If you are a Baltimore resident there is a chance that over the next few months you will notice a small airplane circling above. Once you learn that it is a surveillance plane used to aid Baltimore police you might wonder how such persistent and warrantless surveillance is constitutional. After all, the Fourth Amendment of the Bill of Rights protects us from “unreasonable” searches and seizures. What could be more unreasonable that the warrantless use of an eye in the sky to snoop on hundreds of thousands of law abiding residents? The recent ruling from a Maryland district court allowing such surveillance helps highlight the sorry state of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, which is of especially pronounced concern at a time when aerial surveillance – both manned and unmanned – is becoming increasingly intrusive.

Persistent aerial surveillance over Baltimore is not new. A few years ago, the unambiguously named company Persistent Surveillance Systems (PSS) began flying its technology over Baltimore. It has also conducted flights over Dayton, Ohio; Compton, California; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. PSS uses technology originally used in Iraq, part of a regrettable trend of military gear making its way from foreign war zones to American police departments. The cameras used by PSS allow analysts to access what PSS founder Ross McNutt describes as “Google Earth with TiVo” over an area of about 32 square miles. Analysts can track people and cars, identifying where suspects travelled before and after alleged crimes.

News that Baltimore police had been using PSS technology without key Baltimore officials (including the mayor and city council members) being informed caused uproar. Nonetheless, police in Baltimore are keen on using the technology, which is being bankrolled by non-profit run by the billionaire couple Laura and John Arnold. During the pilot PSS technology will be integrated with Baltimore police ground-level cameras and gun shot detection tools.

In a bid to halt the surveillance, the grassroots organization Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle and a couple of activists argued that the use of warrantless aerial surveillance technology violated the First and Fourth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. U.S. District Judge Richard Bennett denial of their motion outlines a number of issues with current Fourth Amendment jurisprudence while also showing that the most recent prominent Fourth Amendment case decided by the Supreme Court is not as helpful as many civil libertarians had hoped.

Judges base their decisions on what constitutes a Fourth Amendment search by considering whether government action violated a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” The two-pronged reasonable expectation of privacy test, which Justice Harlan codified in his solo concurrence in the 1967 case Katz. v. United States, requires judges to consider whether government action 1) violated a subjective expectation of privacy, and if so 2) whether such a expectation is one society as a whole is prepared to accept as reasonable. If government action satisfies the reasonable expectation of privacy test it is a Fourth Amendment “search.”

Judge Bennett correctly notes in his opinion that the Supreme Court held in three cases in the 1980s (Dow Chemical Co. v. United States, California v. Ciraolo, and Florida v. Riley) that the warrantless surveillance of property from the air does not constitute a Fourth Amendment search. According to the Supreme Court, you do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the content of your private property observed from the air.

Indeed, the Baltimore Police Department’s memorandum on the constitutionality of PSS surveillance correctly noted Supreme Court precedent:

“Here, like in Ciraolo, Dow Chemical, and Riley, the photographs taken from a manned aircraft flying within publicly navigable airspace do not constitute a search, and do not run afoul of the Constitution.”

Judge Bennett goes on to discuss Carpenter v. United States (2018), the most significant Fourth Amendment Supreme Court decision in recent years. In Carpenter, the Supreme Court held that the warrantless use of cell-site location information (CSLI) to track a suspect for seven days violated the Fourth Amendment. The holding in Carpenter is a narrow one, with the majority written by Chief Justice Roberts noting: “This decision is narrow. It does not express a view on matters not before the Court; does not disturb [the Third Party Doctrine] or call into question conventional surveillance techniques and tools, such as security cameras.”

Although a major case, it’s clear that Carpenter is not a case that privacy activists should rely on when it comes to challenging all persistent surveillance tools. Judge Bennett correctly writes in his opinion that the Supreme Court’s narrow holding in Carpenter does not implicate PSS surveillance.

That the Supreme Court has not reassessed its 1980s aerial surveillance cases does not mean that warrantless and persistent aerial surveillance cannot be stopped. A number of states have taken steps to implement warrant requirements for drone surveillance, and there is no reason why Maryland lawmakers could not take steps to impose limits on manned and unmanned persistent aerial surveillance.

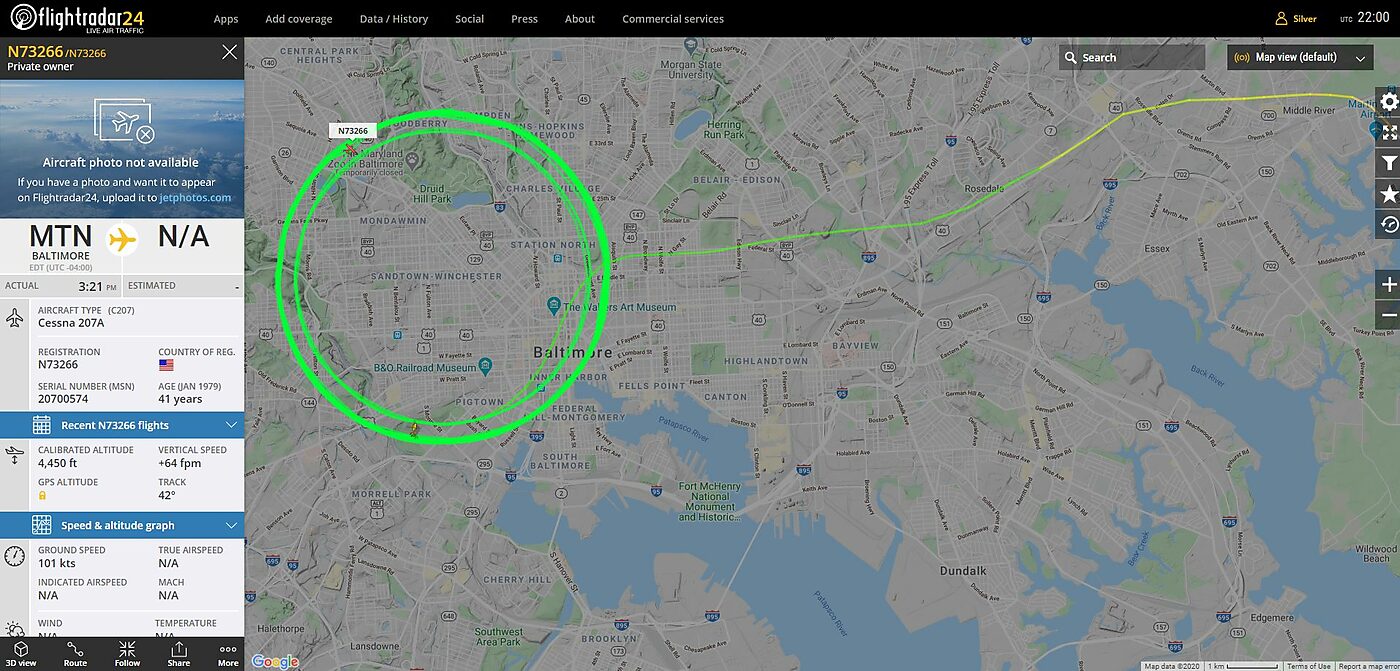

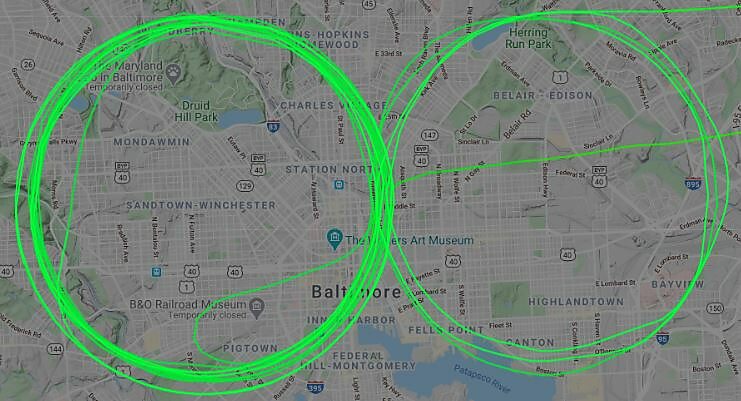

Flights paths like those below, which show recent PSS surveillance flights, should send chills down the spine of anyone who values civil liberties. It is not good enough for PSS defenders to argue that only wrongdoers need be worried. This kind of surveillance risks stifling valuable and legal activities such as protests and religious gatherings. It would not be unreasonable for many Baltimore residents to second-guess attending a protest if they know a PSS plane may be flying overhead. Members of some religious communities could also be forgiven for similar hesitance.

Aerial surveillance tools are becoming increasingly powerful. PSS cameras may not be able to identify individuals, who show up as blurs in PSS images, but we know that more powerful aerial surveillance cameras exist. It is true that the most intrusive of these cameras have been used by the military abroad, but we should be prepared for local police to deploy such technology as it becomes cheaper. Customs and Border Protection already uses drones originally designed for military missions, and we know that police departments across the country have demonstrated an unrestrained enthusiasm for using military equipment at home.

Until the Supreme Court reconsiders aerial surveillance it’s up to lawmakers to consider restrictions on persistent aerial surveillance. Unfortunately, too many lawmakers seem content with police using technology originally deployed in foreign wars.