Donald Trump recently unveiled a new child care plan whereby the government will force employers to give time off to new mothers in exchange for some shuffling of the tax code. Mothers do tend to benefit from such schemes but they also end up paying for their time off in other, indirect ways like lower wages. Forcing employers to pay their female employees to take time off decreases the labor demand for child-bearing age women and increases their supply, thus lowering their wages. Economist Larry Summers, former Director of the National Economic Council during President Obama’s first administration, wrote a fantastic paper explaining this effect.

Many firms have maternity leave policies that balance an implicit decrease in wages or compensation for working-age mothers with time off to care for a newborn. The important point about these firm-specific policies is that they are flexible. Some women want a lot of time off and aren’t as sensitive to the impact of their careers while others want to return to work immediately. A one-size fits all government policy will remove this flexibility.

Regardless of the merits or demerits of Trump’s plan, economists Patricia Cortes and Jose Tessada discovered an easier and cheaper way to help women transition from being workers to being mothers who work: allow more low-skilled immigration. In a 2008 paper, they found:

Exploiting cross-city variation in immigrant concentration, we find that low-skilled immigration increases average hours of market work and the probability of working long hours of women at the top quartile of the wage distribution. Consistently, we find that women in this group decrease the time they spend in household work and increase expenditures on housekeeping services.

The effect wasn’t huge but skilled women did spend less time on housework and more time working at their job.

Younger women with higher educations and young children would be the biggest beneficiaries from an expansion of childcare services provided by low-skilled immigrants. There are about 5.4 million working-age women with a college degree or higher that also have at least one child who is under the age of 8 (Table 1). Almost 78 percent of them are employed, 2 percent are unemployed looking for work, and 21 percent are not in the labor force.

Table 1

Age of Youngest Child by Mother’s Employment Status, College and Above Educated, Native-Born Mothers, Ages 18–64

|

Less than 1 Year Old |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

Total |

|

| Working |

706,534 |

700,014 |

537,301 |

463,119 |

405,006 |

476,014 |

420,776 |

476,092 |

4,184,856 |

| Unemployed |

8,201 |

12,810 |

22,617 |

14,560 |

9,126 |

10,664 |

11,548 |

15,450 |

104,977 |

| Not in Labor Force |

207,338 |

221,078 |

170,360 |

142,461 |

124,305 |

103,283 |

79,827 |

79,621 |

1,128,271 |

| Total |

922,072 |

933,902 |

730,278 |

620,140 |

538,437 |

589,960 |

512,151 |

571,163 |

5,418,104 |

Source: March CPS, 2014.

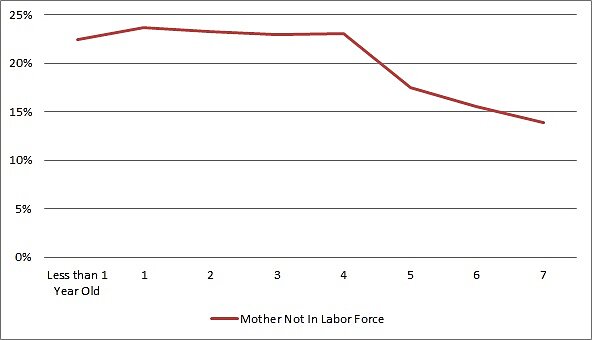

As the youngest child ages, the percentage of women not in the labor force also shrinks, probably because less labor at home is required to take care of them (Figure 1). Cheaper childcare provided by low-skilled immigrants can increase the rate at which these skilled female American workers return to the job after having a child.

Age of Youngest Child by Percent of Mothers Not in Labor Force, College and Above Educated, Native-Born Mothers, Ages 18–64

Source: March CPS, 2014.

Trump’s immigration policy doesn’t allow him to propose helping mothers in this cheaper way. Allowing more lower-skilled immigrants to help with childcare does conflict with Trump’s position on cutting LEGAL immigration. Liberalizing low-skilled immigration will give more options to working mothers, boost opportunity for immigrants, increase the take-home pay of working mothers (complementarities), allow more Americans with higher skills to enter the workforce, and slightly liberalize international labor markets. It’s a win-win for everybody except for the current government protected, highly regulated, heavily licensed, and very expensive day care industry.

It’s hard being a new mother. My wife’s ability to deliver, feed, and care for our three-month-old son with only a short break from her job is impressive. Instead of lowering my wife’s wages indirectly with an ill-conceived family leave policy, it would be better to expand her ability to hire immigrants to help out at home. More choices, not mandated leave, will lead to better outcomes. If only Trump’s immigration platform didn’t make this solution impossible.