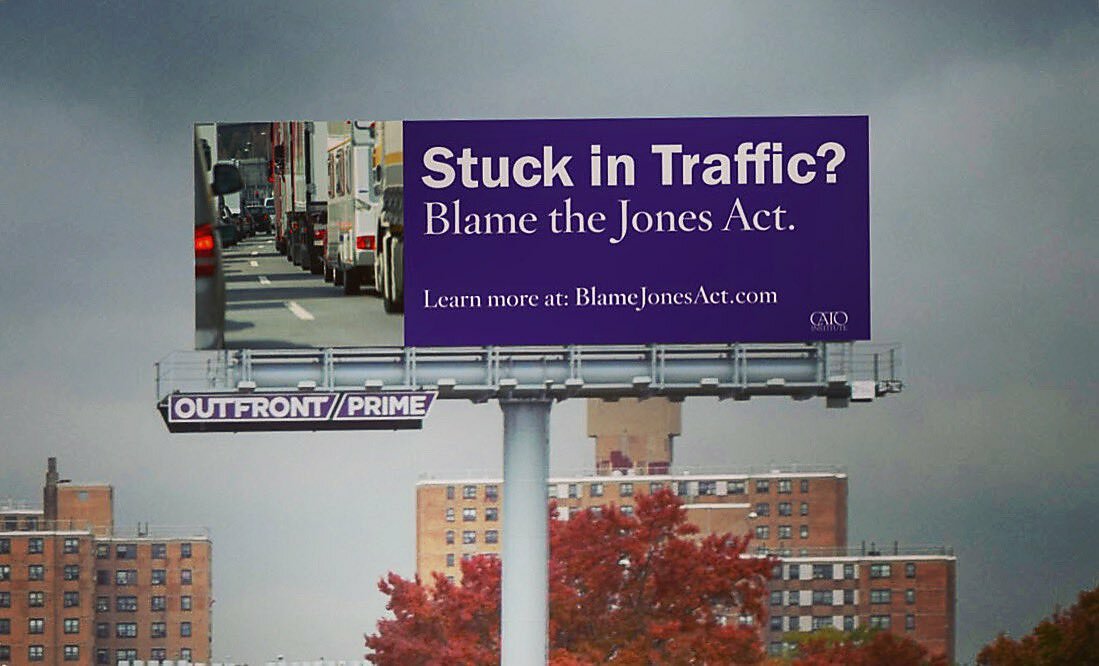

The Northeast United States is choking on traffic. According to data analysis firm INRIX, the region is home to six of the ten most congested roads in the United States as well as two of the five most congested cities in the world (New York City and Boston). That’s an obvious problem for motorists trying to get to work (or anywhere else) as well as truckers hauling freight through the region. But this raises a question: why not instead move freight using more efficient, more environmentally-friendly ships plying the coastal waters that parallel I‑95? The answer is largely found in the protectionist Jones Act, a 1920 law that restricts domestic waterborne commerce to vessels that are U.S.-registered, U.S.-built, and mostly U.S.-owned and crewed.

As an article in the Connecticut Post points out earlier this week, the lack of coastal shipping to bypass gridlocked highways isn’t for a lack of trying. Maritime industry veterans Per Heidenreich and Bob Kunkel went so far as to design a roll-on/roll-off ship for exactly that purpose, envisioning a fleet of four such vessels that would sail up and down the East Coast. The cost of building such a ship in the United States to comply with the Jones Act, however, proved fatal to the idea.

Heidenreich along with Bob Kunkel designed what they called a “compact RO-RO,” a low-emission ship that could carry 80 trailers at a time. The plan was to build four of them together carrying about 400 trailers or more a week up and down the coast.

“It would make a significant impact on the traffic and congestion that was on I‑95,” Kunkel said.

The Jones Act made that plan moot. The compact RO-RO would have cost $65 million to build in Europe at the time but double that in the United States. Because of the Jones Act, Kunkel and Heidenriech could not use foreign-built boats, and the increased cost made the plan cost-prohibitive.

“So that killed the whole project completely,” Heidenriech said. “If you allow for import of ships today, over the next 15 years, you will see 500 foreign ships owned by Americans under a U.S. flag with U.S. crews going up and down all the coasts of the United States. There’s no more economical way of transporting goods containers than ships.”

It’s a classic case of Jones Act-induced dysfunction. Facing an extra $260 million in capital costs (which could not be easily recouped if the company folded given dim odds of finding a domestic buyer and the vessels’ value being at least halved on the international market), the service could not be launched. That meant a missed opportunity to reduce congestion, emissions, and highway maintenance.

Ironically, it was also a blow to the very domestic maritime industry the Jones Act is ostensibly meant to promote given foregone mariner jobs and business for ports. Compounding matters, the Jones Act’s prohibition on foreign-built vessels for use in coastal shipping didn’t mean they were instead constructed in U.S. shipyards. It meant they weren’t built at all. In fact, U.S. shipyards ended up as losers in this episode through the loss of potential repair and maintenance work on the envisioned coastal vessels.

Heidenreich and Kunkel’s inability to build ships in the United States cost-effectively for use in coastal shipping is par for the course. With limited exceptions, Jones Act ships are only used (and built for) on trades such as Hawaii, Alaska, and Puerto Rico where alternative modes are not an option. Their high capital costs help ensure that competition with other forms of transport—even congested highways—simply isn’t viable. So very few ships get built here, and the domestic industry continues to decline.

Indeed, numerous sources have identified the extraordinarily high cost of domestic shipbuilding as a significant impediment to coastal shipping. A 2006 study, for example, found that shipping firms viewed such costs as the single largest obstacle to such shipping services while a 2013 study pointed to lowered vessel costs as a leading means of encouraging short sea shipping along the I‑95 corridor. Similarly, a 2005 GAO report highlighted the expense of U.S.-built ships as contributing to the start-up costs of short sea shipping services and a 2011 report prepared for the U.S. Maritime Administration highlighted the salutary effects of allowing the use of foreign-built vessels, “even if for limited periods of time.”

The verdict is clearly in.

Thus far, however, such evidence has failed to shake Congress from its love affair with the Jones Act and the special interest groups that support it. Indeed, President Biden just last night promised in his State of the Union speech to expand Jones Act-style local content mandates (“Buy America”) for public projects, including federal highways—precisely the opposite of what the government should be doing to reform U.S. transportation policy (as I explained here). So American drivers already suffering from one protectionist mistake can perhaps look forward to other ones causing even more dysfunction on our roadways.

On the bright side, they’ll have more time to learn about it while sitting in traffic.