Monopolies in business usually lead to bloated costs and high prices. As such, economists generally favor opening industries to competition in order to promote efficiency and product quality. Governments are monopolies that also tend to be bloated and inefficient, and so we should favor ways to subject them to competition also.

Cross-border competition for people, businesses, and investment dollars is one way to do it. Within the United States, people and businesses can weigh the costs and benefits of different states and cities, and freely move when they find a better deal. That creates pressure on state and local policymakers to restrain taxes and provide quality services.

National policymakers now face similar pressures as globalization has intensified over the years. To attract investment, many countries have reformed the most damaging parts of their tax codes, including cutting high marginal tax rates on corporate income. Cutting corporate tax rates would be beneficial even without globalization, but cross-border competition has nudged policymakers in the right direction.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has a different view. She recently complained about a “30-year race to the bottom” in corporate tax rates. The average corporate tax rate across OECD nations has fallen from 41 percent in 1990 to 25 percent today. But this has been a race to reduce the economic damage of corporate taxation, which in turn has promoted broad-based economic growth. As I discuss here, if workers were a lobby group defending their self-interest, they should favor slashing corporate tax rates. Workers and capital are complements in production, and more capital generally leads to higher wages.

Yellen seems to make the mistake of assuming that international tax competition is a zero-sum game. In fact, it is a positive-sum game. Reductions in corporate tax rates generate growth and expand the global economy to the benefit of all.

The race-to-the-bottom claim is off-base in another way. Yellen said, “It is important to work with other countries to end the pressures of tax competition and corporate tax base erosion,” and she wants governments to raise “sufficient revenue.” But reducing corporate tax rates tends to expand corporate tax bases, with the result that corporate tax revenues across major countries have not fallen. Average corporate income tax revenues in the OECD have risen from 2.4 percent of GDP in 1990 to 3.1 percent in 2018.

Yellen said she would work “with our allies on a global tax regime that protects American competitiveness while ensuring corporations pay their fair share.” But the corporate tax revenue share of GDP has risen, as noted. Besides, the corporate tax burden ultimately lands on individuals, so it is meaningless to talk about corporate “fair” shares.

If Yellen is concerned about fairness, she should rethink her idea of imposing a global minimum corporate tax rate. That would be an arrogant move by a big and powerful country such as the United States. The corporate income tax is an inefficient tax, and so poor countries that want to attract investment and grow should cut them. Just a few decades ago, Ireland was much poorer than Britain, but its implementation of a low corporate tax rate has helped the Emerald Isle grow strongly and surpass Britain in living standards. Yellen’s approach would unfairly deny small and poor nations the ability to adopt Ireland’s powerful reform approach.

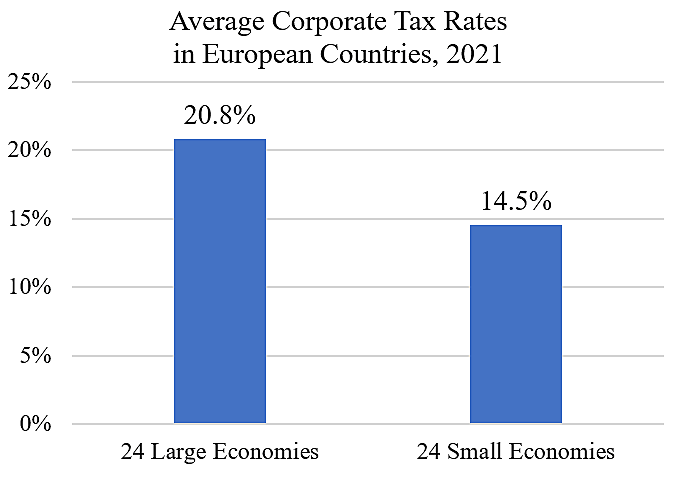

Smaller countries tend to have lower corporate tax rates because they know that they need to be welcoming to investment to compete with giants such as the United States. The chart shows average corporate tax rates for the 24 largest and 24 smallest economies in Europe, based on KPMG data. Yellen’s global minimum tax rate would undermine small-country growth prospects, and that would not be fair at all.

For background on international tax competition, see Global Tax Revolution. For the chart, 48 European countries were sorted by GDP.