In reviewing the Green New Deal, the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip says, “Because the private market has no incentive to reduce carbon emissions, government intervention is necessary.”

No incentive? That is obviously incorrect.

In competitive markets, there is relentless pressure on businesses to reduce costs, including the costs of energy and other resource inputs. The production and consumption of just about everything is far more energy efficient today than in past decades because of businesses striving for profits and consumers striving to save money.

Ip’s claim is refuted by another story in the WSJ today regarding airline fuel efficiency.

The industry’s move toward reducing carbon emissions has been slow. Improvements in new airplanes have reduced emissions significantly, but with more airplanes flying more people, overall tonnage of carbon emitted by commercial aviation has been inching higher, not lower, in recent years.

The statement “has been slow” is unfair, as the rest of the article indicates:

Today’s new planes are about 20% more fuel-efficient than the previous generation from the 1990s, Airbus and Boeing say, and 70% more fuel-efficient than early jets of the 1960s. On a per-passenger basis, fuel economy has improved: Airlines now fly with fewer empty seats and more seats packed into each jet. But most of the improvement has come from manufacturers. Engines get more thrust out of the fuel they burn, planes are much lighter today and aerodynamics has reduced drag.

The drive by airlines to save money and keep ticket prices down has led them to push manufacturers to design ever more efficient airplane and engine configurations.

The WSJ article includes a chart showing total fuel consumption by U.S. airlines has fallen from about 18 billion gallons in 2000 to about 17 billion in 2017. What the article does not report is that total U.S. air passenger-miles increased from 700 billion in 2000 to more than 950 billion by 2017.

In aviation, as in many industries, rising consumer demand puts upward pressure on emissions, but businesses and markets have strongly countered that pressure with an endless stream of innovations that have reduced fuel use and thus carbon emissions.

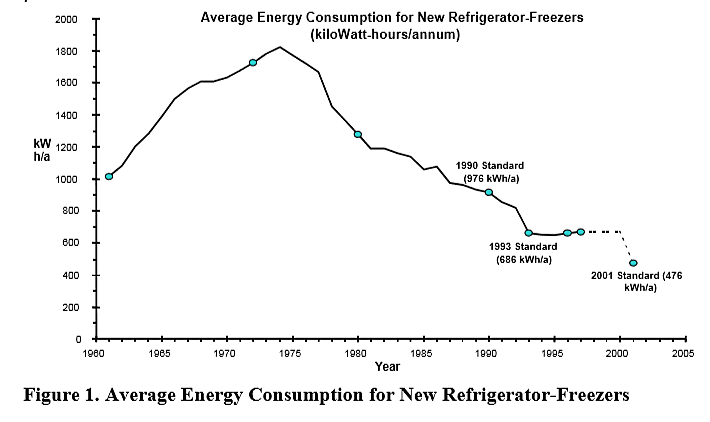

Here is another example of the business drive for efficiency from a Cato study on household appliances. With rising energy prices in the 1970s, markets dramatically increased the energy efficiency of refrigerators even before federal efficiency standards were put in place in 1990. New fridge energy consumption plunged from more than 1,800 kwh a year in 1975 to 976 kwh in 1990—driven by consumers wanting to save money and producers innovating in competitive markets.

Contrary to Greg Ip, private markets have strong incentives to reduce energy use and thus reduce carbon emissions.

(A cleaner copy of the chart is in this paper).