Adam Davidson of the New Yorker has written a profile of Donald Trump’s trade adviser Peter Navarro. Here’s a key excerpt: “Navarro’s views on trade and China are so radical, however, that, even with his assistance, I was unable to find another economist who fully agrees with them.”

That’s the big picture of the trade views of Trump/Navarro. Now here’s a closer look at a very specific claim in a Trump campaign memo co-authored by Navarro. This kind of claim is, in my view, very enlightening about how this crowd approaches trade policy:

Over the last 25 years, Bill and Hillary Clinton have championed one-way deals like 1993’s NAFTA, China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization, and the 2012 South Korea-US Free Trade Agreement. These poorly negotiated deals benefit the elite corporate interests that finance the Washington politicians even as they impoverish our heartland and destroy the livelihoods and lives of working Americans.

…

Michigan farmers lost out too. U.S. exports to Canada and Mexico of cattle – one of Michigan’s top agricultural products — fell 59 percent in the first 22 years of NAFTA.

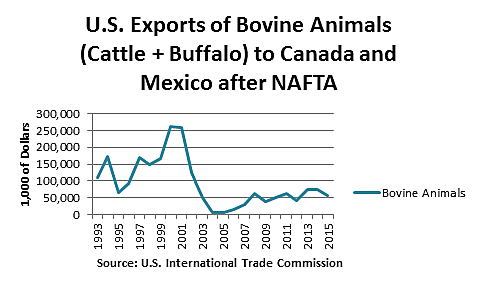

What’s nice about this claim about cattle exports is that, unlike many of the vague criticisms people make about trade agreements, this one can be tested: Did these exports actually fall? The authors don’t give a citation for the data, which makes it difficult to double-check, but here’s some data from the U.S. International Trade Commission on exports of “bovine animals” (including cattle and buffalo, but mostly made up of cattle):

It turns out he’s roughly correct in terms of the 22 year trend. So does that mean he has a point about NAFTA? Could lowering Mexican and Canadian tariffs through the NAFTA somehow have hurt U.S. exports, contrary to all logic? The answer is no, for two reasons.

First, take a look at the export trend over time. Notice how the numbers increase for the first ten years or so, then suddenly drop down close to zero. That drop was due to BSE disease being found here in the U.S. So it wasn’t NAFTA that got in the way of U.S. exports, but a disease outbreak. Exports of cattle have improved since then, although they have not reached pre-BSE levels.

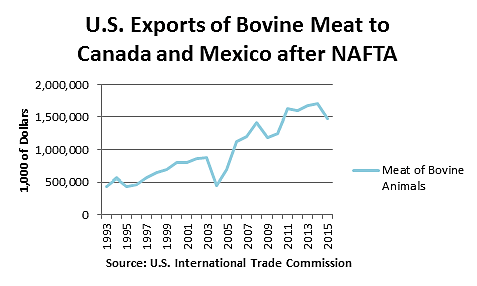

Second, there’s also another little trick in their data. When you see the word cattle, you might think of beef, and assume U.S. beef exports fell. But cattle actually means cattle. When’s the last time you bought cattle? I haven’t bought any cattle recently, but I have bought a fair amount of beef. So let’s look at U.S. beef (again, including a small amount of buffalo) exports to Canada and Mexico over the time period he uses:

What you see now is a large increase in U.S. beef exports (almost tripling since the time of NAFTA), with a brief fall during the U.S. BSE scare.

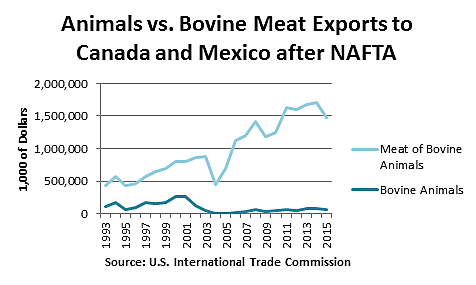

And when you put the figures together in one table, you can see how the beef figures dwarf the cattle figures, and thus how this sector of the U.S. agriculture industry saw trade expand after NAFTA:

Thus, the story here is really about how U.S. beef exports rose after NAFTA. What we have with the Navarro claim is someone cherry-picking data in an effort to support a broader point. But if you go beyond the selective statistics, you get the story you would expect: Lowering Mexican and Canadian tariffs correlates with a big rise in U.S. exports.