Portugal is “on edge of abyss” reads the headline of a Reuters story last week. Despite receiving a $104.5 billion bailout last year from the EU and the IMF, the country’s economy continues to shrink as unemployment soars and uncertainty about its permanence in the euro remains steady. Just like Greece, Portugal might need a second bailout soon.

As has been the case elsewhere, some pundits claim that austerity is in part responsible for Portugal’s current economic malaise. Even the IMF has said that deficit targeting “may not be the best policy” if the country falls deeper into recession. The question then is what we understand by “austerity.”

First, it is important to point out that Portugal got in trouble for having a government that spent too much over a long time. Back in 2001 the country was the first to breach the 3% of GDP deficit ceiling agreed to as part of the Stability and Growth Pact. Since then, it ran significant budget deficits, and in 2009, as a reaction to the global downturn, Portugal implemented a massive stimulus package that shot its deficit to 9.4% of GDP. (It is worth noting that the stimulus didn’t work, unemployment went up from 9.5% in 2009 to 14.9% now).

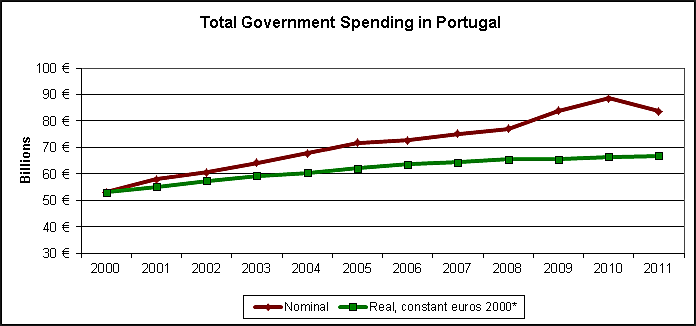

* Using GDP deflator.

Source: European Commission, Economic and Financial Affairs.

Spending in nominal terms increased on average by 5.6% every year from 2000 to 2010. As we can see in the graph, it accelerated in 2009 as the Socialist government of José Socrates tried to fend off the global recession with a Keynesian-style stimulus. It was not until 2011 that the new government of Pedro Passos Coelho began implementing spending cuts, which reduced overall spending by 5.5% from the previous year. Still, government spending in 2011 was at the same level of 2009. In real terms, there has been no decline in spending levels.

As a percentage of the size of the economy, total government spending in Portugal in 2011 stood at 45.2% of GDP, just a whisker down from its 2009 peak of 45.8%.

Early on Socrates tried to tame the deficit with tax increases. He raised the VAT rate from 19% to 21%. As part of last year’s the bailout agreement, Passos Coelho raised the VAT further to 23%, one of the highest rates in Europe. His government also introduced changes in the income tax: some rebates were scrapped; a surtax of 1.5% and 2.5% was introduced for middle and high income earners, respectively. A special corporate tax rate of 12.5% for small businesses was raised to 20%, and a surtax of 3% and 5% was created for medium and big companies, respectively. There were also tax increases on alcohol, fuel and tobacco.

The evidence suggests that even though in the last year there have been measurable spending cuts in Portugal (and I’m sure that people there are feeling the pinch from those cuts), tax increases constitute a significant chunk of the austerity policies implemented in that country.