, it would end up buoying rates instead of suppressing them. Just as a rising tide lifts all boats, a general increase in spending, and especially an increase in the expected growth rate of spending, lifts demand schedules in all markets, including markets for all sorts of loans.

The Fed was, nonetheless, determined to keep a lid on bank lending, overnight or otherwise. When it could no longer do that by sterilizing its emergency lending, it turned, as we’ve seen, to other measures, including paying interest on bank reserves to discourage banks from lending them out.

From Floor to Ceiling…

Fed officials originally hoped that the interest rate on reserves, and particularly on excess reserves, would serve as a floor on the effective federal funds, because banks would have no reason to lend reserves overnight for less than they could earn by holding on to them: the rate would therefore serve to keep the effective funds rate from reaching its zero lower bound, even if it proved incapable of keeping that rate from falling below the Fed’s target.

But that expectation also turned out to be mistaken: because some Government Sponsored Enterprises, including Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks, kept deposits at the Fed, but weren’t eligible for interest payments on those deposits, they were happy to lend their Fed balances to banks overnight at rates below what the banks were earning on their own balances, and the banks were no less happy to oblige them. As the total volume of reserves continued to grow, first in response to further Fed emergency lending, and then in consequence of several rounds of Quantitative Easing, it also became unnecessary for banks themselves to borrow reserves unless they could profit by doing so on the difference between the rate they earned on deposits and the rate they paid on them. The result of all this was that, instead of serving as a floor on the effective funds rate, the interest rate paid on excess reserves ended up becoming a ceiling!

Moreover, the logic underpinning the Fed’s desire to put an above-zero floor on the effective federal funds rate was tortured. To see why, suppose there had been no GSEs with Fed account balances. In that case, no bank would have lent funds overnight for less than the interest rate on reserves, so that the rate would indeed have constituted a floor of sorts. But what difference would that have made? In what sense, apart from a trivial one, would it have solved the so-called “zero lower bound” problem? Yes, it meant that Fed easing no longer posed the risk of driving the fed funds rate to zero, even in the short run. But it did so only by assuring that such easing would cease to have any repercussions, save that of adding to banks’ excess reserves, as soon as the effective funds rate ceased to exceed its new, positive floor. It was as if, out of concern for would-be jumpers, the designers of a skyscraper decided to construct a broad veranda around their building’s second floor, so as to prevent the jumpers from ever hitting the ground.

In any case, the Fed quickly discovered that the interest rate on excess reserves established an upper bound to the effective fed funds rate, while its official rate target, which still hovered well above the effective rate, had become perfectly meaningless. Before the year was over, it formally abandoned that single-valued target. A brave new era of monetary control thus began.

…and from Target to Range

As the old saw goes, if life hands you a lemon, make lemonade. So far as the Fed’s monetary control efforts were concerned, the months starting with Black October were one great lemon harvest. The lemonade followed, sure enough, in the shape of the Fed’s switch from setting a single-value federal funds rate target that it could no longer strike to announcing a fed funds target “range” it couldn’t miss, with the rate of interest on excess reserves serving as the range’s upper bound, and zero as its lower one.

Considering how narrow the range was, the Fed’s new approach may not seem all that radically different from traditional rate targeting. But the appearance is deceiving: in fact, the switch marked a sea change in the Fed’s methods of monetary control.

How so? So long as the Fed took it seriously, the old ffr target operated as a signal to the Fed’s open-market desk, instructing the manager on the required adjustments to the course of the Fed’s open-market purchase. Changes to the funds target were, in other words, a mere headliner to the main, open-market events. By December 2008, that was no longer the case. The Fed’s new fed-funds target range, instead of giving the open-market desk its marching orders, was one in which the effective federal funds rate was bound to fall, no matter what the open-market desk in New York was up to. To both alter the target range, and guarantee that the effective funds rate still fell within it, the Fed had only to alter the interest rate it paid on bank reserves. In its new guise, interest rate targeting, to still call it that, had become entirely divorced from open-market operations, and hence from any actual adjustments to the supply of currency or bank reserves.

In changing the rate of interest on excess reserves, and hence the funds rate target range, the Fed was, to be sure, still exercising monetary control of a sort. But it was a very different and untested sort of monetary control that worked, not by altering the supply of base money, and especially of bank reserves, but by influencing the reserve-deposit multiplier. Other things equal, a higher rate of interest on excess reserves would encourage banks to maintain higher reserve ratios, and this would be a form of monetary tightening. But just how much tightening any given increase in the rate would inspire was hard to say. Nor did the Fed quickly put its new mechanism to the test. Instead, it left its original fed funds target range, with its 25 basis point upper and 0 lower bounds, unchanged until December 2015.

Quantitative Easing

As I’ve said, in replacing its traditional federal funds target with a new target range, the Fed severed the traditional connection between funds rate targeting on the one hand and open-market operations on the other. But that didn’t mean that it ceased to engage in open-market operations, including long-term ones involving outright asset purchases. On the contrary: the Fed’s abandonment of conventional interest-rate targeting coincided with the first of several rounds of what Fed officials referred to as “Large Scale Asset Purchases,” and what the rest of the world calls “Quantitative Easing.”

Despite the torrents of ink that have been devoted to theories rationalizing or otherwise assessing the workings of Quantitative Easing, in essence this “unconventional” monetary policy is nothing more than a name for central bank open-market purchases undertaken without reference to a particular fed funds rate target, that is, purchases that are not aimed at moving the effective fed funds rate to some specific level. Instead of picking a rate target and instructing the open-market desk to buy as many securities as it takes to hit the target, the Fed plans to buy some particular quantity of securities — hence “quantitative” easing.

According to the conventional reckoning, the Fed has engaged in three rounds of quantitative easing, since known as QE1, QE2, and QE3. QE1, which ran from December 2008 to June 2010, added $2.1 trillion, mainly in Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS), to the Fed’s balance sheet. For QE2, which ran from November 2010 until June 2011, the Fed bought $600-billion worth of Treasury securities. QE3, finally, began in September 2012, and consisted of an open-ended program of securities purchases, starting with $40 billion in MBS per month, and supplemented, beginning in December 2012, with monthly purchases of another $45 billion in long-term Treasury securities. In all, between December 2008 and October 2014 the Fed purchased securities worth not quite $4 trillion, or about 4.5 times its total assets just prior to the crisis.

That Quantitative Easing had nothing to do with interest targeting was made especially evident by the fact that the Fed left its original federal funds target rate range of 0 to 25 basis points unchanged throughout all three rounds of Quantitative Easing, the last of which officially ended in October 2014. The first change in the target range, and thus the first test of the Fed’s new approach to interest-rate targeting, came more than a year later, in mid December 2015, when the Fed announced a new rate range of 25 to 50 basis points. Another year passed before the Fed hiked the range for a second time, to 50 to 75 basis points, where it remains as of this writing.

Overnight Reverse Repos

The upper bound of the fed funds target range is, as we’ve seen, simply equal to the interest rate the Fed pays on banks excess reserve balances; so to raise that the Federal Reserve Board has simply to approve and announce a new rate. Raising the lower bound above zero is another matter altogether. To do this, the Fed introduced still another novel monetary control instrument, consisting of a revamped Overnight Reverse Repo (ON-RRP) program it had been tinkering with since the spring of 2014.

As I explained in Part 3 of this primer, repos, or repurchase agreements, had long been part of the Fed’s open-market operations. But prior to the crisis the Fed made such agreements only with the small number of Primary Dealers it usually dealt with, and for the purpose of making such temporary adjustments to the supply of bank reserves as were needed to achieve its fed funds target. To temporarily increase banks’ reserves, it might agree to purchase securities from one or more dealers, under the condition that they repurchase them the next day. To temporarily withdraw reserves from the banking system, it could instead resort to overnight “reverse” repos, selling securities to one or more dealers, while promising to repurchase the same securities the next day.

The post-crisis ON-RRP differed both in its scope and in its purpose. Instead of being limited to a score or so of Primary Dealers, it involved a much larger number of counterparties, including Fannie and Freddie, four of the nation’s eleven Federal Home Loan Banks, and 94 money market mutual funds. For the purpose of implementing the Fed’s new system of monetary control, however, it was the inclusion of the GSEs that mattered. For those institutions now had a new way to earn interest on their idle Federal Reserve deposit balances. Instead of lending them to banks overnight, in return for some share of the interest banks were earning on their own Fed balances, they could instead take part in the Fed’s overnight securities sales, profiting on the difference between the Fed’s sale price and the price it agreed to pay to repurchase the securities a day latter. So long as they could take part in the Fed’s overnight repos, the GSEs had no reason to lend funds to banks overnight for less than the repos’ implicit interest return. The Fed’s new repo facility thus allowed it to set an above-zero lower bound on its federal funds rate target range, starting with the 25 basis point lower bound it announced in December 2015, which it doubled in December 2016.

So there you have it. Although we continue, as in the past, to identify monetary tightening or loosening with the Fed’s determination to raise or lower “interest rates,” since 2008 both the interest rates involved, and the Fed’s way of altering them, have changed dramatically. Instead of endeavoring to influence a market-determined federal funds rate by reducing or increasing the supply of bank reserves, the Fed now adjusts a pair of rates determined solely by its own administrative decrees, while conducting open-market operations without any particular reference to these rate adjustments. Sometimes, a wise Frenchman might say, the more things stay the same, the more they change.