Let’s hope President Trump’s health is as sound as he says it is and he’s well on the road to recovery. He certainly seems… chipper, at any rate. Still, you’d be a fool to take such professions on faith—not just because of the non-stop frenzy of dissembling and double talk we’ve seen since Friday, when the president revealed he was COVID-positive—but because of the long history of official lies about presidents’ health.

When I saw the headline “Medical Spin in Past Undermines Trust” in Sunday’s New York Times, I thought they’d go into some of that history. But the article’s mostly about past dissembling by this president’s doctors about this president’s health. Fair enough, but a longer view gives us still more reason to verify, instead of trust, official pronouncements about the state of any president’s health.

The best-known story is probably Woodrow Wilson’s massive stroke in October 1919, which left him bedridden and almost wholly incapacitated for the remainder of his term. His wife Edith essentially served as acting president, “shield[ing] Woodrow from interlopers and embark[ing] on a bedside government that essentially excluded Wilson’s staff, the Cabinet and the Congress.” But, as historian Robert Dallek recounts in his 2010 article “Presidential Fitness and Presidential Lies,” examples are legion. FDR managed to keep the public mostly in the dark about his partial paralysis from polio, aided by camera-snatching Secret Service agents who wouldn’t allow photos of the president in a wheelchair. While pursuing a fourth term in 1944, Roosevelt was “suffering from an enlarged heart and severe hypertension that threatened his life, [and] experienced significant weight loss, headaches, fatigue, and an inability to concentrate for sustained periods of time.” He died 82 days after inauguration. “In running for reelection under these circumstances,” Dallek writes, “FDR committed a terrible ethical breach.”

John F. Kennedy’s aura of vitality and “vigah” depended on deliberate lies about his massive health problems, including the adrenal-gland disorder Addison’s disease, for which he required regular steroid treatments. In 2013, after examining a raft of newly released Kennedy papers, Dallek reported that

“during his presidency—and in particular during times of stress, such as the Bay of Pigs fiasco, in April of 1961, and the Cuban missile crisis, in October of 1962—Kennedy was taking an extraordinary variety of medications: steroids for his Addison’s disease; painkillers for his back; anti-spasmodics for his colitis; antibiotics for urinary-tract infections; antihistamines for allergies; and, on at least one occasion, an anti-psychotic (though only for two days) for a severe mood change that Jackie Kennedy believed had been brought on by the antihistamines.”

Kennedy’s regimen also included a potent cocktail of painkillers and amphetamines regularly administered by celebrity physician Max “Dr. Feelgood” Jacobson; “I don’t care if it’s horse piss, it works,” JFK said of the injections.

One of the most brazen—and successful—health-related coverups in presidential history has to be Grover Cleveland’s cancer surgery in 1893, a story Cleveland and his loyalists managed to keep under wraps for over two decades. That summer, during the first year of Cleveland’s second (nonconsecutive) term—and after a lifetime of cigar-smoking and tobacco chewing—the president needed an operation to remove a malignant tumor from the roof of his mouth. Using the cover story of a Long Island fishing trip, Cleveland had the surgery performed on a friend’s yacht. Under a single, swaying light bulb, a team of six doctors removed “five teeth, about a third of the upper palate, and a large piece of the upper left jawbone.”

The press was told “nothing but dentistry” had been performed during the president’s four-day voyage. One reporter for a Philadelphia paper got the scoop, but the administration damped down the rumors with a campaign to label the story “fake news.” And with a specially fitted rubber insert plugging the hole in his upper palate, Cleveland managed to look normal enough to pass (the fashion for bushy mustaches probably helped).

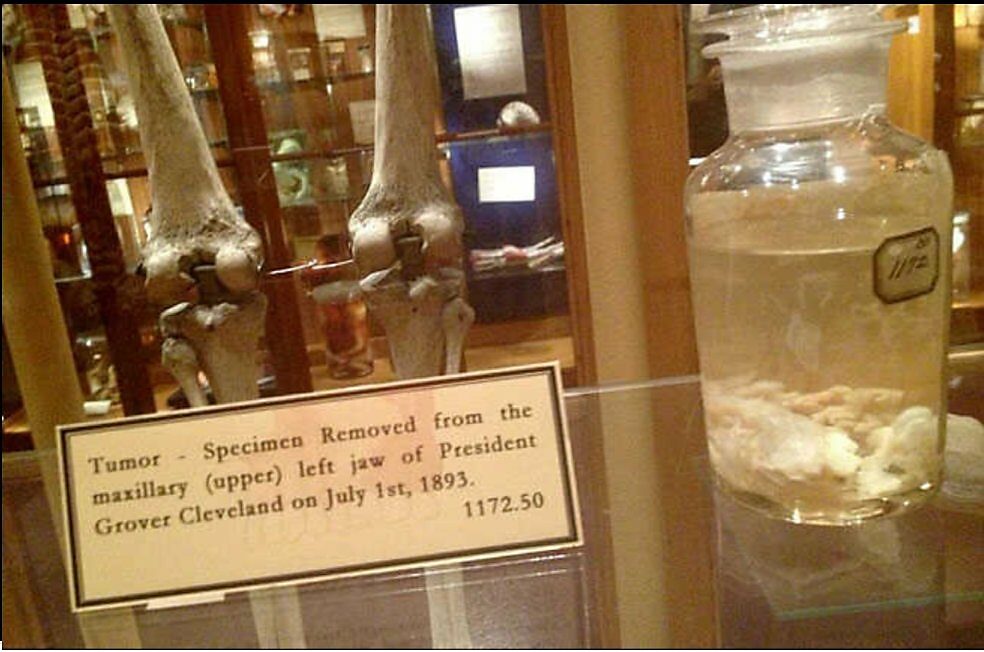

Today, at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, you can take a look at “the jaw tumor of President Grover Cleveland” (and chunks of presidential assassin Charles Guiteau’s brain, if you’re so inclined). The public didn’t learn the full truth about Cleveland’s surgery until 1917, nearly a decade after his death, when one of the doctors published an account in the Saturday Evening Post.

If today we have less reason to worry about such large-scale deception, that’s not due to any moral improvement in the political leadership class. Rather, such schemes have become much harder to pull off: it’s now impossible for a president to keep a two-hour hospital visit secret, let alone a multi-day “fishing trip” for major surgery. And, were the president’s health to take a dramatic turn for the worse, Melania Trump won’t be stepping in as a latter-day Edith Wilson.

To a far greater degree than in Cleveland’s, Wilson’s, or even Kennedy’s day, presidents are now under constant scrutiny from adversarial journalists, nonprofit watchdogs, and potential whistleblowers. In his 2012 book Power and Constraint, Jack Goldsmith coined the term “Presidential Synopticon” to describe “the gargantuan array of eyeballs gazing at the presidency, in secret and in public.” In Bentham’s Panopticon, the one watches the many; but in the Presidential Synopticon, the many watch the one. Modern technology has radically enhanced both forms of monitoring: presidents are now constantly on camera and at risk of being recorded even in situations of apparent privacy. Crowdsourced surveillance via social media makes even small-scale deception harder to pass off, even if excitable internet sleuths often get things wrong. These social and technological changes aren’t an unmitigated blessing, but they do make official secrets much harder to keep.