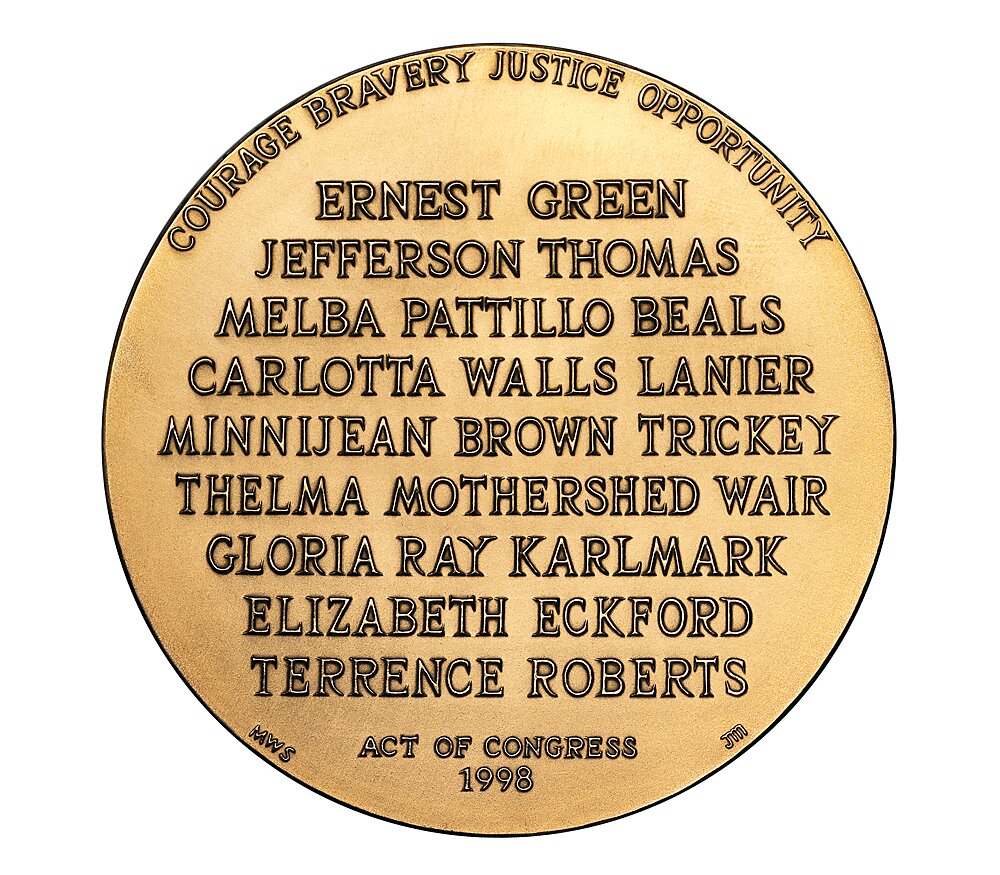

Today is the 60th anniversary of the desegregation of public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, a deeply disturbing event for the explosive racism it revealed, but also an inspiring episode for the courage displayed by the children who braved it.

One thing for which it serves as a reminder is that it was public schooling and government generally that for decades forced segregation. Recent attacks against school choice have glossed over this fact, as well as that the absence of choice meant even those who wanted something different were almost certainly hard-pressed to get it.

The anniversary also reminds us that repairing race relations that have been poisoned by centuries of slavery, Jim Crow, and still-present hate, racism, and racial suspicion, is not likely something that will happen quickly—would it were otherwise—including with any kind of public policy panacea. Too much history, too many emotions, and increasingly, diversity that makes race relations more than black and white, are all in play. Which may be another argument for school choice: we need to let myriad educational arrangements be offered because no solution might be right for any two people, much less the entire country. Different individuals—and that is what we are, though race is an often crucial component of our identities—may desire different discipline policies, or curricula, and by allowing numerous arrangements to proliferate we can discover which ideas work best, for whom, without education being a zero-sum, winner-take-all contest.

Alas, the Little Rock 60th anniversary has been eclipsed by President Donald Trump’s remark that National Football League owners should fire players who refuse to stand for the national anthem, resulting, in a few cases, in entire teams this weekend refusing to come out of locker rooms for the singing of the Star Spangled Banner. Perhaps this too offers a lesson in the dangers to race relations posed by government, in this case highlighting how politics can amplify divisions and animosity. What had been an ongoing but relatively calm national debate about some players taking a knee during the anthem to protest what they see as racial injustice in the country exploded into a massive, headline-dominating demonstration by players and owners. This is partly because the current president seems to revel in aggravating people. But anytime a politician comments on something it almost inherently becomes a more political—and politicized—issue, and politics by its nature tends to make people act in ugly and divisive ways.

This, too, suggests that the nation would be better off if we looked not for sweeping government solutions to racial divides, but to the maximum extent possible left it to individual people and communities—to civil society—to do the complex, highly personal work of healing and uniting.