Criticizing my recent post-mortem on King v. Burwell, Scott Lemieux kindly calls me “ObamaCare’s fiercest critic” for my role in that ObamaCare case. Other words he associates with my role include “defiant,” “ludicrous,” “farcical,” “dumber,” “snake oil,” “ludicrous” (again), “irrational,” “aggressive,” “comically transparent,” and “dishonest.”

Somewhere amid the deluge, Lemieux reaches his main claim, which is that (somehow) I admitted: “the King lawsuit wasn’t designed to uphold the statute passed by Congress in 2010. It was intended to ‘enfranchise’ the people who voted against the bill.” I’m not quite sure what Lemieux means. But perhaps Lemieux doesn’t understand my point about how the Supreme Court helped President Obama disenfranchise his political opponents.

As all nine Supreme Court justices acknowledged in King, “the most natural reading of the pertinent statutory phrase” is that Congress authorized the Affordable Care Act’s premium subsidies, employer mandate, and (to a large extent) individual mandate only in states that agreed to establish a health-insurance “Exchange.” That is, all nine justices agreed that the plain meaning of the operative statutory language allows states to veto key provisions of the ACA—sort of like the Medicaid veto that has existed for 50 years and lets states destroy health insurance for millions of poor Americans. The Exchange veto includes the power to shield millions of state residents from the ACA’s least-popular provisions: the individual mandate and the employer mandate.

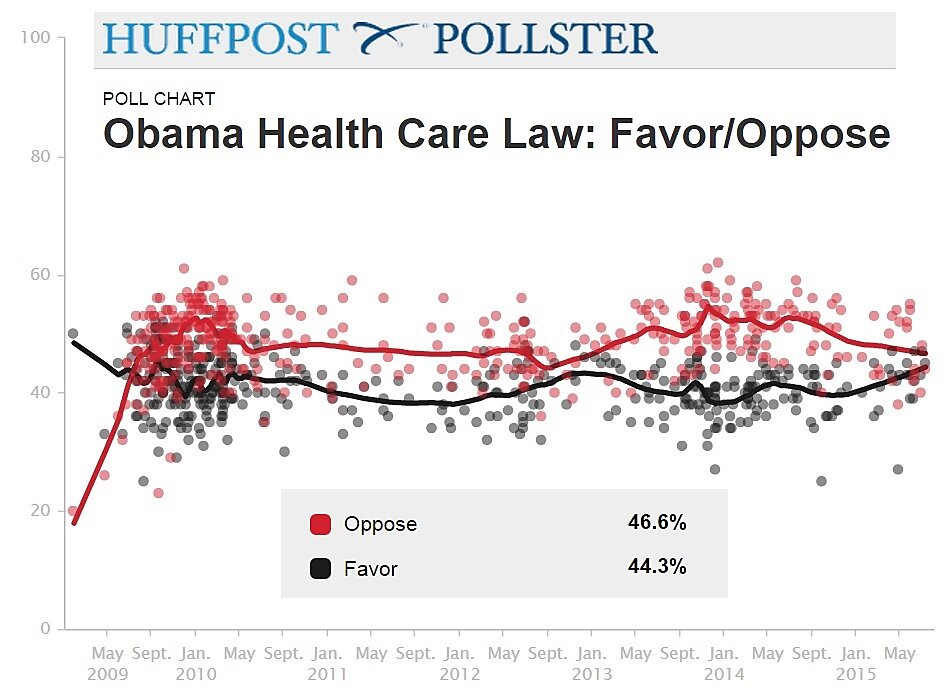

When 34 states exercised those vetoes by refusing to establish Exchanges, it was a repudiation of the ACA, driven by voters who elected ACA opponents to statewide offices in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012. In the 2010 elections, the first to be held after President Obama signed the ACA, Republicans netted control of six governorships, 22 state legislative chambers, and took outright control of more state legislatures than they had since 1952. During 2012, when states had to make the crucial decision about whether to establish an Exchange, Republicans controlled 29 governorships, two legislative chambers (and thus the entire legislature) in 26 states, and one legislative chamber in a further five states. That doesn’t even include Nebraska’s legislature, which is unicameral, non-partisan, and also refused to establish an Exchange. Public opposition to the ACA was a major—if not the major—factor in these gains, as well as GOP gains in Congress. This should not be surprising, given the ACA’s instant and enduring unpopularity.

So when President Obama chose to implement those subsidies and mandates in states that refused to establish Exchanges, he wasn’t just exceeding the powers Congress granted him under the ACA. He wasn’t just imposing taxes and spending money directly contrary to “the most natural reading of the pertinent statutory phrase.” He was actively disempowering his political opponents in the states by stripping state officials of a veto that “the most natural reading of the pertinent statutory phrase” granted them. He disenfranchised Republican and independent voters—individual Americans who put those state officials into office—by taking away the effect of their votes.

And when the Supreme Court strained to reach its counter-textual King ruling, it did not merely ratify these never-authorized taxes and entitlements. It also ratified the president’s sweeping attempt to disenfranchise his political opponents. Nixon had nothing on these guys.

In the face of the disenfranchisement of millions of voters for partisan advantage, Lemieux responds with hand-waving: “Allegedly, single special elections in 2009 and 2011 are supposed to be decisive repudiations of the Affordable Care Act.” I honestly don’t know what he’s talking about. The relevant 2009 and 2011 elections were for state offices in New Jersey and Virginia, and were not special elections. The only special election that really bears on any of this was Scott Brown’s special election to the U.S. Senate from Massachusetts—also a repudiation of the ACA—and that was in January 2010.

Lemieux claims the 2012 presidential race is a more accurate reflection of the demos than pesky state and congressional elections anyway, because “the man who signed the ACA [got] nearly five million more votes than his opponent.” That’s true, but it hardly means what Lemieux implies. Since the president’s opponent had supported an identical law while governor of Massachusetts, but then distanced himself from it, one could as credibly claim the voters would have preferred an ObamaCare opponent, but barring that they preferred sincerity to opportunism. That interpretation would be fortified by the fact that those same voters have consistently opposed the ACA, and elected a Congress (it’s a law-making body) devoted to repealing it.

As the high concentration of colorful descriptors in Lemieux’s blog post suggests, it could stand even more debunking. But I’ll leave off here to see if he and I can at least agree on where we disagree.