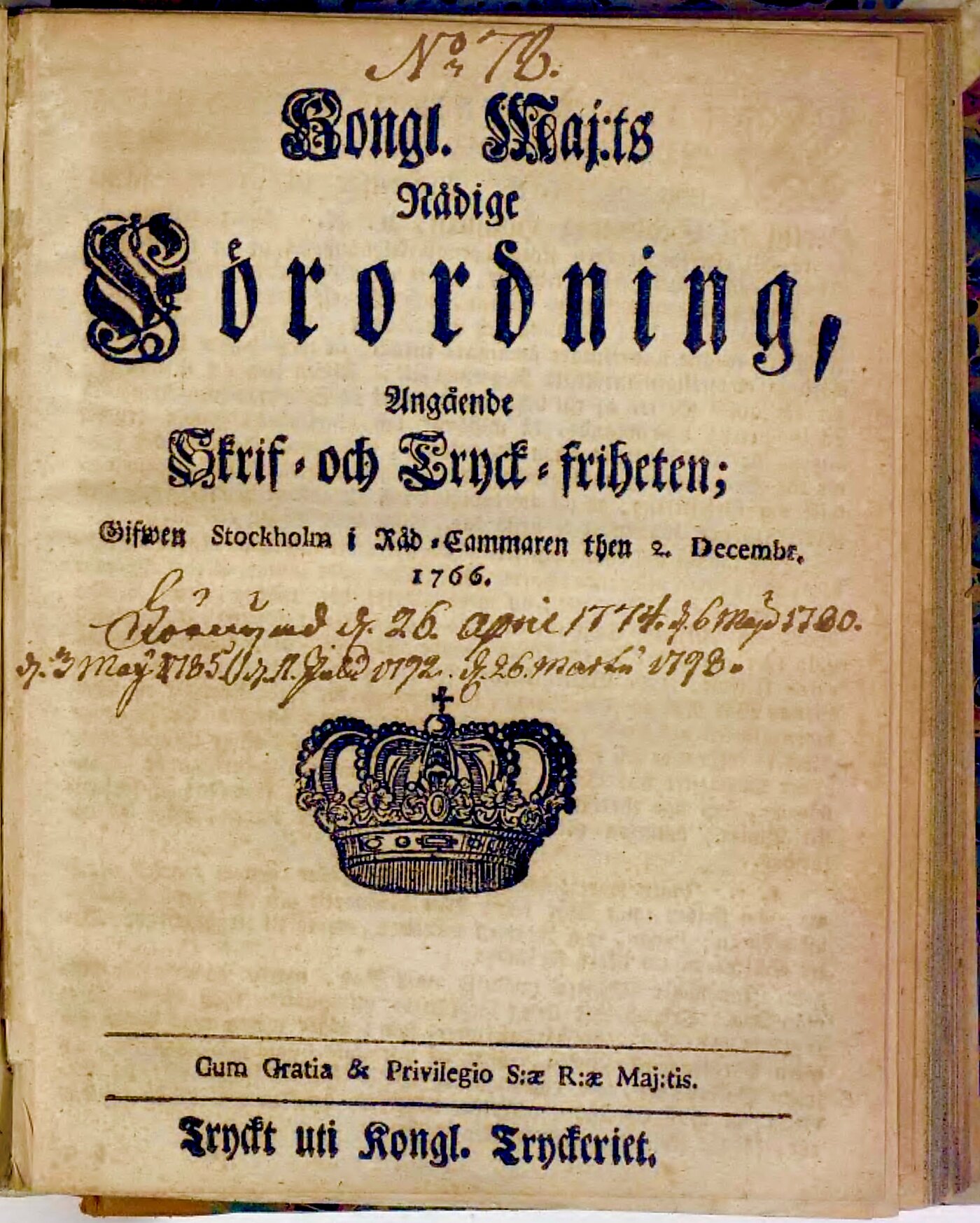

UNESCO has just designated the Swedish Freedom of the Press Act of 1766 a “Memory of the World.” It’s a well-deserved honor. This more than 250-year old document, enacted during a period of strong parliamentary power in Sweden, is the world’s first freedom of the press act, signed into law ten years before the United States of America even existed.

In defense of “unrestricted mutual enlightenment,” the 1766 act created a constitutional right to publish one’s thoughts and ideas, abolished censorship (in everything but theological texts) and introduced the principle of public access to official records. The English parliament had let its censorship lapse as early as 1695, but it gave no legal protection to the press, so it could still be subjected to arbitrary intervention.

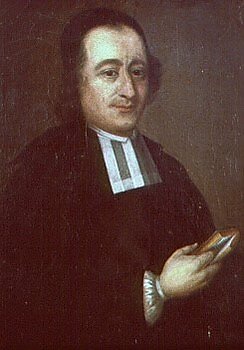

This is in itself enough to make Sweden’s 1766 act a milestone in libertarian history, but it gets better. The law’s author was the Ostrobothnian priest Anders Chydenius, one of Sweden’s earliest and most principled classical liberals. Chydenius was a radical natural rights-thinker and a staunch defender of limited government, free markets, low taxes and open migration: “I speak only for the one small, but blessed word, freedom. I believe that nature, in this, as in so many other things, left to itself, accomplishes far more than many elaborate and ingenious plans.”

Among his many short books, in 1765 — 11 years before Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations — Chydenius published the powerful pamphlet The National Gain, explaining how the price mechanism and the profit motive make markets self-regulating and engines of wealth creation. The great 20th century economic historian Eli Heckscher described it as “an almost classically clear and simple exposition of the basic views of economic liberalism and a contribution which might well have gained international fame, had it appeared at the time in any of the major languages.”

Chydenius’ campaign for free trade for Ostrobothnia’s farmers made him popular and he was elected to the Swedish parliament 1765/66, where he wrote the freedom of the press act. Despite fierce opposition from the nobles, Chydenius’ skills, incredible work-ethic and seductive rhetoric carried the day.

As present-day authoritarians imprison dissenters, campus leftists cancel their way to utopia and national conservatives try to silence “woke corporations,” Chydenius’ ideas and accomplishments remain a source of inspiration: “the liberty of a nation is always proportional to the freedom of its press, so that neither can exist without the other. Where the press is closed under some kind of authority, it is an unfailing sign of the nation’s shackles.”

Of course much speech is uninformed or false, accepted Chydenius, and therefore, he insisted, we need more and better speech.