In a recent post, I announced the release of and provided excerpts from Cato’s latest health policy book, Medical Malpractice Litigation: How It Works, Why Tort Reform Hasn’t Helped, by Bernard S. Black, David A. Hyman, Myungho S. Paik, William M. Sage, and Charles Silver (foreword by former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle). Medical Malpractice Litigation compiles original research from states that capped damages in “med mal” cases to show that such reforms do not have the effects that physicians and other supporters claim. If anything, damage caps benefit physicians and insurance companies at the expense of patients and taxpayers.

Medical Malpractice Litigation is interesting for reasons broader than the med mal system itself. Many will find the book a paradox. Why would a libertarian think tank, whose goal is limited government, publish a book showing that government-limiting reforms harm consumers? Is it hypocritical that some libertarians find themselves on the same side of this health care issue as Democrats, who favor extensive government involvement in health care?

The answer to these questions lies in the fact that Medical Malpractice Litigation highlights an interesting area of health policy where government redistribution of wealth is consistent with libertarian principles; where Republicans have enacted reforms that do indeed limit government, but more than is optimal; and where libertarian principles therefore counsel expanding government redistribution.

Curious yet? Good.

A Libertarian Perspective on Medical Malpractice

Libertarians generally support the existence of the med mal system, and the tort system more broadly, because redistributing wealth from tortfeasors to their victims protects liberty. To the extent a physician or another tortfeasor can impose costs on you without your consent, you are not free. A med mal system protects freedom both by reducing how often physicians impose unwanted costs on their patients, and by preventing the cycle of violence that might otherwise follow when such episodes nevertheless occur.

Let’s take the second part first. A med mal system protects freedom and reduces the amount of violence in society by giving people who believe they have been victims of malpractice an alternative to a violent response. If the idea of patients or their families exacting street justice against negligent doctors seems far-fetched, consider that in China, such street justice is basically a business:

In China, [a] particular form of violence, of criminal gangs specifically targeting hospitals is called Yinao, which literally means “healthcare disturbance.” The purpose is to intimidate hospital administration into paying compensation for perceived malpractice…Gangs consist largely of unemployed people with a designated leader and are hired by patients or their families with the express purpose of extorting money. Professional Yinao gang members advertise on bathroom walls and in outpatient departments and travel daily between the hospitals to locate “business opportunities.”

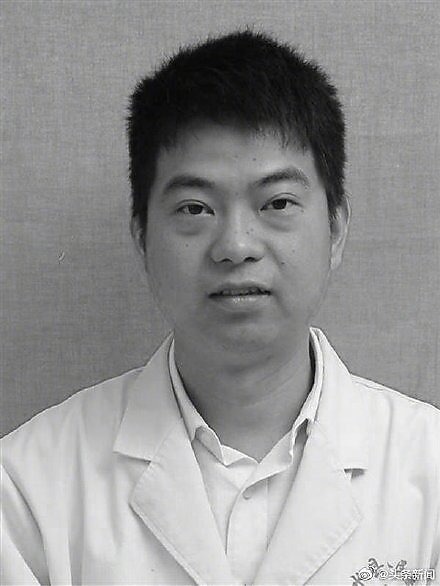

Whether the actions of organized groups or angry individuals, yinao attacks on Chinese doctors and other clinicians are often fatal. The photo at right shows 38-year-old Hy Shuyun, a cardiologist in Jiangxi Province who died in January 2021 after an assailant stabbed him multiple times at the hospital where he worked. Over a recent 10-year period:

From 2009 to 2018, 24 medical personnel died and 362 were injured in 295 reported cases, according to a 2019 report by the School of the Journalism and Communication of Renmin University of China.

Individual incidents of such violence are gruesome:

Official data from China’s Ministry of Health reported “9,831 ‘grave incidents’ of medical disputes in 2006, with 5,519 medical staff injured and 200 million yuan (over 29 million dollars) in property damage…In September of 2011, a Beijing calligrapher became so dissatisfied with his throat-cancer treatment that he stabbed his doctor seventeen times. In Wenling City in 2013, a patient attacked three doctors, killing one of them. In February 2014, patients “paralyzed a nurse in Nanjing, cut the throat of a doctor in Hebei, and beat a Heilongjiang doctor to death with a lead pipe.” [In 2016,] in Guangdong Province, a knife-wielding patient chased a doctor down the halls of the hospital, slashing her arms and legs…The Chinese Hospital Management Association found that [by 2012,] “Chinese hospitals were reporting an average of twenty-seven attacks a year, per hospital”…But why are assaults on doctors so prevalent in China specifically?

To answer this question, many legal experts point to the lack of a unified medical negligence legal system.

A functioning medical malpractice liability system gives those who believe they have been victims of malpractice—whether the patient or family members—a more peaceful way to seek redress. To the extent it holds negligent physicians and other providers accountable for the injuries they cause, it reduces the incentives for malpractice victims to resort to violence. Since a med mal system employs less coercion than violent mobs (see below) it protects freedom by reducing the level of violence in society.

A medical malpractice liability system further protects freedom by creating incentives for physicians to avoid imposing unwanted costs on their patients. To the extent physicians know they will bear the cost of the additional medical care, lost wages, or pain and suffering that their negligence might cause, they will take greater care to avoid imposing those costs. Along the way, patients also get better, safer medical care. Yinao also imposes the costs of negligent care on physicians. Since fact-finding is relatively perfunctory and death is rarely the socially optimal penalty for malpractice, however, yinao is likely to send physicians less precise signals about when and how to improve quality. Indeed, yinao may encourage providers to allocate resources toward personal protection instead of improving quality:

Predictable measures, such as the development of new guidelines with recommendations for duress alarms, scanning equipment, camera surveillance, and at least one security guard per 20 beds have been suggested. Drastic reactions include the employment of gangs to counter Yinao mobs, resulting in fights, while in other cases, nurses and doctors wear protective helmets and combat gear.

When a court orders a defendant to compensate the plaintiff, that order comes with a threat that the government will use coercive measures to force the physician to comply. But the fact that the med mal system employs coercion does not make it incompatible with libertarian principles, because such a system still involves less coercion than one where negligence victims feel their best option is violence.

The libertarian case for a med mal system, and torts more broadly, is thus similar to the libertarian case for police and national defense: the coercive measures that support these government activities are morally permissible to the extent they reduce the amount of violence in society. Like policing and national defense, the med mal system in the United States is far from the libertarian ideal. (One significant shortcoming: the med mal system currently does not allow patients and providers to devise their own liability rules, and instead forces everyone to live under rules that courts or legislatures impose.) But even a tort system that imperfectly compensates victims of medical malpractice is consistent with libertarian principles.

On Med Mal, Democrats Are More Libertarian Than Republicans

An interesting implication of this analysis is that med mal reform, like tort reform broadly, is an area where Democrats come closer to libertarian principles than Republicans do. In med mal debates, Democrats tend to take the side of plaintiffs—i.e., injured patients. They argue legislative limits on the ability to sue physicians for malpractice leave injured patients unable to afford the medical care they need. (Democrats also tend to collect political contributions from the plaintiffs’ attorneys who represent injured patients.) Republicans tend to take the side of defendants—i.e., physicians. They argue incorrect verdicts and runaway damage awards increase physicians’ costs of doing business and reduce access to care for everyone. They argue reforms such as damage caps would reduce those costs and expand patient access to care. (Republicans also tend to collect campaign contributions from physicians and those who represent physicians in med mal cases.)

One might think libertarian principles would give the edge to Republicans. Libertarians generally oppose government redistribution of wealth. The tort system is nothing if not a government program that redistributes wealth from one group to another.

On the contrary, libertarian principles suggest Democrats generally have the more liberty-friendly position. Libertarian principles counsel it is morally permissible for government to redistribute wealth from tortfeasors to their victims. Damage caps prevent such redistribution and thus force malpractice victims to bear costs they did not consent to bear. Examples abound:

- A patient in Indiana, who lobbied in favor of that state’s damage caps, later became a victim of malpractice. He suffered $5 million in injuries but the damage caps he once supported prevented him from collecting more than $500,000, leaving him with losses of at least $4.5 million.

- The Dr. Death podcast, which chronicles the tale of a Texas surgeon named Christopher Duntsch who maimed or killed dozens of patients, explains (season 1, episode 6) that many of Duntsch’s victims could not even find lawyers to represent them because Texas caps damages for pain and suffering (i.e., noneconomic damages) at $250,000. One of those the Dr. Death podcast interviews is Medical Malpractice Liability coauthor and Cato adjunct scholar Charlie Silver.

To the extent damage limit prevent redistribution from tortfeasors to their victims, they force malpractice victims to bear costs they did not consent to bear, reduce freedom, and reduce the quality of medical care.

Optimal Redistribution through the Med Mal System

Like police and national defense, a med mal system can fail to protect those it exists to protect, or employ excessive coercion, or do both simultaneously. It can fail to protect patients by being so costly that patients with valid claims cannot seek compensation. Or by ruling against plaintiffs with valid claims. Or by setting awards too low, so that patients do not receive full compensation. It can employ excessive force by ruling for plaintiffs when there was no malpractice, or by otherwise setting damages excessively high, each of which unjustifiably redistributes wealth from defendants to plaintiffs. The debate over med mal reform centers around how often the med mal system commits these various errors.

One area where the med mal system inevitably commits both types of error simultaneously is “the antiseptic calculus by which courts assign a monetary value to human suffering.” There will never be a perfect method of placing a monetary value on the costs negligent providers impose on their patients. Courts have traditionally left those decisions to juries on the theory that juries will come closer to a just or efficient settlement than other decision-making processes, such as the legislative process. The debate over damage caps centers around whether juries systematically set awards too high. Advocates of damage caps say yes; opponents say no.

Advocates of damage caps want legislatures to override the decisions juries make when it comes to awarding damages. If legislatures were able to approximate the actual costs negligent providers impose on their victims more accurately than juries, this would be appropriate. But legislatures are vulnerable to pressure from highly organized and well-funded special-interest groups in ways that juries are not. That raises the prospect that legislatures might move damages awards not so much toward optimality as in whichever direction the most powerful special-interest group prefers. Indeed, it has been pressure from powerful special-interest groups — physicians and other health care providers — that has led dozens of states to impose damage caps.

Medical Malpractice Litigation is an important book because it provides evidence that legislatures do not appear to be moving damages awards in the direction of optimality. Rather, damage caps just appear to be special-interest legislation that undermines the ability of the med mal system to protect patients and promote freedom.

A Really Interesting Area of Health Policy

Public-choice theory holds that organized interest groups will demand and secure from government special favors that enrich those groups at the expense of the majority. Libertarians seek to eliminate such subsidies and regulations because doing so would result in less government and more freedom.

The med mal system is an interesting public-choice case study where privilege-seeking and regulatory capture can lead to less government than is optimal, and where lifting or repealing mandatory damages caps would result in more government redistribution and more freedom.

When it comes to damages caps in med mal cases, Democrats therefore have the more libertarian position, while Republicans who pursue damage caps are limiting government at the expense of freedom.