We hear a lot about book “banning,” especially when “we” maintain Cato’s Public Schooling Battle Map, but probably lots of other people hear it, too. Indeed, it just so happens that we are in Banned Books Week right now, an event that highlights challenges to books stocked by public libraries, including in public schools. But what is suddenly getting attention is not the Week, but a Cambridge, Massachusetts public school librarian rejecting a bunch of Dr. Seuss books that First Lady Melania Trump selected the district to win. Which raises two questions: Is it not just as much “banning” when public librarians choose not to stock books as when parents or citizens ask that those already stocked be removed? And isn’t it a threat to basic freedom to have librarians or anyone else decide for taxpayer-funded institutions—government institutions—what constitutes acceptable art or thought?

The first answer is of course it is just as much “banning” for public institutions to reject books in the first place as to remove them later on. The ultimate result is the same: not making a book available for the public to borrow. Of course, this is not really banning, which would be to prohibit people from reading a book at all—making it illegal to purchase or possess—not refusing to let people borrow it for free. But if people want to misapply the term, they should misapply it equally.

Which takes us to the root problem: Public institutions force all taxpayers to fund decisions by other people about what books are valuable, or age appropriate, or just plain morally upright. We are forcing them to fund someone else’s speech and opinions, even if they find that speech or those opinions offensive, or just wrong, and even if their views are rejected.

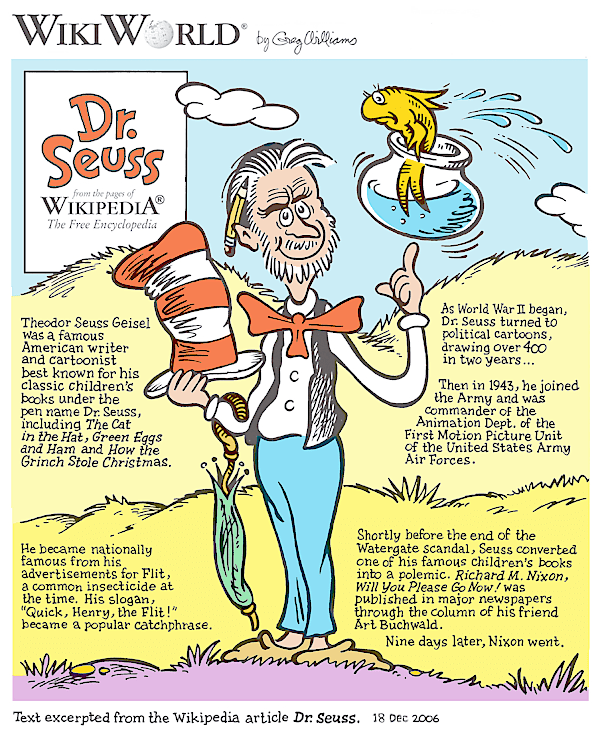

Look at the Cambridge situation. Librarian Liz Phipps Soeiro’s letter rejecting the haul of Seuss books was intensely political—itself a huge problem for someone speaking in an official capacity—but she also condemned the Seuss books themselves. “Another fact that many people are unaware of is that Dr. Seuss’s illustrations are steeped in racist propaganda, caricatures, and harmful stereotypes,” she wrote. “Open one of his books (If I Ran a Zoo or And to Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street, for example), and you’ll see the racist mockery in his art.”

Perhaps this is a unanimous opinion among people in the Cambridge school district—we know it wouldn’t be if expanded to Springfield, MA—and if so, okay. But if there is just one taxpaying dissenter who does not believe that Seuss’s work is racist, or who believes that his or her kids should grapple with racist works, or who just thinks Seuss is good literature worth reading, this person has essentially been rendered unequal under the law. He or she is forced to pay, someone else decides what is moral or appropriate.

Of course, barring the invention of infinite shelf space—actually, we call that the “Internet”—someone has to decide what is or is not stocked in libraries. At least for education, that is a reason that school choice is essential, especially through tax credit programs in which people choose whether, and for whom, to fund scholarships. With such programs no one is forced to fund or be subject to other people’s decisions about what is moral or age appropriate. It ends the government gatekeeper role, and lets no one impose a “ban” on anyone. It is exactly what justice and freedom demand.