The headline on the latest Washington Post-ABC News poll was “Poll Finds Americans Pessimistic, Want Change.” And why would they not, with a floundering war, civil liberties abuses, soaring federal spending, and the prospect of four years under the rule of Hillary or Rudy? But there are some signs in the accompanying data that seem to confirm the existence of libertarian voters, voters who don’t fit into either the liberal or conservative box.

One of the questions was an old standby: “Generally speaking, would you say you favor smaller government with fewer services, or larger government with more services?” Smaller government won by 50 to 44 percent, but the Post noted that that was a much smaller margin than previous surveys had shown, indicating the damage the Bush administration and the congressional Republicans have done to the “smaller government” brand. Still, a six-point margin is better than Bush achieved in his two elections, and 50 percent is better than Bill Clinton ever did.

The next question in the survey was “Do you think homosexual couples should or should not be allowed to form legally recognized civil unions, giving them the legal rights of married couples in areas such as health insurance, inheritance and pension coverage?” Respondents said they should, by 55 to 42 percent, up from earlier surveys.

So if you take support for smaller government as an indicator of libertarian-conservative sentiment, and support for civil unions as an indicator of libertarian-liberal sentiment, then the libertarian position got a small majority on both questions.

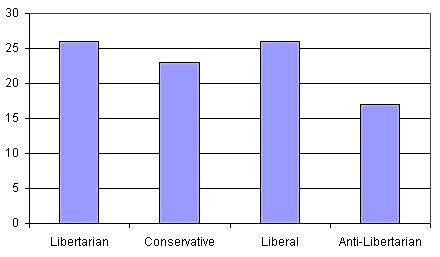

I asked Post polling director Jon Cohen if it was possible to get crosstabs for those questions, and he generously supplied them. So we can use those two questions to construct a four-way ideological matrix. I categorize the responses this way: Roughly speaking, libertarians support smaller government and civil unions. Conservatives support smaller government and oppose civil unions. Liberals support larger government and civil unions. And the fourth group–variously called statists, populists, or maybe just anti-libertarians–support larger government and oppose civil unions. And thus we find that on these two questions 26 percent of the respondents are libertarians, 26 percent liberals, 23 percent conservatives, and 17 percent anti-libertarians:

A few other reflections on these questions: It’s often been noted that how you ask the question can shape the answers. For instance, if you offer three positions, people will tend toward the middle option. Polls usually show that a majority of voters oppose gay marriage, while a slimmer majority now support legal recognition for domestic partnerships or civil unions. But if you give respondents three options–marriage, civil unions, or no legal recognition–the opposition is reduced, and polls tend to show a strong majority supporting some form of recognition. In the 2004 exit poll, for instance, the results were 25 percent for marriage, 35 percent for civil unions, and 37 percent opposed to both.

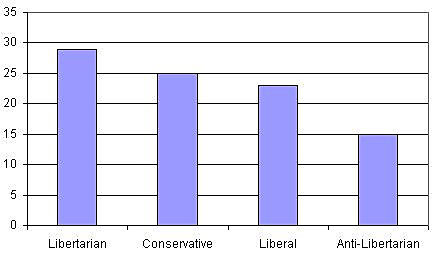

I’ve always thought the “smaller government” question is incomplete. It offers respondents a benefit of larger government–“more services”–but it doesn’t mention that the cost of “larger government with more services” is higher taxes. The question ought to give both the cost and the benefit for each option. A few years ago a Rasmussen poll did ask the question that way. The results were that 64 percent of voters said that they prefer smaller government with fewer services and lower taxes, while only 22 percent would rather see a more active government with more services and higher taxes. A similar poll around the same time, without the information on taxes, found a margin of 59 to 26 percent. So it’s reasonable to conclude that if you remind respondents that “more services” means higher taxes, the margin by which people prefer smaller government rises by about 9 points. That suggests that adding “higher taxes” to the Post question would have widened the margin from 6 to 15 points, or perhaps a response of 55 percent for smaller government and 40 percent for larger government. (Note that Jon Cohen and the Post are not responsible for any of this speculation.)

And when you adjust the four-way division on the basis of our Platonic ideal of the two questions, then we get slightly more libertarians and conservatives and fewer liberals and anti-libertarians—29 percent libertarians, 25 percent conservatives, 23 percent liberals, and 15 percent anti-libertarians:

Yet more evidence that there is a libertarian vote that is indeed different from liberals and conservatives.