William Galston’s

Wall Street Journal column, “Why Trade Critics Are Getting Traction,” asks why U.S. employment in manufacturing fell from 17.2 million in December 2000 to 12.3 million last year. He suggests that “import penetration from China [not Mexico] has been responsible for up to 20% of U.S. job losses.” But “up to” 20% explains very little, and that figure is at the high end of a range of estimates about 1999–2011 from a working paper by David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson. They speculate that “had import competition not grown after 1999” then there would have been 10% more U.S. manufacturing jobs in 2011. In that hypothetical sense, “direct import competition [would] amount to 10 percent of the realized job loss” from 1999 to 2011. Since 2007, however, the study’s authors find “a marked slowdown in import expansion following the onset of the global financial crisis, which halted trade growth worldwide.”

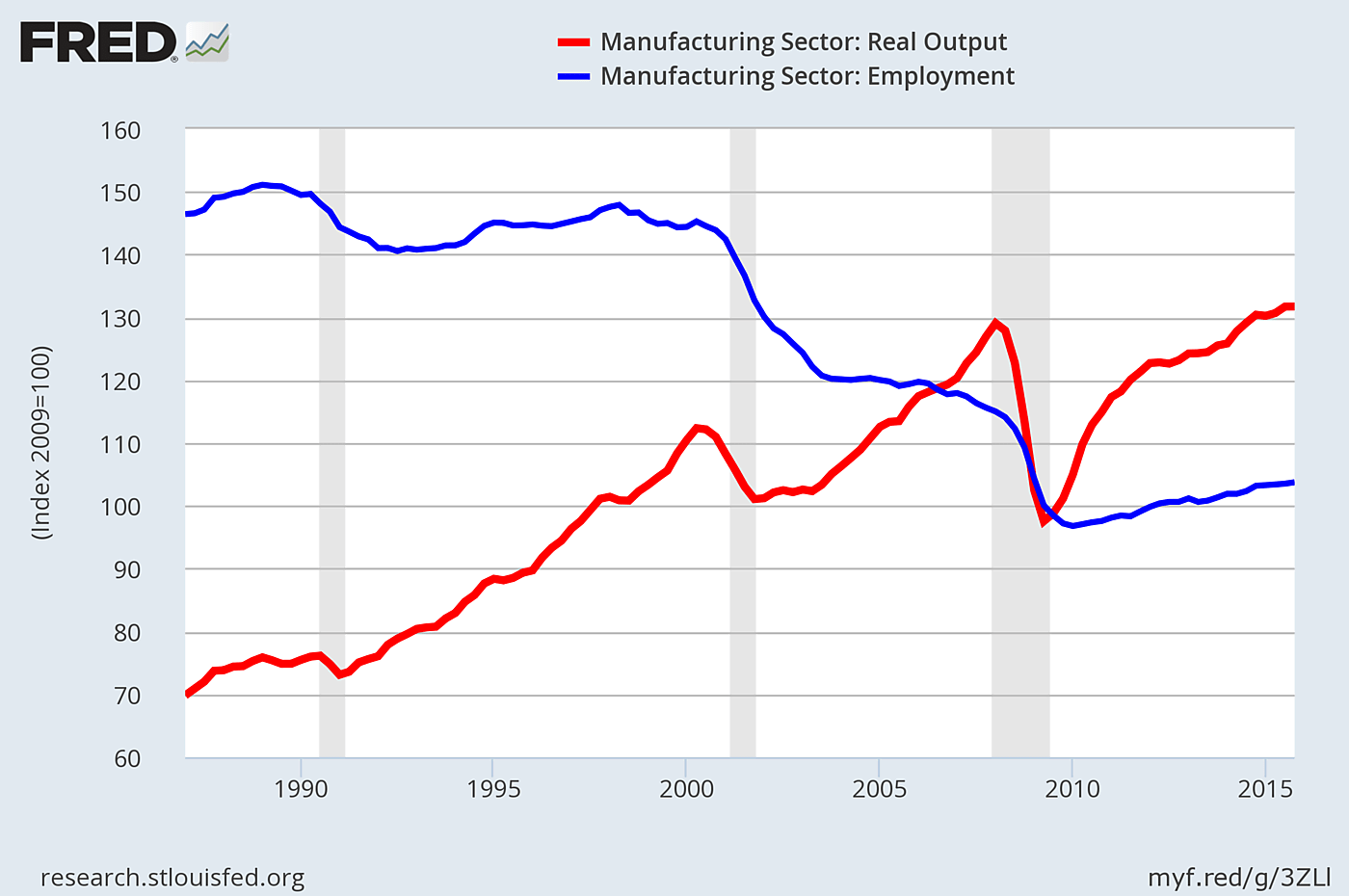

Deep recession and weak recovery is what slashed manufacturing jobs since 2007, not imports. In reality, imports always fall in recessions. Although Autor, Dorn and Hanson emphasize imports of consumer goods (clothing and furniture), nearly half of U.S. goods imports (47.7% last year) are industrial supplies and capital goods which are essential inputs into expanding U.S. production. That is a big reason why imports rise when U.S. industry expands and fall in slumps.

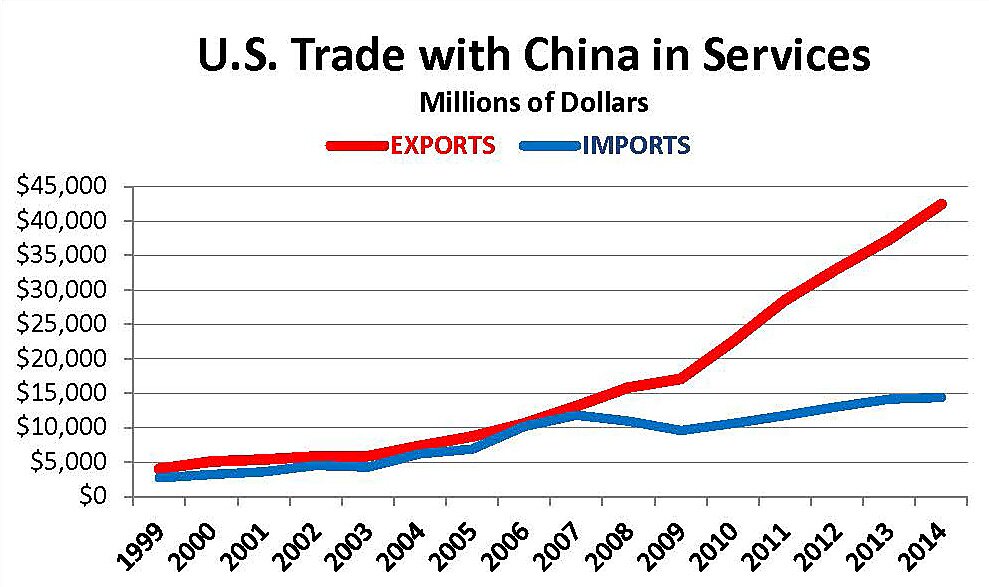

Even if “up to” 20% of manufacturing jobs lost since 2007 could be blamed on imports from China, as Galston claims, that need not mean the overall numbers of U.S. jobs were reduced. “There is no evidence,” writes Galston, “that increased competition from China has produced offsetting employment increases in other industries whose products are traded internationally [emphasis added].” Confining overall employment effects to “traded goods,” as Autor, Dorn and Hanson do, arbitrarily excludes services – such as financial and legal services, accounting, advertising, travel, telecom and insurance. Services account for 32% of U.S. exports, and the U.S. runs a large and growing trade surplus with China ($28 billion in 2014) and with the world ($233 billion). Dollars foreign firms earn by exporting goods to the U.S. are commonly used to import services from the U.S. or to invest in U.S. real and financial assets; both those activities create U.S. jobs. Hollywood, Madison Avenue and Wall Street are big, high-wage U.S. exporters.

Confining the job impact to traded goods also excludes U.S. jobs in transporting, wholesaling and retailing Chinese goods (Walmart, Amazon…), as well as shipping U.S. exports to China and Hong Kong. Incidentally, the U.S. ran a $30.5 billion trade surplus with Hong Kong last year, which isn’t counted trade with China though it really is.

Galston acknowledges that “rising productivity” [output per worker] is “part of the story” about manufacturing jobs. In fact, it is essentially the whole story from 1987 to 2007, when U.S. manufacturing output nearly doubled. The deep recession and slow recovery explain what happened to manufacturing jobs over the past ten years, not foreign trade.