A recent paper by David Autor of MIT, Lawrence Katz of Harvard and others, “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms,” begins by posing a mystery: “The fall of labor’s share of GDP in the United States and many other countries in recent decades is well documented but its causes remain uncertain.” They construct a model to blame it on U.S. businesses that are too successful with consumers.

Five broad industries, they found, became more dominated by fewer firms between 1982 and 2012: retailing, finance, wholesaling, manufacturing and services. But those aren’t industries at all, much less relevant markets: they’re gigantic, diverse sectors. Is all manufacturing becoming monopolized? Really? Census data ignores imports, but why ruin this bad story with good facts.

Noah Smith at Bloomberg ran an audacious headline about this tenuous paper: “Monopolies drive down labor’s share of GDP.” Smith writes that, “The division of the economy into labor and capital is one place where Karl Marx has left an enduring legacy on the economics profession.” He goes on to claim that “at least since 2000 — and possibly since the 1970s — capital has been taking steadily more of the pie.” Yet, Jason Furman and Peter Orszag found “the decline in the labor share of income is not due to an increase in the share of income going to productive capital—which has largely been stable—but instead is due to the increased share of income going to housing capital.” Depreciation and government, they noted, also gained an increased share (i.e., grew faster than labor income.)

President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, under Jason Furman, nonetheless worried that the 50 [!] largest firms in just 10 “industries” (if you can imagine retailing and real estate to be industries) had a larger share of sales in 2012 than in 1997 (using Census data that excludes imports). They concluded that, “many industries may be becoming more concentrated.” Noah Smith, Paul Krugman and many others have suggested that this nebulous “concentration” allowed monopoly profits to rise at the expense of the working class, supposedly explaining labor’s falling share of GDP during the high-tech boom. A quixotic search for even one actual example of monopoly soon morphed into advice about using unconstrained antitrust to constrain Amazon, which is apparently feared to have monopoly profits invisible to the rest of us.

Research that starts with such a meaningless question as “labor’s share of GDP” was never likely to lead us to any profound answers. Workers do not receive shares of GDP – they receive shares of personal or household income.

Contrary to popular confusion, dividing employee compensation (wages and benefits) by GDP does not measure how a capitalist private economy (e.g., “superstar firms”) divides income between labor and capital. Most obviously, the government makes up a huge share of GDP, including nonmarket goods like defense and public schools. Nonprofits also account for a lot of GDP, with no obvious payout to labor or capital. Less obviously, depreciation makes up another huge share of GDP, including wear and tear on public highways and bridges as well as private equipment, homes, and buildings. The “imputed rent on owner-occupied homes” is another large piece of GDP. Asking if labor is getting a fair share of defense, depreciation and imputed rent is a truly foolish question. Net private factor income would be a better gauge than GDP, for the purpose at hand, but still flawed.

The ratio of compensation to GDP uses the wrong numerator as well as an untenable denominator. Labor income must add the labor of self-employed proprietors.

When people say “labor’s share is falling,” they surely mean income people receive from work has not kept up with income people (often the same people) receive from property: dividends, interest, and rent. But, that crude Piketty-Marx labor/capital dichotomy ignores another increasingly important source of personal income: namely, government transfer payments from taxpayers to those entitled to cash and in-kind benefits.

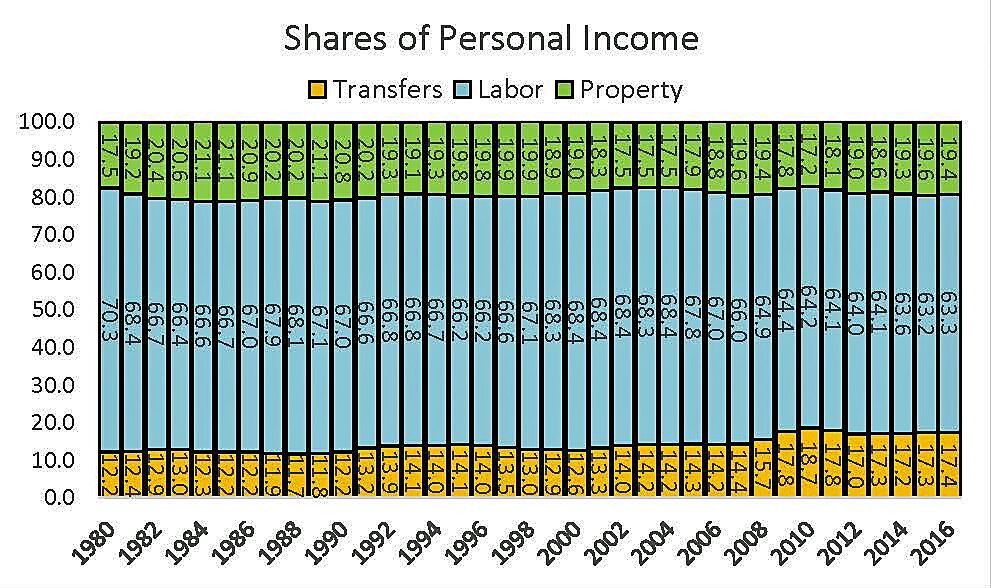

The first graph shows shares of income from labor, property, and transfers. The property share peaked at 21.1% in 1984–85, as the Fed kept interest rates very high, but averaged 19.3% and was 19.4% in 2016 (after dropping to 17.8% in 2009). The labor share averaged 66.5% but was 63.3% in 2016 even though property owners’ share was virtually flat. What went up? Transfer payments. Transfers rose from 11.7% of personal income in 1988 to 17.4% in 2016. Personal income that has been growing persistently faster than income from work has not been income from property (since the 1980s), but income from Social Security, Disability, Medicare, Medicaid, EITC, TANF, SNAP, SSI, UI, and so on.

Some might object that personal income leaves out retained corporate profits. But profits not paid out as dividends add to people’s income only if they are reinvested wisely enough to lift the value of the firm and thus generate capital gains. Personal income excludes capital gains because national income statistics measure flows of income from current production, not asset sales. That is also true of GDP, adding another reason to discard GDP as the basis of comparison.

However, Congressional Budget Office reports on the distribution of income do include realized capital gains when assets are sold (turning wealth into income).

The second graph shows that labor’s share of household income is highest in deep recessions (77.5% in 1982, 76.2% in 2009) and lowest at cyclical peaks (70.6% in 2000, 68.3% in 2007). The higher labor share in recessions does not mean recessions are good for workers, of course, but that they are even worse for business and investors. Those who equate a higher labor share of income (e.g., during recessions) with higher real income for workers are making a basic and very large mistake.

Capital income was highest in the early 1980s because the Federal Reserve kept interest rates very high, and capital income (dividends, interest, and rent) has shown no upward trend since then. Dividends and rent are up, but interest income is down.

Capital gains rose at specific times, but there has been no upward trend. There was a spike in capital gains in 1986 because the tax on gains jumped to 28% the following year. Realized gains also rose for four years after the capital gains tax was brought back down to 20% in 1997, and again after the capital gains tax was cut to 15% in mid-2003.

The white space at the top is important because it increases by four percentage points from 1990 (15.3%) to 2016 (20.3%) while labor’s share fell by 2.5 percentage points (from 75% to 72.5%). That white space is transfer payments: income from neither labor or capital. As the first graph showed, labor’s somewhat smaller share of income is not because of any sustained rise of capital income or capital gains. It is because of a sustained rise in the share of income from transfer payments and a sustained fall in the labor force participation rate.

Meanwhile, household income from owning a closely-held private business doubled since 1986: from 4% of household income in 1986 to 8% in 2013. That reflects the well-known shift of income from corporate to “pass-through” entities after 1986 as the top individual tax rate became even lower than the corporate tax rate (1988–92) or about the same dropped to the same as the corporate rate (35% 2003–2012)) or lower. That did not mean that “business” grabbed a bigger share at the expense of “labor,” but that a larger share of business income shifted from corporate to personal data.

The frequently repeated angst about “the fall of labor’s share of GDP in the United States” is based on a serious yet elementary misunderstanding of both labor income and GDP. “Labor’s share of GDP” is fundamentally nonsensical, because so much of GDP (depreciation, defense, etc.) could not possibly be paid to workers, and because the measure of labor income is too narrow (excluding the self-employed).

Labor’s share of the CBO’s broadly-defined household income also fell (unevenly) because the share devoted to transfers rose, but also because the share moved from corporate to household accounts (and individual tax returns) also rose. Business income counted within CBO’s household income has increased its share of such income since the Tax Reform Act of 1986, but that just reflects a change in organizational form from C‑Corporation to pass-through status.

Labor’s share of personal income fell mainly because the share devoted to government transfer payments rose. Labor’s share of GDP fell for other reasons (rising shares going to housing, government, and depreciation), but it is a fundamentally misconstrued statistic used to rationalize irresponsible remedies to an illusory problem of “monopolies.”