Last week, President Trump issued a new executive order (EO) that restarts the refugee system with new “enhanced” vetting procedures. The new procedures will subject the follow-on family members of refugees to about the same level of vetting as the original refugee sponsors who have already been settled in the United States. This extension of the current refugee vetting system will cover about 2,500 additional follow-on refugees per year. The EO also forward-deploys specially trained Fraud Detection and National Security officers at refugee processing locations to help identify potential fraud, national security, and public safety issues earlier in the screening process. Additional actions of the EO are enhanced questions to identify fraud and other inadmissible characteristics as well as upgrades to databases to detect potential fraud or changes in refugee information at different interview stages. The EO also directs the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the Director of National Intelligence, to review and reform refugee vetting procedures on an annual basis.

The EO justifies these new measures by stating that, “It is the policy of the United States to protect its people from terrorist attacks and other public-safety threats … Those procedures enhance our ability to detect foreign nationals who might commit, aid, or support acts of terrorism, or otherwise pose a threat to the national security or public safety of the United States, and they bolster our efforts to prevent such individuals from entering the country.”

All in all, these new vetting procedures are modest additions to the already intensive refugee screening that occurs. If these new enhanced screening procedures are supposed to be the “extreme vetting” that President Trump proposed then they show just how extreme and secure the refugee program already was. Furthermore, they are unnecessary.

Terrorists by Refugee-Restricted Countries

The EO also places additional scrutiny on refugees from Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Mali, North Korea, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Those eleven nations represent supposed security threats identified on the Security Advisory Opinion (SAO) – a government list of nations established in the 1990s whose nationals are supposed to be more closely scrutinized for particular national security threats. The government has updated and expanded the SAO criteria as well as the nations on the list multiple times since 9/11.

The government may have an excellent rationale for designating nationals from these eleven countries as serious threats that require more refugee vetting but those reasons and the evidence supporting them are not available for the public to examine. Publicly available information points to a small refugee threat from refugees from these nations that does not justify additional screening. Since 1975, zero Americans have been murdered on U.S. soil in a terror attack committed by refugees from any of the eleven countries.

In a departure from previous EOs, nationals from one of these countries have killed people on U.S. soil in terrorist attacks but none of the attackers have been refugees. Four terrorists from Egypt did manage to kill a total of 162 people in attacks on U.S. soil (Table 1). They were Mohammad Atta who participated in the 9/11 attacks, Hesham Mohamed Hadayet who murdered two in a shooting at LAX in 2002, and El Sayyid Nosair and Mahmud Abouhalima who both were involved in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. All four Egyptians entered on tourist visas. Only six Iranians (four of them in the 1970s), six Sudanese (all six in 1993 or before), two Iraqis, two Somalis, and one Yemeni carried out attacks on U.S. soil or were convicted of doing so (Table 1). The two Iraqis did enter as refugees although one might not be a terrorist and the other was arrested in a sting operation. The rest entered on student visas, tourist visas, green cards, or under the visa waiver program as they had dual Canadian-Iranian citizenship.

Table 1

Murders and Number of Terrorists by Country of Origin, 1975–2015

| Country | Terrorists | Murders | Percent of All Terrorists | Percent of All Murders in Terror Attacks |

| Egypt |

11 |

162 |

7.1% |

5.4% |

| Iran |

6 |

0 |

3.9% |

0.0% |

| Iraq |

2 |

0 |

1.3% |

0.0% |

| Libya |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Mali |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| North Korea |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Somalia |

2 |

0 |

1.3% |

0.0% |

| South Sudan |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Sudan |

6 |

0 |

3.9% |

0.0% |

| Syria |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Yemen |

1 |

0 |

0.6% |

0.0% |

| All |

28 |

162 |

18.2% |

5.4% |

John Mueller, ed., Terrorism Since 9/11: The American Cases; RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents; National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism Global Terrorism Database; Center on National Security; Charles Kurzman, “Spreadsheet of Muslim-American Terrorism Cases from 9/11 through the End of 2015,” University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill; Department of Justice; Federal Bureau of Investigation; New America Foundation; Mother Jones; Senator Jeff Sessions; Various news sources; Court documents.

De Facto Restrictions on Muslim Refugees

From January 1, 2002 through October 20, 2017, a total of 921,760 refugees entered the United States. A total of 338,831 of them, or 37 percent, came from the 11 countries that are the subject of the new restrictions. However, 76 percent of all Muslim refugees who entered the United States during that time came from those 11 countries that will have new restrictions placed on them. President Trump said on at least a dozen occasions that his proposed travel bans and restrictions were Muslim bans but his defenders always correctly pointed out that not all Muslim-majority countries made the list. It looks like those nations that sent more than three-quarters of all Muslim refugees did make the list for extra scrutiny though.

Crime by Country of Origin

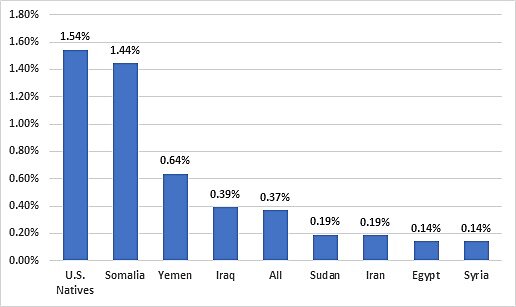

The administration has broadened its justification for these EOs from just terrorist attacks to include “other public-safety threats.” As far as we can tell, that specifically refers to crime rates. One common way to measure the criminality of a particular population is that population’s incarceration rates relative to other groups. Although not perfect, this is one of a handful of measures available given the low-quality of American crime data. The incarceration rates for immigrants from the eleven countries on the new list are all below that of native-born Americans except for Somalis who are within the statistical margin of error (which means that Somalis and natives have about the same incarceration rate). Syrian-born immigrants, the most feared in this debate over immigrant vetting, have the lowest incarceration rate of any national group (Figure 1). The rate for all 11 countries is 0.37 percent, about one-fourth that of the native-born rate of 1.54 percent.

Figure 1

Incarceration Rates by Country of Birth, Ages 18–54

Source: Author’s analysis of the 2015 1‑year American Community Survey data. Special thanks to Michelangelo Landgrave for assembling these numbers.

Note: The numbers are too small to show for Libya, Mali, and North Korea. South Sudan is not separated in the American Community Survey data.

The national security justifications for the choice of countries in the first, second, and third EOs rang hollow. Those countries initially selected had not sent any deadly terrorists to the United States since 1975. The government supposedly selected them based on a complex review of security and vetting vulnerabilities but the selection still makes no sense and is likely basic on executive whim. Now, the government has widened its justification from terrorism and national security to the nebulous “public safety of the United States” – a justification that can only mean crime. Just as the national security justification for additional vetting rang hollow, so does the “public-safety threat” justification.

Conclusion

The enhanced vetting procedures for refugees are modest extensions of current vetting procedures. Before President Trump took office, refugee vetting was already extreme and difficult to further enhance. The eleven countries singled out for intensive new refugee scrutiny make little sense from a national security perspective and even less sense if the goal is to secure the public safety of Americans. No refugee from any of those nations has murdered an American in a terrorist attack on U.S. soil and their incarceration rates, except for Somalis, are all well below those of native-born Americans.