President-Elect Trump’s selection of philanthropist and long-time school choice advocate Betsy DeVos for Secretary of Education has the public education establishment and its allies in panic mode. American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten tweeted “Trump has chosen the most ideological, anti-public ed nominee since the creation of the Dept of Education.” Over at Slate, Dana Goldstein frets that “Trump could gut public education”—even though federal dollars account for less than 10 percent of district school funding nationwide. The New York Times has also run series of hand-wringing pieces about what the Trump administration has in store for our nation’s education system.

At the center of the panic over Trump’s nomination of DeVos is their support for school choice. Although light on details, Trump has pledged to devote $20 billion to a federal voucher program. As is so often the case, the most vocal opponents of federal school choice are right for the wrong reasons. Not only does the federal government lack constitutional jurisdiction (outside of Washington, D.C., military installations, and tribal lands), but a federal voucher program poses a danger to school choice efforts nationwide because a less-friendly future administration could attach regulations that undermine choice policies. Such regulations are always a threat to the effectiveness of school choice policies, but when a particular state adopts harmful regulations, the negative effects are localized. Louisiana’s folly does not affect Florida. Not so with a national voucher program. Moreover, harmful regulations are easier to fight at the state level than at the federal level, where the exercise of “pen and phone” executive authority is increasingly (and unfortunately) the norm.

Many of Trump’s critics have not addressed very real federalism concerns, but have instead used the DeVos appointment to attack school choice generally, particularly its more free-market forms.

In a New York Times blog, Kevin Carey of the left-wing New America Foundation writes:

Ms. Devos [sic] will also be hamstrung by the fact that her deregulated school choice philosophy has not been considered a resounding success. In her home state, Detroit’s laissez-faire choice policies have led to a wild west of cutthroat competition and poor academic results. While there is substantial academic literature on school vouchers and while debates continue between opposing camps of researchers, it’s safe to say that vouchers have not produced the kind of large improvements in academic achievement that market-oriented reformers originally promised.

In a Times op-ed, Tulane Professor Douglas Harris echoed these critiques, claiming that “even charter advocates acknowledge” that Detroit’s charter school system—which DeVos supposedly “devised […] to run like the Wild West”—is “the biggest school reform disaster in the country.”

Consider this: Detroit is one of many cities in the country that participates in an objective and rigorous test of student academic skills, called the National Assessment of Educational Progress [NAEP]. The other cities participating in the urban version of this test, including Baltimore, Cleveland and Memphis, are widely considered to be among the lowest-performing school districts in the country.

Detroit is not only the lowest in this group of lowest-performing districts on the math and reading scores, it is the lowest by far. One well-regarded study found that Detroit’s charter schools performed at about the same dismal level as its traditional public schools. The situation is so bad that national philanthropists interested in school reform refuse to work in Detroit. As someone who has studied the city’s schools and used to work there, I am saddened by all this.

Likewise, Harvard Professor Paul Reville decried that “in places like Michigan and Arizona where the approach to opening up choice has been a Wild West version of an unregulated free market, the results have been highly disappointing, giving school choice a bad name.”

Charter schools in Michigan and Arizona may be subject to fewer government regulations than in other states, but it’s absurd to describe the sectors as “laissez-faire” or “an unregulated free market.” For example, charter school regulations in both states, as elsewhere, limit the ability of charter schools to set their own mission (e.g., they must be secular), mandate that they administer the state standardized test, forbid them from setting their own admissions standards, forbid them from charging tuition, limit who can teach in the schools, limit the growth of the number of schools, and so on.

“Laissez-faire” indeed!

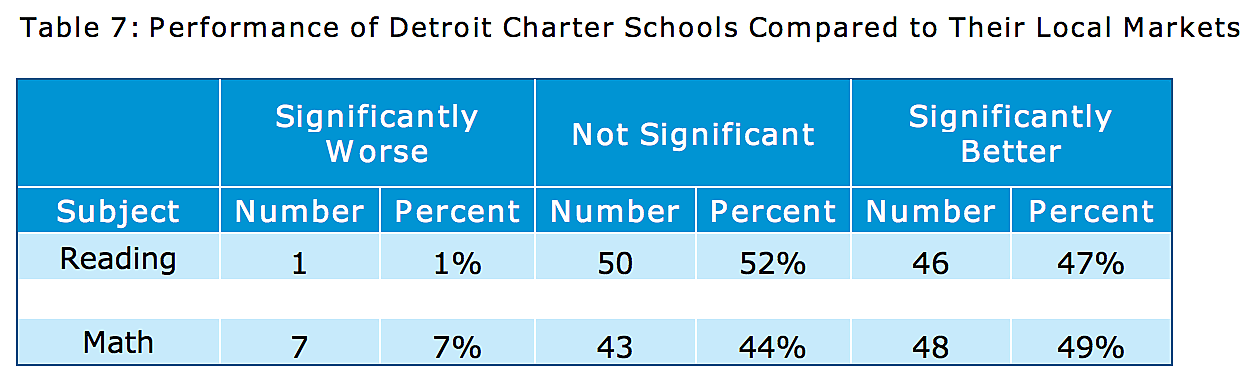

And although Michigan’s results are far from stellar, they’re also not the “disaster” that Harris depicts. Indeed, Harris links to the 2013 CREDO report, which found that, on average, Detroit’s charter schools outperformed the district schools that their students would otherwise have attended. Indeed, nearly half of Detroit’s charter schools outperformed the city’s traditional district schools in reading and math scores, while only one percent of charter schools performed worse in reading and only seven percent performed worse in math.

Source: CREDO’s 2013 report on charter schools (page 44).

CREDO’s 2015 report even called Detroit’s charter sector “a model to other communities.” I’d say that’s overstating it. Nevertheless, while Detroit’s district schools are so bad that it’s not a very high bar, Detroit does show how even a significantly regulated system of school choice can outperform the government’s system of district schools. Using the CREDO study to knock Detroit’s charter sector is, to borrow a phrase from Harris, “a triumph of ideology over evidence.”

And since Harris mentioned the NAEP, let’s see how Arizona’s “Wild West” charter sector performs. As education analyst Matthew Ladner has detailed, Arizona’s charter sector not only outperformed the state average for gains between the 2011 4th-grade and 2015 8th-grade NAEP tests for math and language arts, but they beat the statewide average gains for every single state. The Arizona charter sector’s gains between the 2009 and 2015 NAEP science tests were at least double the statewide average gains everywhere else.

Source: Matthew Ladner.

A word of caution is in order. These comparisons don’t account for differences in demographics among states nor changes in demographics over time. The raw NAEP results cannot tell us whether a particular policy caused any improvement or decline in the scores. Moreover, as Ladner notes, it’s possible to have significant gains while simultaneously doing poorly overall. The bowler whose average score improves from a 25 to a 50 might earn the “Most Improved” trophy while still being the worst bowler in the league. That said, after controlling for demographics, Arizona’s math and language arts scores are above average (13th nationwide). Although we don’t have adjusted scores for Arizona’s charter sector, they are likely even better. Moreover, even using raw scores, Arizona charter students perform about as well as Massachusetts students on the 2015 8th grade NAEP science test. For that matter, Arizona’s charter schools topped the list for college attendance among Arizona’s 2015 graduates.

If Harris believes that supposed lack of regulation in Detroit’s charter sector (at least as compared to charter school regulations in other states) accounts for their poor performance on the NAEP, how does he explain the Arizona results?

Indeed, even without heavy top-down oversight, Arizona manages to close down poorly performing charter schools fairly quickly through a rather innovative method called “parental choice.” The average closed charter operated for only four years and had an average of only 62 students enrolled in their final year. As Ladner explains, parents put most of those charters out of business before the regulatory apparatus got around to it:

Arizona parents seem extremely adept at putting down charter schools with extreme prejudice. Arizona parents detonate far more schools on the launching pad compared to the number we see bumbling ineffectively through the term of their charter to be shut by authorities (or to give up the ghost in year 14 in an ambiguous fashion). Both of these things happen, but the former happens with much greater regularity than the latter. Having a vibrant system of open enrollment, charter schools and some private school choice means that Arizona parents can take the view that life is too short have your child enrolled in an ineffective institution.

The critics’ read of the evidence on voucher programs also leaves much to be desired. Harris points only to research on statewide voucher programs in Louisiana and Ohio that found negative impacts, but he ignores the near-consensus of more than a dozen random-assignment studies that found modest positive impacts on student performance on tests as well as on high school graduation and college matriculation. Outside of Louisiana’s heavily regulated voucher program, none were found to produce a negative impact and only one found no discernible impact. (The Ohio study was not random-assignment and its comparison group may have been severely compromised by the study’s design.) Moreover, nearly every study on the impact of private school choice policies on district school performance found a positive impact, including in Louisiana and Ohio. The one exception was Washington, D.C., where the voucher funds come from a separate source and therefore a decrease in district school enrollment does not affect their funding.

On the whole thus far, private school choice programs have been an improvement over the status quo. Nevertheless, Carey is only half right when he writes that “vouchers have not produced the kind of large improvements in academic achievement that market-oriented reformers originally promised” because no state has yet adopted the sort of large-scale, lightly regulated, universal voucher system that market-oriented reformers like Milton Friedman called for. Instead, most voucher programs are limited in scale and eligibility and subject to numerous regulations. They’re designed, essentially, to fill empty seats rather than to revolutionize the way education is delivered. Small-scale choice programs should be expected to deliver positive but small-scale results, and that is what the research has found.

Advocates of large-scale private school choice programs should be careful not to over-promise, but critics of market-oriented educational choice policies should also be careful not to cherry pick or to make claims that the research literature does not support. Outside heavily regulated environments, private school choice policies have a consistently positive track record. What we should be able to agree about is that the positive track record of state-level school choice policies does not imply that Congress should enact a federal voucher program.