Last week, Ross Tilchin at Brookings asked whether a stronger appeal to libertarian voters could help Republicans win elections. He was skeptical:

First, according to the [Public Religion Research Institute] PRRI poll, libertarians represent only 12% of the Republican Party. This number is consistent with the findings of other studies by the Pew Research Center and the American National Election Study. This libertarian constituency is dwarfed by other key Republican groups, including white evangelicals (37%) and those who identify with the Tea Party (20%).

Tilchin’s use of the phrase “consistent with” to describe the findings of other studies is, well, interesting. In fact, other studies have found almost three times more libertarians in the Republican Party than PRRI’s poll.

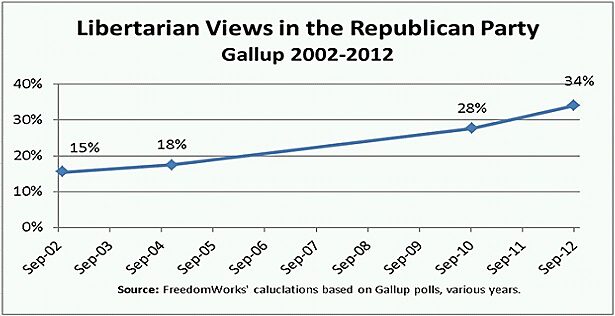

As I blogged at Cato and found in a study for FreedomWorks, libertarian views in the Republican Party are the highest level in a decade. According to my analysis of American National Election Studies data, libertarians represent 35 percent of the Republican Party, an increase of 9 percentage points since 2000. Gallup’s own studies confirm this trend: libertarian views represent 34 percent of the Republican Party, a 19 percentage point increase since 2002. See chart below.

How exactly are 35 percent and 34 percent “consistent with” 12 percent? A better word to describe PRRI’s finding would be “outlier.”

As Karlyn Bowman pointed out at Brookings’ own forum on the subject, PRRI’s finding that libertarians are 7 percent of Americans is at the very low end of other estimates of libertarian voters. In 2011, Pew’s Typology Survey found 9 percent libertarians. In 2012, Gallup’s Governance Survey found 25 percent libertarians. Emily Ekins averaged seven Reason-Rupe polls from 2011 to 2012 and found libertarians represented 24 percent of Americans.

David Boaz and I, in our original study on the “Libertarian Vote,” took a conservative middle ground, estimating that libertarians were 15 percent of voters in 2004. Of course, even a conservative 15 percent is twice as many libertarians as the 7 percent PRRI choose to recognize. And, picking a smaller number, as PRRI does, makes it easier to question or dismiss libertarians’ importance.

Fortunately, there’s a simple way to make PRRI’s data “consistent with” other findings. PRRI’s methodology defines libertarians based on nine issue questions, ranking answers for their libertarian-ness on a 7‑point scale, with 1 being the most libertarian, and 7 being the least. Robbie Jones and the other authors at PRRI defined “libertarians” as respondents who score between 9 and 25 points. Respondents who scored 26–33 were categorized as “lean libertarian.”

If we add PRRI’s two categories of “libertarian” and “lean libertarian,” the data show 23 percent of Americans are broadly libertarian. Using this definition, PRRI’s data are actually quite “consistent with” the findings from other studies:

- PRRI’s data show libertarians represent 36 percent of Republican Party in 2013, consistent with ANES and Gallup data;

- Libertarians are about the same size as other key constituencies in the Republican Party, such as white evangelicals;

- Libertarians represent 56 percent, or half, of the tea party, consistent with the finding in Emily Ekins and my Cato study, “Libertarian Roots of the Tea Party.”

Of course, how to define libertarians and who counts as a “real” libertarian is a favorite parlor game of libertarian intellectuals. Do you count only those “hard core” libertarians who have rigorously consistent beliefs? Or, do you count those who hold broadly libertarian views or instincts that are different than conservatives or liberals? If you think this is a simple question, just amuse yourself with GMU economist Bryan Caplan’s 64-question “Libertarian Purity Test.”

What is missing from the PRRI study is that it doesn’t deal with this past literature, or make an argument for its methodology, one way or the other. Particularly when your definition of libertarians is an outlier, your readers deserve to have the finding placed in context.

Regardless, the very fact that PRRI and Brookings did this study is an important milestone. For many years, libertarian voters were a research topic of interest to a small group of think tankers, writers, and contrarian political strategists, as well as a handful of curious academics. But when the Ford Foundation funds a major study on libertarian voters, and Brookings hosts a panel with scholars from PRRI, AEI, Cato, and the Ethics & Public Policy Center, I take this as a sign that libertarians are no longer politically ignorable.

That’s a good thing.