When pressed to justify the Jones Act’s requirement that vessels used in domestic commerce be built in U.S. shipyards, supporters of the law often insist the measure is needed to ensure a robust defense industrial base. Absent the requirement, some supporters claim, the United States would find itself bereft of large shipyards vital to meeting U.S. national security needs.

Such arguments should be taken with a big grain of salt.

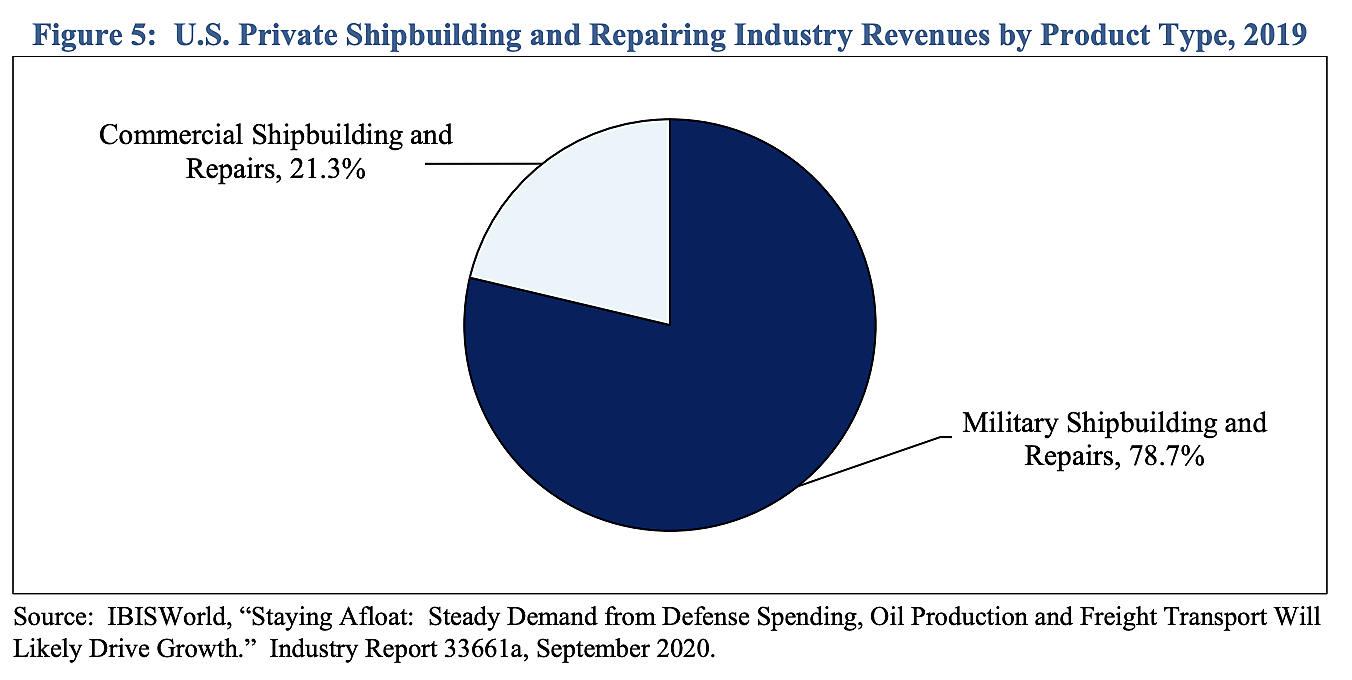

As two new government reports make clear, what’s keeping these shipyards afloat is not the construction of commercial Jones Act ships but orders from Uncle Sam. The first of these reports, from the U.S. Maritime Administration, shows that military shipbuilding and repairs accounted for nearly 80 percent of industry revenue in 2019:

Notably, Jones Act ship construction is only a subset of commercial revenue which also includes repair services not subject to the law (indeed, some Jones Act vessels make use of Chinese shipyards for repairs and maintenance). Furthermore, of the commercial vessels that are built, few are the deep-draft, oceangoing ships that help sustain large shipyards. As the report points out, “nearly all deliveries of large deep-draft vessels (14 of 15) [in 2019] were to U.S. government agencies.”

This isn’t an anomaly. The Maritime Administration’s last report examining U.S. shipbuilding, released in 2015, noted that 10 of 12 large deep-draft vessels delivered the previous year were to government agencies. Such figures comport with government data showing an average of just 3 large Jones Act ships being collectively built by the country’s shipyards per year from 2000–2019 (and this decade’s output will almost certainly be lower).

Heavy reliance on government contracts is further confirmed by yet another recent report from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Taking statistical measurements of the country’s marine economy, the report placed the value-added of U.S. shipbuilding (which does not include smaller vessels such as tugboats or those used on inland waterways) in 2019 at $11.85 billion (in 2014 dollars). Of that, “military ships” accounted for $11.551 billion, or 97.4 percent of the total.

Measuring by gross output tells a similar tale. Of the estimated $27.795 billion in shipbuilding output, military ships comprised $27.058 billion (97.3 percent). The data reveals a consistent theme, with the output percentage regularly exceeding 90 percent in the five years prior to 2019.

The more that careful scrutiny of the Jones Act’s U.S.-built requirement is applied, the less sense it makes. By forcing the use of domestically-constructed vessels that cost 4–5 times more than those built abroad, it means a smaller fleet. And the ships that do exist are older and less capable than would otherwise be the case, with the high expense of new vessels serving as a significant deterrent to fleet modernization. All in exchange for a paltry amount of commercial shipbuilding. This is an awful trade-off, both for the country’s economic prosperity and its national security.