We weren’t kidding in the title to this post. There really is something called spelt milk. There is also soy milk, rice milk, coconut milk, almond milk, hemp milk, quinoa milk, oat milk (that’s not a typo — oat milk, not goat milk, although there is also goat milk of course), and pea milk (yes, really, pea milk). But now the cow milk producers are crying to the government (multiple branches, in many countries) that these non-dairy milks should not be allowed to use the term “milk.” They claim this is about consumer confusion, but are any consumers confused about where soy milk comes from? Although recent polling suggests that a few people think chocolate milk comes from brown cows (we suspect they were just having fun with the pollsters), it’s hard to believe that people purchasing these alternative milks couldn’t figure out their source. The term “milk” has been used to describe plant-based beverages for centuries, and we shouldn’t let the dairy lobby change that.

In the United States, there are efforts underway to push both the legislative and executive branches to protect dairy producers from their non-dairy competitors by keeping the word “milk” off the competitors’ products. With support from the industry, Senator Tammy Baldwin has introduced legislation that, as she puts it, “would require non-dairy products made from nuts, seeds, plants, and algae to no longer be mislabeled with dairy terms such as milk, yogurt or cheese.” But this legislative action may not even be necessary, because here’s what may be happening soon at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA):

The head of the FDA said … that the Trump administration will move to crack down on the use of the term “milk” for nondairy products like soy and almond beverages.

The agency will soon issue a guidance document outlining changes to its so-called standards of identity policies for marketing milk, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said at the POLITICO Pro Summit.“An almond doesn’t lactate, I will confess,” Gottlieb said, referring to the fact that the agency’s current standards for milk reference products from lactating animals.The move would be a major boon for dairy groups, which have been struggling amid dropping prices and global oversupply. The industry has petitioned FDA to enforce marketing standards for milk, but the agency has not previously addressed the issue.

We are not scientists, but his statement about almonds not lactating sounds right to us. But regardless of whether almonds or other plants lactate, there is a long history of using the term “milk” for plant-based products that do not lactate. Smithsonian Magazine recently put it this way: “Linguistically speaking, using ‘milk’ to refer to the ‘the white juice of certain plants’ (the second definition of milk in the Oxford American Dictionary) has a history that dates back centuries.” We didn’t check all the dictionaries, but here are a couple that illustrate the point. The online edition of Webster’s Dictionary, 1828 defines milk as:

1. A white fluid or liquor, secreted by certain glands in female animals, and drawn from the breasts for the nourishment of their young.

2. The white juice of certain plants.

3. Emulsion made by bruising seeds.

Along the same lines, the Oxford English Dictionary defines milk as:

1. An opaque white fluid rich in fat and protein, secreted by female mammals for the nourishment of their young.

‘a healthy mother will produce enough milk for her baby’

1.1 The milk from cows (or goats or sheep) as consumed by humans.

‘a glass of milk’

1.2 The white juice of certain plants.

‘coconut milk’

1.3 A creamy-textured liquid with a particular ingredient or use.

‘cleansing milk’

And the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language defines milk as:

1. A whitish liquid containing proteins, fats, lactose, and various vitamins and minerals that is produced by the mammary glands of all mature female mammals after they have given birth and serves as nourishment for their young.

2. The milk of cows, goats, or other animals, used as food by humans.

3. Any of various potable liquids resembling milk, such as coconut milk or soymilk.

4. A liquid resembling milk in consistency, such as milkweed sap or milk of magnesia.

All of these definitions include non-dairy liquid substances as examples of what can be considered milk. Thus, identifying these products as “milk” is nothing new. In fact, in examining the etymology of the word milk, it appears that “milk-like plant juices” date back to the 13th century, with some even showing up in medieval cookbooks.

The issue has also arisen outside the United States. The Codex Alimentarius Commission, an international body that develops food standards, defines milk as “the normal mammary secretion of milking animals obtained from one or more milkings without either addition to it or extraction from it, intended for consumption as liquid milk or for further processing.” However, the Codex standard for the use of dairy terms also stipulates that the restrictive use of the term “milk” for labelling of milk, milk products or composite milk products “shall not apply to the name of a product the exact nature of which is clear from traditional usage or when the name is clearly used to describe a characteristic quality of the non- milk product.” So there appears to be some flexibility in how countries apply this standard, and Codex even notes that “Plain soybean beverage is the milky liquid prepared from soybeans” and that some countries refer to soybean beverages as “soybean milk.”

So what have other countries done in regulating non-dairy milk products? It may be helpful to first take a look at the European Union’s rules, as Europeans famously tend to have fairly strict food labelling standards. Milk is no exception. In fact, this very debate played out in a European Court of Justice case in 2017, Verband Sozialer Wettbewerb eV v TofuTown.com GmbH, where German company TofuTown argued that it clearly identified its products as plant-based, and thus should not be prohibited from calling its products “Soyatoo tofu butter” or “Veggie cheese” for instance. But EU rules prohibit the use of these terms for non-dairy products, so in this case TofuTown’s descriptions of its products were found to be in violation.

At the same time, the EU rules do allow Member States to make exceptions, noting that the restrictions on marketing a product as a “milk” product “shall not apply to the designation of products the exact nature of which is clear from traditional usage and/or when the designations are clearly used to describe a characteristic quality of the product” (this language mirrors that of Codex). Notably, products such as almond milk and coconut milk are exempt, among many other common designations, such as nut butters.

Closer to home, it appears that Canada is even stricter in its approach than the EU. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency states that “Milk, unless otherwise designated, refers to cow’s milk” (though goat’s milk is ok too) and provides strict guidelines for the marketing of milk products. However, some plant-based beverages can be considered “milk product alternatives” and the Canada Food Guide, which provides information to Canadians about diet and nutrition, suggests “fortified soy beverages” as an alternative to milk. They just can’t refer to it as “milk” on the label. (The mom of one of this post’s authors has verified that her carton of almond milk doesn’t have the word milk on it anywhere—there’s some small print that reads “fortified almond beverage.” Her mom still referred to it as milk, however, suggesting that government policy may not reflect common language usage.)

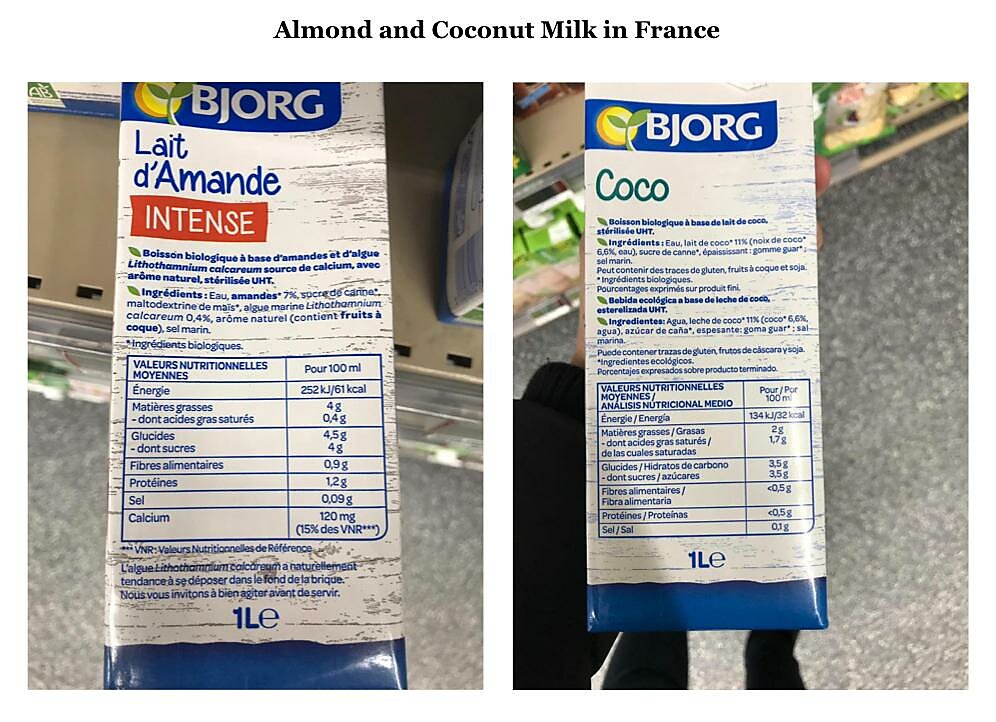

To illustrate how these products look on the shelves in the EU and Canada, we enlisted some skeptical friends and family members (who couldn’t see how this could possibly be related to our work) to take pictues:

So what’s going on in the United States, and why is Sen. Baldwin pushing the DAIRY PRIDE Act (Defending Against Imitations and Replacements of Yogurt, Milk, and Cheese To Promote Regular Intake of Dairy Everyday)? Whatever happened to American exceptionalism, and are we on our way to adopting the metric system now? Hint—the word to focus on here is “promote.” It is no secret that the U.S. dairy industry has been in decline (Americans drink 18 gallons of milk a year, compared to 30 gallons back in the 1970s), while almond milk has witnessed the opposite trend, with sales growth of 250% in the last 5 years. Taking into all the various milks, non-dairy milk has seen sales grow by 61% over the last five years.

The dairy lobby recently flexed its muscles in pushing for concessions from Canada in the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (i.e., the new NAFTA), but that’s clearly not enough for them. They’re now ramping up efforts to challenge their direct competitors, the non-dairy milk industry. While it’s not clear that changing the labelling standard would alter consumer behavior in any way, that does not mean that government intervention in this area is harmless. It uses up governing resources, and creates consumer confusion where none currently exists. Perhaps there is some small risk that Thanksgiving will be ruined when someone brings a pumpkin pie that is made with coconut milk, but we don’t think this worry merits legislative or executive action.