Ridley is the author of numerous best-selling (and excellent) books on science and society. We especially like his 2010 book, The Rational Optimist, How Prosperity Evolves, for which he won the Manhattan Institute’s prestigious Hayek prize. In that work, Ridley draws on both the biological theory of evolution, and the theories of specialization and trade made famous by Adam Smith, to argue that human societies possess a natural tendency to become both more economically specialized and more prosperous.

The Evolution of Everything elaborates on the same theme, by showing how social progress mainly happens, not in response to politicians’ mandates, but because of the free activity of everyday people. Its chapters illustrate Ridley’s “bottom up” view of history, which he contrasts with the usual emphasis upon history as shaped by bureaucrats, politicians, and armies.

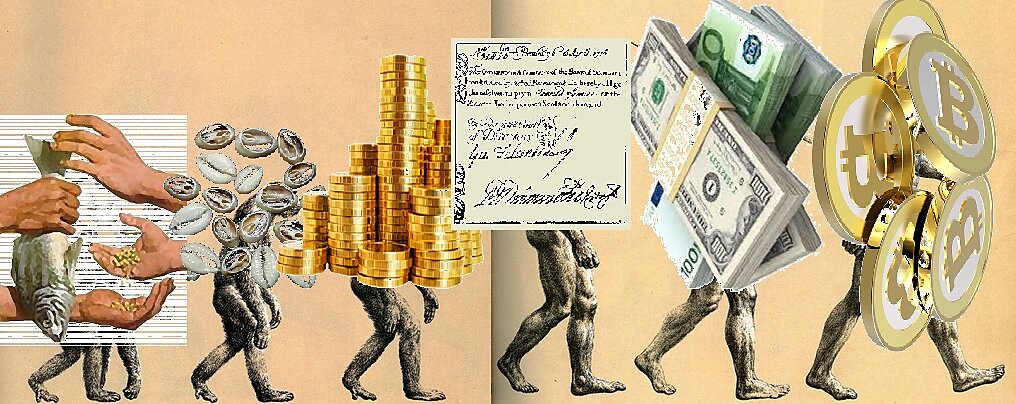

Our favorite chapter of Ridley’s new book is—surprise, surprise!—the one on “The Evolution of Money,” in which he argues that spontaneously-developed monetary systems tend to be more stable, more egalitarian, and more prosperity-enhancing, than ones that are deliberately designed and centrally managed. As evidence he refers to George Selgin’s study of Birmingham’s private coinmakers, as well as Larry White’s work on the Scottish free banking system.

Of Birmingham’s coiners, Matt writes:

Birmingham businessmen had privatized the penny. Their coins were a vast improvement on the Royal Mint’s rivals. This despite the fact that the new coins had been designed from scratch in just a few years, and had no legal protection against fraud, unlike the Mint’s coins. Unprotected by monopoly privilege, the commercial coiners had not only to be cost-effective, but to attract the best engravers and strikers, and had to design their coins so they would be hard to imitate. [p. 279]

Of Scotland’s 1716–1844 free-banking era, he adds:

Scotland experienced unparalleled monetary stability, pioneering financial innovation amid rapid economic growth as it caught up with England. It had a self-regulating monetary system, which worked as well as any other monetary system at any other time or place. Indeed it was so popular Scots rushed to praise and defend their banks — a phenomenon largely unheard of in history. [p. 281]

Such episodes of spontaneous monetary order stand in stark contrast to recent experience, in which government guarantees and other misguided programs led to boom and bust — despite (and often with the connivance of) layer upon layer of regulatory oversight. Ultimately, writes Ridley,

the explosion in sub-prime lending was a thoroughly top-down, political project, mandated by Congress, implemented by government sponsored enterprises, enforced by the law, encouraged by the president and monitored by pressure groups. Remember this when you hear people blame the free market for the excesses of the sub-prime bubble. [p. 291]

But don’t settle for these little snippets. Read the whole book. Better still: get yourself a signed copy, and listen to the man himself, here at Cato. That’s tomorrow between noon and 1:30. You can sign up for the event here. Those who can’t make it can listen to the livestream here.

Disclaimer

This post was originally published at Alt‑M.org. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Cato Institute. Any views or opinions are not intended to malign, defame, or insult any group, club, organization, company, or individual.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The Cato Institute makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. Cato Institute, as a publisher of this article, shall not be liable for any misrepresentations, errors or omissions in this content nor for the unavailability of this information. By reading this article and/or using the content, you agree that Cato Institute shall not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this content.