The death of Liu Xiaobo from liver cancer on July 13, under guard at a hospital in Shenyang, marks the passing of a great defender of freedom—a man who was willing to speak truth to power. As the lead signatory to Charter 08, which called for the rule of law and constitutional government, Liu was sentenced to 11 years in prison for “inciting the subversion of state power.” Before his sentencing in 2009, Liu stood before the court and declared, “To block freedom of speech is to trample on human rights, to strangle humanity, and to suppress the truth.” With proper treatment and freedom, Liu would have lived on to voice his support for a free society.

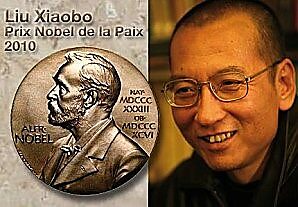

While Liu’s advocacy of limited government, democracy, and a free market for ideas won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, China’s leadership viewed him as a criminal and refused to allow him to travel to Oslo to receive the award. Instead, the prize was placed on an empty chair at the ceremony, a lasting symbol of Liu’s courage in the face of state suppression. Beijing also prevented liberal Mao Yushi, cofounder of the Unirule Institute, from attending the ceremony to honor Liu.

IdealMentre

The mistreatment of Liu, and other human rights’ proponents, is a stark reminder that while the Middle Kingdom has made significant progress in liberalizing its economy, it has yet to liberate the minds of the Chinese people or its own political institutions.

The tension between freedom and state power threatens China’s future. As former premier Wen Jiabao warned in a speech in August 2010, “Without the safeguard of political reform, the fruits of economic reform would be lost.” Later, in an interview with CNN in October, he held that “freedom of speech is indispensable for any country.”

Article 33, Section 3, of the PRC’s Constitution holds that “the State respects and protects human rights.” Such language, added by the National People’s Congress in 2004, encouraged liberals to test the waters, only to find that the reality did not match the rhetoric.

The Chinese Communist Party pays lip service to a free market in ideas, noting: “There can never be an end to the need for the emancipation of individual thought” (China Daily, November 16, 2013). However, Party doctrine strictly regulates that market. Consequently, under “market socialism with Chinese characteristics,” there is bound to be an ever-present tension between the individual and the state.

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal (September 22, 2015), President Xi argued that “freedom is the purpose of order, and order the guarantee of freedom.” The real meaning of that statement is that China’s ruling elite will not tolerate dissent: individuals will be free to communicate ideas, but only those consistent with the state’s current interpretation of “socialist principles.”

This socialist vision contrasts sharply with that of market liberalism, which holds that freedom is not the purpose of order; it is the essential means to an emergent or spontaneous order. In the terms of traditional Chinese Taoism, freedom is the source of order. Simply put, voluntary exchange based on the principle of freedom or nonintervention, which Lao Tzu called “wu wei,” expands the range of choices open to individuals.

Denying China’s 1.4 billion people a free market in ideas has led to one of the lowest rankings in the World Press Freedom Index, compiled by Reporters without Borders. In the 2016 report, China ranked 176 out of 180 countries, only a few notches above North Korea—and the situation appears to be getting worse. Under President Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power in preparation for this year’s Party Congress, the websites of liberal think tanks, such as the Unirule Institute, have been shut down, and virtual private networks (VPNs) are being closed, preventing internet users from circumventing the Great Firewall.

Liu’s death is a tragic reminder that China is still an authoritarian regime whose leaders seek to hold onto power at the cost of the lives of those like Liu who seek only peace and harmony through limiting the power of government and safeguarding individual rights.