Back in July, I shared here some thoughts concerning the Fed’s conference in Chicago that month, which was dedicated to a review of its tools, strategies, and communications. Among other things, I said I was disappointed by the short-shrift given to NGDP targeting by Lars Svensson in his paper evaluating alternatives to strict inflation-rate targeting.

That paper’s dismissive treatment of NGDP targeting met with some sharp replies from audience members sympathetic to the idea. In response to these, Professor Svensson has since revised it, moving its original, terse discussion of NGDP targeting from an appendix to the main body, and enlarging upon it.

These changes don’t alter the paper’s conclusion, to wit: that NGDP targeting is inferior to several other possible monetary policy strategies, and particularly to average inflation targeting. But they do make it easier to spot some subtle fallacies upon which that negative verdict rests. By pointing-out these fallacies, I hope I may help to convince both Professor Svensson himself and others to better appreciate NGDP targeting’s merits.

NGDP Targeting as a Recipe for Central Bank Inaction

Professor Svensson’s critique starts with his understanding that under NGDP targeting there is really “only one target variable, nominal GDP, and thus a single mandate, stabilizing NGDP.” This starting point is itself problematic in so far as it suggests that proponents of NGDP targeting view it as an end in itself, rather than as a means for achieving other objectives. But I will come to that later.

The single-mandate interpretation of NGDP targeting implies a very simple central bank “loss function,”

Since Yt, the instantaneous growth rate of nominal income, is equal to the sum of the rate of change of the price level, pt, and the rate of change of real output, yt, the function can be rewritten thus:

The expanded loss function implies, Professor Svensson says, that under NGDP targeting “the price level and the GDP level are perfect substitutes.” Any given NGDP target is, in other words, consistent with a continuum of inflation- and output-gap combinations, only one of which actually consists of zero gaps for both output and inflation.

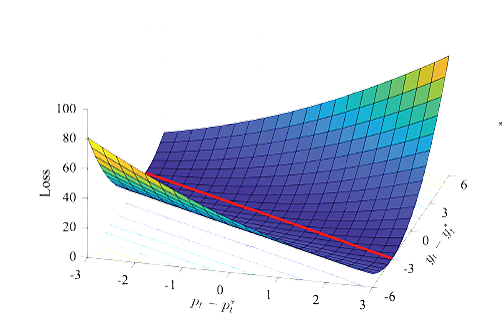

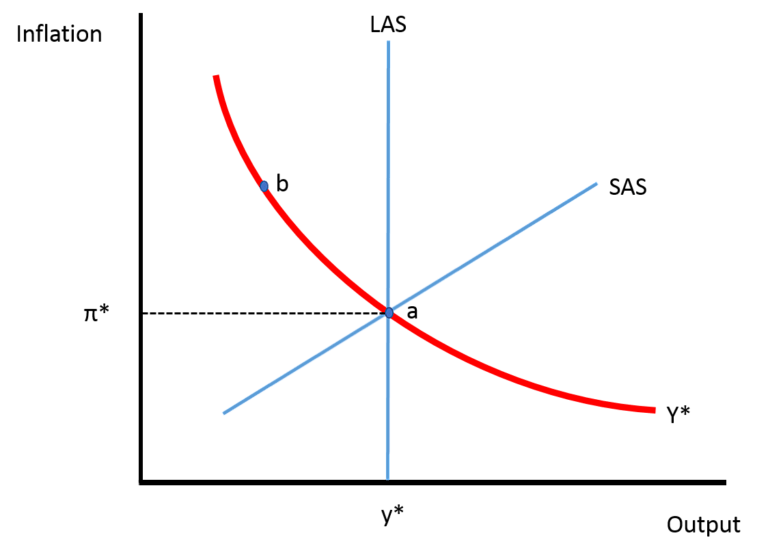

In the 3‑D image below, taken from the revised paper, the red line shows the continuum in question, with the point at which both inflation and output are at their respective target and potential levels at its midpoint. The other points on the red line involve non-zero, though symmetrical, inflation and output gaps.

Allowing the unemployment gap to be a simple function of the output gap, the conclusion supposedly follows that, despite hitting its target, an NGDP-targeting Fed could end up letting both inflation and unemployment differ considerably from their ideal levels. Put differently, the Fed’s “reaction function” might not call for it to react at all to situations in which both inflation and output wander far from levels consistent with the spirit, if not the letter, of the Fed’s dual mandate.

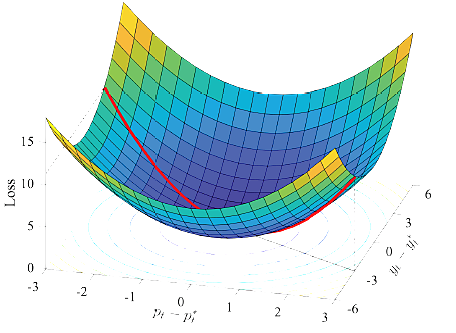

For comparison, here is the corresponding figure for flexible price-level targeting:

In this case, the central bank’s loss is minimized only when both inflation and output are at their preferred (zero gap) levels. It thus appears that a price-level target is more consistent with the Fed’s dual mandate and less likely to be costly to society, than an NGDP target.

At first glance, these arguments seem damning. They raise the spectre of NGDP-targeting FOMC members resting easy despite the fact that output has fallen far below its potential level, because inflation has risen just as sharply! But that, Professor Svensson claims (quoting John Williams’ colorful language), is a possible consequence of a policy which, instead of taking both measures of economic well-being seriously, “mashes” them together.

However, a closer look at Professor Svensson’s argument shows it to rest upon three fallacies. I’ll call them the Fallacy of the Phony Equilibria; the Fallacy of the Phantom Instrument; and the Fallacy of the Fictitious Loss.

The Fallacy of the Phony Equilibria

As we’ve seen, the chief concern raised by Professor Svensson’s paper is that, because any given NGDP level is consistent with a continuum of inflation and output gap combinations, an NGDP-targeting Fed could fail to take action to improve upon situations involving substantial but symmetrical inflation and output gaps.

But is that a real danger? Not really. Although it’s true that a given NGDP level is consistent with all sorts of inflation and output combinations, including some nasty ones, it is so only in a strictly arithmetical sense. It doesn’t follow that an NGDP-targeting Fed would actually risk exposing the U.S. economy to any one of the many possible combinations of output and employment consistent with whatever NGDP level it chooses to target.

Why not? The explanation starts with the prosaic observation that, although untold combinations of inflation and output may all add up to the same NGDP level, the actual levels of inflation and output an economy generates depend not merely on the level of NGDP its central bank targets, which determines the state of aggregate demand, but on the interaction of that level and the economy’s aggregate supply schedule, which determines how rapidly prices rise in response to the given NGDP growth rate. Given some state of aggregate supply, a particular NGDP target results in a unique inflation and output combination.

Here, to illustrate the point, is a simple AS-AD (for aggregate supply and demand) diagram. I’ve drawn it in inflation-output space (rather than the usual price level-output space) to allow for a positive long-run inflation target. I’ve also assumed for the moment that the Fed’s NGDP target happens to be consistent with the supposed ideal of zero output and inflation gaps, as represented by the equilibrium point a.

In this picture, as in Professor Svensson’s paper, y* stands for some level of potential output, which the Fed must treat as given, while π* corresponds to p*, the Fed’s inflation target. A policy of NGDP level targeting is represented by replacing the usual aggregate demand schedule with a constant NGDP schedule, where Y* represents the targeted NGDP growth rate. The fixed NGDP schedule, shown as a red line, is the exact counterpart of the red line in the first 3‑D image reproduced above. Although the other points on the NGDP schedule are consistent with Y – Y*= 0, they involve non-zero inflation and output gaps, and so are not ideal. (The areas to the northeast and southwest of Y* correspond to the purple, blue, green, and yellow portions of Professor Svensson’s 3‑D picture.)

Now, it would indeed be bad news if the U.S. could find itself on one of the “bad” points on its stable NGDP schedule, like point b in the diagram above, with nonzero but offsetting inflation and output gaps. But how could it? For it to end up at point b, the aggregate supply schedule would have to shift to the left. Such a shift would, however, imply a like change in potential output. So although it’s true that keeping NGDP fixed despite such a shock would result in a positive inflation gap, it wouldn’t lead to a corresponding, negative output gap.

Because they can’t be realized in practice, the non-zero symmetrical inflation and output gaps along the red line segment are actually quite irrelevant to assessing the merits of NGDP targeting. In worrying about them, Professor Svensson appears to fall victim to the Fallacy of the Phony Equilibria.

The Fallacy of the Phantom Instrument

Further reflection reveals another problem with Professor Svensson’s argument, to wit: that the 0, 0 inflation-output gap it treats as ideal may not always be achievable in practice, at least in the short run.

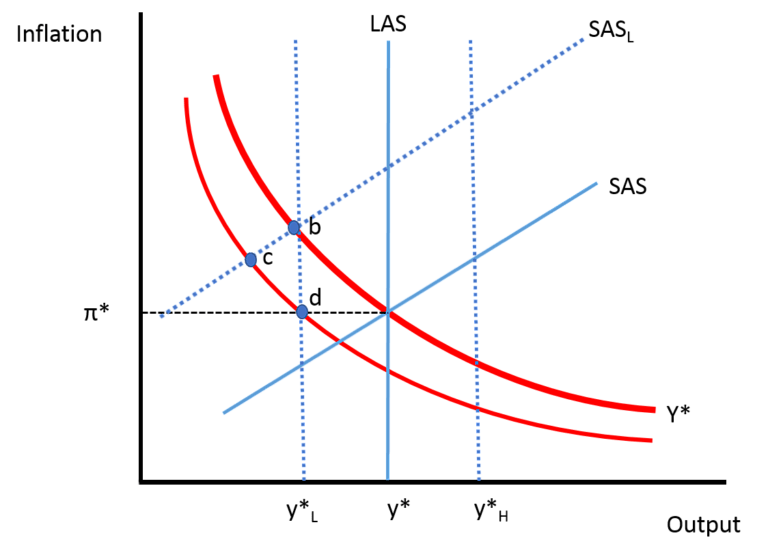

Thus, suppose that, instead of maintaining a constant NGDP level, upon being confronted with the aforementioned adverse supply shock, the Fed lowers its NGDP target to a level consistent with an unchanged long-run inflation rate. I show that case in the next figure which, instead of showing just one potential output (or long-run aggregate supply) level, allows potential output to vary between high and low levels surrounding its mean, with the low level coinciding with point b.

Suppose that, when confronted by such a low realized level of potential output, the Fed tries to keep inflation on target. Can it do so while also maintaining a zero output gap? Probably not. Because any aggregate demand innovation entails, ipso facto, some movement along an upward-sloping short-run AS schedule, by endeavoring to keep inflation unchanged the Fed is instead likely to create a temporary, negative output gap, coinciding with the temporary equilibrium shown as point c. (If, on the other hand, the Fed tried to keep above-average output growth from causing disinflation, it would risk boosting output above its sustainable level. It might, in other words, fuel a boom-bust cycle.)

More generally, in claiming that NGDP targeting involves a flawed Fed reaction function, Professor Svensson seems to assume that the Fed can generally improve upon it using a different policy. That is, he assumes either that there’s always some action it could take that would reduce both gaps to zero, or that it can at least reduce one of the gaps without increasing the other. But to do so is to commit the Fallacy of the Phantom Instrument.

Although the name is my invention, it was the estimable Nick Rowe who drew my attention to the fallacy in question when I showed him an early version of this essay. As Nick explained to me then,

Yes, if the Central Bank had TWO INDEPENDENT instruments, and so could control BOTH P (price level) and y (real GDP) at the same time, then an NGDP target would be a bad idea. …But it does NOT have two independent instruments that can move P and y in opposite directions. It can either loosen (raise both P and y), or tighten (cut both P and y). So it’s screwed.

Fans of Herold Demsetz will recognize in the Fallacy of the Phantom Instrument a special case of the Nirvana Fallacy (aka the “Perfect Solution Fallacy”), that is, “The view that presents the relevant choice as between an ideal norm and an existing ‘imperfect’ institutional arrangement” rather than one “between alternative real institutional arrangements.”

The Fallacy of the Fictitious Losses

It’s at least conceivable that, despite the above arguments, NGDP targeting would still be inferior to some alternatives, because the “true” quadratic loss function, instead of being “balanced,” assigns a greater weight to inflation than to output (or employment) gaps. In that case, enduring larger or more frequent output gaps may well be a price worth paying for the sake of avoiding losses caused by letting inflation deviate from its assigned target.

But can such relative weights make sense? It’s here that the Fallacy of the Fictitious Losses comes into play. That fallacy consists of calling something a policy “loss” when incurring it keeps real variables at their desired levels, while avoiding it does not.

Economists are taught, for good reason, to treat people’s well-being, or their “utility,” as a function of real variables only. The behavior of a nominal variable, like the inflation rate, is supposed to matter only insofar as that behavior influences real variables. According to this perspective, variations in the rate of inflation are bad, not in themselves, but because they can cause undesirable changes in real variables like output, employment, and consumption. Obviously, when a central bank can avoid an undesirable change in real variables by keeping inflation stable, its failure to do so is costly, and it makes sense to call that cost a “loss.”

But when, as in the case of the adverse supply shock considered above, letting the inflation rate change is itself the only way to avoid undesirable changes in real variables, it makes little sense to treat the inflation rate change, as opposed to the adverse supply shock itself, as a bad thing, let alone to favor a policy, like strict inflation targeting, that would avoid the change only by causing undesirable changes in real economic activity.

This drawback of strict inflation targeting is, as Professor Svensson himself acknowledges with reference to a statement by Ben Bernanke, also a drawback of price-level targeting. A central bank, “cannot ‘look through’ shocks to the Phillips curve (‘cost-push’ shocks) that temporarily drive up inflation, but must commit to tightening policy in order to reverse the effects of the shocks on the price level.” Price-level targeting may therefore call for “possibly painful tightening even as the supply shock depresses employment and output.”

Precisely. It shouldn’t be necessary to add that such painful tightening is hardly likely to be worth it, and especially considering that it’s long-run price stability only that really matters to investors. James Tobin had a reason, after all, for saying that “it takes a heap of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap.”*

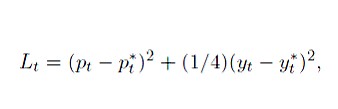

In fact, all the popular alternatives to NGDP targeting differ from it by keeping inflation closer to its target at the cost of somewhat greater deviations of output from its sustainable level. Consider flexible price-level targeting. According to Professor Svensson, were the Fed to practice it, and assuming an Okun coefficient of 2 (meaning that for every 1 percent increase in unemployment real output declines by 2 percent) its implied loss function would be

implying “a relative weight on stabilizing the GDP gap equal to 1/4.” That means that, instead of considering avoiding output (and implied unemployment) gaps more important than keeping inflation on target, a price-level targeting Fed would consider a relatively large output gap a price well-worth paying for the sake of keeping the inflation rate stable.

This brings us back to Professor Svensson’s suggestion that those who favor NGDP targeting treat it as an end in itself, rather than as potentially flawed means for achieving more fundamental macroeconomic goals. It seems to me rather that the shoe is on the other foot: it’s those who regard a perfectly stable inflation rate or price level as desirable ends in themselves who are forgetting what really matters. If some alternatives to NGDP targeting seem less costly, it’s only because of flawed accounting that treats all deviations of inflation from its target, including those that are essential to keeping output and employment at their potential levels, as “losses.”

Our Elastic Dual Mandate

Whatever its microeconomic merits, the treatment of all fluctuations in the rate of inflation as losses can be understood as a way of formalizing the dual mandate’s “stable prices” component, and that’s clearly Professor Svensson’s understanding. According to this view, even if it wouldn’t have undesirable real consequences, NGDP targeting falls short of other targeting strategies in being less consistent with the dual mandate.

But does the dual mandate’s “stable prices” really favor those other policies? Surely the most straightforward understanding of “stable prices” equates it not with a stable inflation rate, but with a constant long-run price level. Understood that way, the mandate would rule out, not just NGDP targeting, but all of the alternatives to strict inflation targeting that Professor Svensson considers. Most obviously it would rule out strict inflation, which, as Professor Svensson himself recognizes, not only substitutes a 2 percent inflation target for a constant price level, but allows the price level to “behave like a random walk with drift.” “It is a bit ironic,” Professor Svensson observes, “that inflation targeting with a low inflation target is widely referred to as ‘price stability.’ ‘Low inflation’ might be a more appropriate name.”

Indeed. Yet no one in Congress has as yet accused the Fed of failing to uphold the dual mandate’s “stable prices” provision. If the present low inflation policy satisfies that mandate, surely any reasonable NGDP targeting scheme, and particularly NGDP level targeting (which, like price-level targeting, rules out a randomly drifting price level), would also satisfy it.

Conclusion

Besides claiming that NGDP targeting is flawed in theory, Professor Svensson notes that it is difficult to implement in practice. It’s not my purpose to address those practical challenges. Instead, I highly recommend David Beckworth’s recent piece addressing many of them. My only concern here is with NGDP’s supposed theoretical shortcomings.

I don’t suppose that everyone will find my attempt to rescue NGDP targeting from Professor Svensson’s criticisms compelling. Perhaps very few will. To them, I’d like to propose a challenge. Instead of criticizing NGDP targeting in abstract terms, present a reasonable scenario in which such targeting leads to undesirable results, and in which some alternative to NGDP targeting is clearly better, not according to an ad-hoc loss function, but when judged solely by its real consequences. Doing that will really give fans of NGDP targeting, myself included, something to chew on.

________________

*Some will be tempted to respond that a predictable inflation rate itself contributes to real well-being by facilitating investment. But inflation targeting itself tends, as noted above, to result in a price level that resembles a random walk with drift. Price-level targeting is to this extent preferable. In the absence of supply shocks, such targeting is equivalent to NGDP level targeting. However, in the presence of supply-shocks, such price-level targeting makes not only expected revenues but factor prices less stable and predictable than they would be under NGDP level targeting. How this would aid rather than hinder investment is anything but clear.