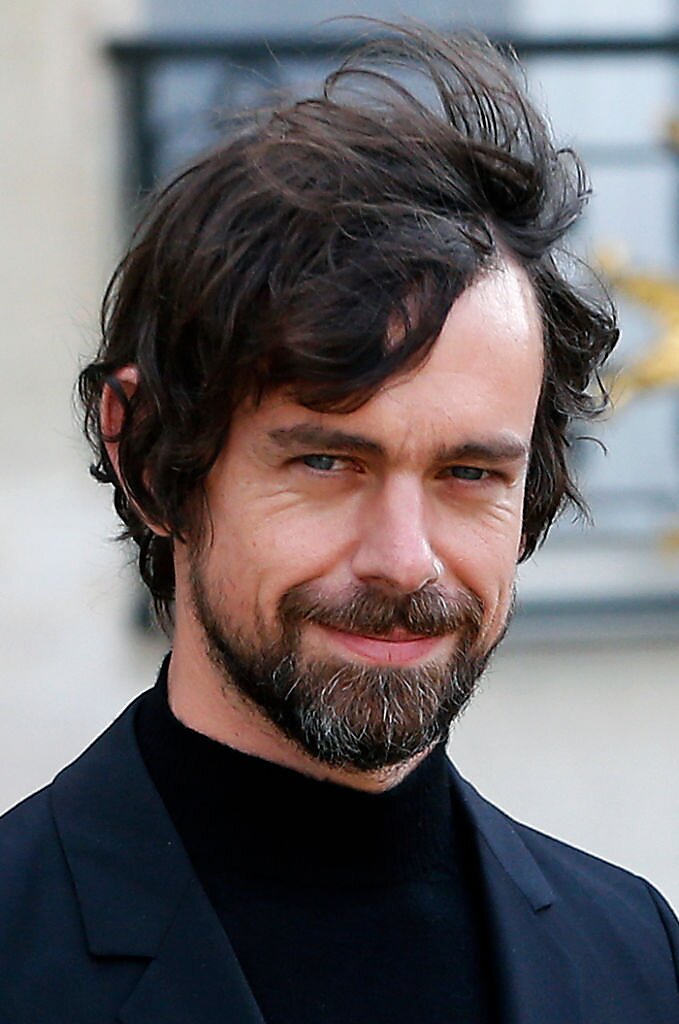

Jack Dorsey, the founder and prior leader of Twitter, now X, had a remarkable conversation on how social media companies face massive pressure from governments around the world to censor speech and expressed his hope for a decentralized future. It should serve as a reminder to policymakers that alternatives to the current social media structures are possible without government regulation. Indeed, this is one of the topics covered in my new Cato paper, A Guide to Content Moderation for Policymakers.

Jack spoke about the need for innovation and decentralization after announcing that he was leaving the board of alternative social media company Bluesky and deleting his account. Mike Solana, head of the tech media outlet Pirate Wires, discussed what happened with Jack in an interview that is worth reading in full.

Rather than recapitulate the interview, I want to note a few takeaways for policymakers and how they align with some of the observations in my new paper.

First, it is worth remembering that when the internet first exploded onto the scene, it was nearly universally lauded for the way it expanded the ability of users around the world to express themselves and access information while avoiding government censorship. It was optimistically thought that the internet couldn’t be controlled. Fast forward to today, and authoritarian nations, such as China, have their internet siloed from the rest of the world. Other nations expansively regulate the internet, making increasingly aggressive demands of large tech companies to suppress speech.

One of the reasons this is possible is because most online services are centralized, i.e. each service sets the rules and policies that govern what users can say and do on their platform, runs massive enforcement systems to uphold their policies, and determines how their platforms will offer up content and services.

But what if Facebook couldn’t delete your profile? What if YouTube simply didn’t have the ability to centrally demote or remove your content? If users, rather than platforms, were ultimately responsible for their social media experience, then governments could make demands, but companies would simply lack the technical ability to comply. Governments could decide to go all the way and drastically block certain internet services, but that would force them to reveal themselves as authoritarian censors. Plus, a decentralized network could likely avoid the block.

Jack believes this decentralized version of social media and internet services offers a censorship-resistant vision of the future. It’s an important reminder to policymakers that governments worldwide are vying for control over social media, whether it be the multitude of tech regulation and expression restrictions in the EU, a judiciary-turned-speech-police in Brazil, various government efforts in India, Australia, and elsewhere to block “problematic” content, and even informal pressure and coercion by US officials to sway content decisions—not to mention plenty of fully authoritarian states.

Those who truly want greater expression online shouldn’t join the ranks of these censors. They should instead support the power of the market and innovation to create new tools and technologies that can resist government demands

A second related observation is that even when the government isn’t twisting the arm of tech companies, these businesses are very capable of making bad and biased decisions. Whether it be botched “woke” generative AI rollouts, suppressing significant political stories at the height of an election, or crafting policies that explicitly favor one ideological viewpoint on controversial issues, such as gender, abortion, or various forms of extremism, tech companies aren’t perfect. For myriad reasons, including advertising incentives, the demands placed by outside activists, or internal structural and ideological preferences, many tech companies have increasingly found ways to limit expression and who is allowed to use their products.

To be clear, it is their right to determine the rules for their services. But that doesn’t mean it’s been beneficial for a culture of expression, fostering diverse views, or even helping their business long term. As a result of increasing restrictions on various platforms and services, there have been demands for change. Elon Musk bought Twitter, and new services like Bluesky, Rumble, Truth Social, and others have sprung up in popularity. But again, Jack notes that as long as these companies have centralized policies, there will always be pressures to moderate speech and remove users. Indeed, he left Bluesky because he felt like it was repeating the mistakes of Twitter by starting to centralize content moderation tools and the ability to remove people from the system.

So, once again, we see the value of a more decentralized social media environment. Right now, the mainstream social media companies face the moderators’ dilemma. Some folks want more content to be taken down, others want less to be suppressed, and still others want moderation done differently. With one centralized set of rules, there will always be groups lobbying tech companies to favor their group’s perspective and the companies will never be able to break out of this dilemma because they will always be accused of favoring one group and offending another.

But if users gain control over what appears in their newsfeed and how different types of content are moderated, then we’ve started to solve the problem. Those who want to see more types of controversial content can see it, while those who don’t want such content can protect themselves. It’s a customizable set of rules that each user can adopt and change at will.

A decentralized future for social media can address government censorship as well as market demands for greater expression and better experiences online. Before policymakers try to “solve” various problems and harms with social media, they should recognize that the medium is already changing and will continue to evolve and innovate—but only if government regulations don’t get in the way. Policymakers may feel that tech companies are biased against them. In some cases, this may be true. But rather than advance expression or better protect users, new government restrictions on social media companies will likely stifle the innovations that would bring about much-needed improvements.

If policymakers want to see users protected online, then they and civil society should encourage existing and new social media companies to embrace more user expression and greater user controls.