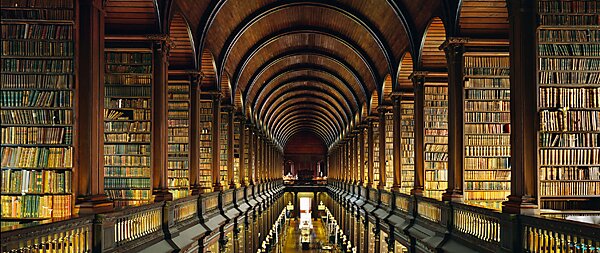

If you wanted a liberal arts education in 1499, you were probably out of luck. But, if you happened to be a 0.01 percenter, you might have been able to saddle up the horse and ride to Oxford or Cambridge. Because that’s where the books were. Books didn’t generally come to you, you had to go to them.

Today, every one of us has more works of art, philosophy, literature, and history at our fingertips than existed, worldwide, half-a-millennium ago. We can call them up, free or for a nominal charge, on electronic gadgets that cost little to own and operate. Despite that fact, we’re still captives to the idea that a liberal arts education must be dispensed by colleges and must be acquired between the ages of 19 and 22.

But the liberal arts can be studied without granite buildings, frat houses, or sports venues. Discussions about great works of literature can be held just as easily in coffee shops as in stadium-riser classrooms—perhaps more easily. Nor is there any reason to believe that there is some great advantage to concentrating the study of those works in the few years immediately after high school—or that our study of them must engage us full-time. The traditional association of liberal arts education and four-year colleges was already becoming an anachronism before the rise of the World Wide Web. It is now a crumbling fossil.

Handing colleges tens of thousands of dollars—worse yet, hundreds of thousands—for an education that can be obtained independently at little cost, would be tragically wasteful even if the college education were effective. In many cases, it is not. Research by Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa reveals that almost half of all college students make no significant gains in critical thinking, complex reasoning, or written communication after two full years of study. Those are skills that any liberal arts education should cultivate. Even among the subset of students who linger for four years at college, fully one-third make no significant gains in those areas.

And yet, instead of recognizing the incredible democratization of access to the liberal arts that modern technology has permitted, and the consequent moribundity of this role of colleges, public policy remains mired in a medieval conception of higher education. Politicians compete to promise what they think young people want to hear: more and larger subsidies for college fees. Even if perpetuating a 15th century approach to higher education were in students’ interests—which it clearly is not—increased government subsidies for college tuition would not achieve that goal. We have tripled student aid in real, inflation-adjusted dollars since 1980, to roughly $14,000 per student, and yet student debt recently hit an all-time high of roughly $1 trillion. And barely half of students at four-year public colleges even complete their studies in six years. Aid to colleges is good for colleges, but it is an outlandish waste of resources if the goal is to improve the educational options available to young people.

These same realities apply, to an only slightly lesser extent, to the sciences and engineering. In those areas, colleges sometimes have equipment and facilities of instructional value that students could not independently afford. But even in the sciences and engineering, such cases are limited. It is perfectly feasible for an avid computer geek to learn everything he or she needs to know to work in software engineering by doing individual and group projects with inexpensive consumer hardware and software. This was even possible before the rise of the Web. My first direct supervisor at Microsoft was a brilliant software architect hired right out of high school… in the 1980s.

Though most politicians have been slow on the uptake, the public seems increasingly aware of all this. A Pew Research survey finds that 57 percent Americans no longer think college is worth the money. So why are they still sending their kids there? Habit is no doubt part of the picture, but so is signaling. People realize that colleges are instructionally inefficient, but being accepted to and graduating from an academically selective one signals ability and assiduity to potential employers.

So what’s the solution? Alternative signaling options and better hiring practices would be a good start. Anyone who studies hard for the SAT, ACT, GRE, or the like, and scores well, can send the academic ability signal. But in the end, employers want more than academic ability. What they really want are subject area expertise, a good work ethic, an ability to work smoothly with a variety of people, and, for management, leadership ability. Any institution that develops good metrics for these attributes, and issues certifications accordingly, will provide an incredibly valuable service for employers. Students would then be free to study independently, occasionally paying for instruction where necessary, and then seek a certification signaling what they’ve learned. In the meantime, job candidates can create a portfolio of work on the Web showing what they know and can do (a “savoir faire”)—which would be more useful to employers than most resumes.

What is certainly not useful is raising taxes still further in a time of economic difficulty in order to pad the budgets of colleges and encourage students to take on yet more college debt.