The Miami-Dade Police Department (MDPD) is scrapping plans to test persistent aerial surveillance technology following criticism from privacy advocates. This kind of technology has prompted privacy concerns in others cities, with Baltimore being perhaps the most notable. One of the best-known aerial surveillance companies allows users to keep a roughly 25 square mile area under surveillance and comes with “Google Earth with TiVo” capability, The news from Miami-Dade county. while reassuring, underlines a number of issues concerning federalism, privacy, and transparency that lawmakers must tackle as aerial surveillance tools improve and proliferate.

MDPD Director Juan Perez was set to ask county commissioners to retroactively approve a grant application to the Department of Justice for the aerial surveillance testing. The fact that MDPD was seeking federal money for the surveillance equipment reminds us that federal involvement in state and local policing should be strictly limited.

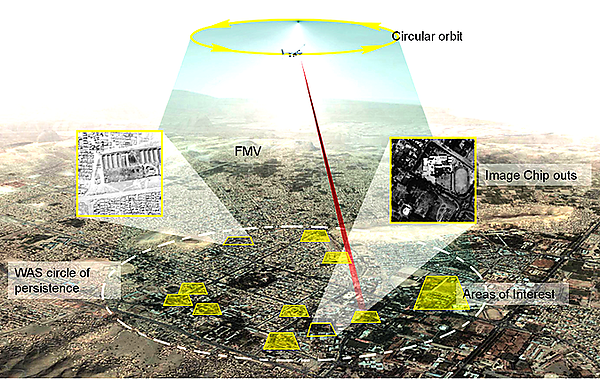

The aptly-named Persistent Surveillance Systems (PSS), the Ohio-based company that made the sensor system deployed in Baltimore, uses technology originally designed for military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Military equipment has an unfortunate tendency to make its way from foreign battlefields into the hands of domestic law enforcement, as my colleagues have been outlining for years. This is a trend that ought to be strongly resisted.

It’s not clear if the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs would have approved MDPD’s grant application, but given the current attorney general’s record on civil liberties, as well as the president’s own enthusiasm for aerial surveillance, we shouldn’t be surprised if similar grants are approved during the Trump administration.

In the most recent edition of the Cato Handbook for Policymakers my colleague Adam Bates and I argue that federal grants for drones, cell-site simulators, and body cameras should be dependent on a number of privacy, transparency, and accountability policies. Among the privacy policies we outline are a warrant requirement for police use of drones. Both of us fear the kind of persistent snooping made possible by aerial surveillance technology, whether it is attached to manned or unmanned aircraft.

Thanks to a handful of Supreme Court cases from the 1980s, police do not need a warrant to observe your property from the air. PSS and Baltimore police relied on these cases when issuing a memorandum supporting the use of persistent aerial surveillance, which reads in part:

Here, like in Ciraolo, Dow Chemical, and Riley, the photographs taken from a manned aircraft flying within publicly navigable airspace do not constitute a search, and do not run afoul of the Constitution. Particularly, the photographs were obtained by wide area airborne surveillance by manned aircraft operating in publicly navigable airspace at 3,000 to 12,000 feet altitude.

It is hard to see how PSS’ technology can be used with a warrant requirement in place given that it requires the continuous filming of a 25 square mile area. Perhaps some kind of safeguard could be implemented that requires law enforcement to have a court order before examining PSS’ data, thereby preventing police from going on fishing expeditions for crimes. Indeed, PSS’ own privacy policy already states that its sensors are only used to support crime investigations. But PSS’ privacy policy isn’t law, and until such policies are codified into law it’s probably best for PSS’ technology to be grounded and for the federal government not to fund state and local persistent aerial surveillance operations.

Aside from the privacy concerns associated this persistent aerial surveillance there are also worries related to transparency.

Members of the public deserve to know what surveillance technologies police are using and what data about their behavior are being collected. In Baltimore, PSS’ technology was flown over the city without elected officials (including the mayor), the state’s attorney, or members of the public being informed first. In Miami-Dade county, the mayor wasn’t aware of MDPD’s persistent aerial surveillance plans.

Local and state officials can take steps to address surveillance secrecy. For example, earlier this year California lawmakers introduced a bill that would require police to reveal information about the surveillance equipment they use to local officials. The bill would also require local officials to approve police using new surveillance technology.

Persistent aerial surveillance can be useful in investigating crimes, but we should be conscious of its costs as well as its benefits. Policies that protect privacy should be in place before snooping airplanes take to the sky, and the public as well as local officials should be informed about the surveillance tools police are using.