A recent outbreak of measles at the Eloy Detention Center has raised some concerns over disease and immigration. The disease was carried in by an immigrant who was detained, allowing it to spread among some of the guards who were not vaccinated. The Detention Center has since claimed that it vaccinates all migrants who are there and is working on getting all of its employees vaccinated. Regardless, how much should we worry about measles brought in by unvaccinated immigrants? Very little.

First, measles vaccines are highly effective at containing the disease. There are two primary measles vaccinations. The first is the MCV‑1 which should be administered to children between the ages of nine months and one year. MCV‑2 vaccinations are administered later, at the age of 15 to 18 months in countries where measles actively spreads. In countries with very few cases of measles, like the United States, the MCV‑2 is optional and is not typically administered until the child begins schooling.

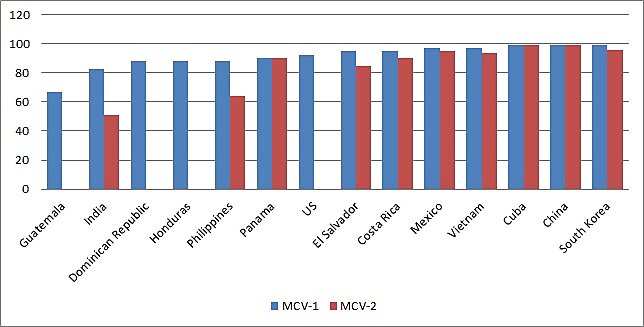

Second, the nations that send immigrants tend to have high vaccination rates. The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF report the measles vaccination rates for most countries. Figure 1 shows those rates for 2014 by major immigrant sending country. For the MCV‑1, the United States is in the middle of the pack with 92 percent coverage and no data reported for MCV‑2. The countries of El Salvador, Costa Rica, Mexico, Vietnam, Cuba, China, and South Korea all have higher MCV‑1 vaccination rates than in the United States.

Six countries do have lower vaccination rates than the United States although Indian and Filipino immigrants are more highly educated than their former countrymen, indicating that their vaccination rates are higher before beginning the immigration process. Furthermore, legal immigrants must show they are vaccinated, meaning that the relatively low vaccination rates in some of those countries of origin don’t reflect vaccination rates among the population of immigrants here.

However, the U.S. government’s vaccination requirements indicate that unauthorized immigrants are possibly less likely to be immunized than legal immigrants. One way to increase vaccination rates among all immigrants, legal and illegal, would be to make green cards available to immigrants who are more likely to come unlawfully, thus guaranteeing that they are vaccinated.

Figure 1

MCV‑1 Vaccination Rates, 2014

Source: WHO-UNICEF

In a more worrying trend, vaccine refusal rates are up among the native-born Americans in wealthy enclaves in California.