— Bertrand Russell, Unpopular Essays

Do you have the strong sense that the United States has become a more anxious and fearful place during the Trump era? If so, you are certainly not alone. Recent news stories reveal all sorts of concerns including the fate of the Dreamers, healthcare, North Korea, and even America’s democratic norms and institutions.

But exactly how worried are we today compared to other times?

As it turns out, the answer is: quite a bit more worried.

In this blog post I introduce a simple measure called the American Fear Index. The index is an attempt to improve our understanding of fear and its role in American politics by tracking the level of fear in our public discourse about the nation, the world, and the challenges we face.

The study of fear is far from just an academic matter. Fear is a powerful political force. At times, a well-warranted fear is an important motivator of caution and prudent behavior. History provides numerous examples of publics without sufficient concern about the behavior of their government leaders. But on the other hand, fear also has the ability to cloud people’s senses, to destroy their ability to conduct rational debate, and to warp their decision-making. Fear has always been a useful tool for propagandists and zealots.

Measuring Fear: Data and Methods

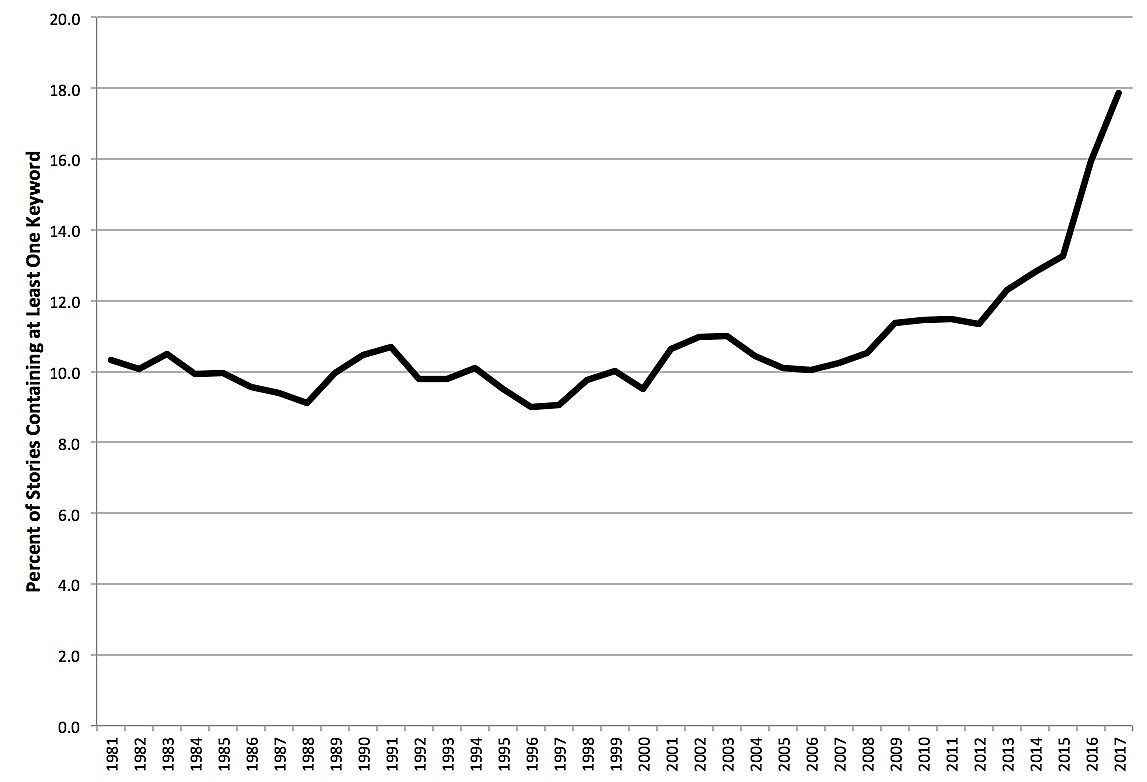

The American Fear Index (AFI) is simply the percentage of all news stories during a given time period that contain at least one of four fear-related keywords: fear, risk, danger, or threat. The choice of these words reflects the desire to identify a small set of general words that were very likely to appear in discussions of things that worry people across as broad a set of topics as possible.

Of course, not every story containing one of these words is entirely focused on fear or terrible things. And some stories contain just one of these words; in other stories the words appear many times. But a review of stories containing these words shows that the passages in which they appear do in fact tend to focus on issues and events that Americans find threatening, dangerous, risky, and scary.

Though this is an exceedingly simple and blunt approach to measuring fear, previous studies have shown the effectiveness of similar approaches at tracing complex phenomenon such economic policy uncertainty, partisan conflict, and interstate tensions. Moreover, the simplicity allows us to apply the AFI across more data and over time far more easily than more complex measures. Ideally, of course, more complex approaches should complement simpler tools like the AFI.

The universe of news stories for this analysis was a list of sixty or so of the top U.S. newspapers available in the Dow Jones Factiva “Top U.S. newspapers” database. This allows the AFI to trace the dominant themes in national discourse, which typically originate with major newspapers like the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post, while also casting a wide net encompassing the other major city and regional dailies. Though each paper has a unique AFI score across time (a topic I will address in a future post), the goal of bundling them together is to create a metric that measures fear-related discourse at the national level.

To calculate the AFI, I first ran a search using the Factiva search engine to establish how many stories were published each year since January 1, 1981. I did this by searching for the word “the,” which shows up in all (or at least almost all) stories. I then ran a search for all stories containing at least one fear keyword using the search string “fear or risk or danger or threat.” To calculate the AFI I divided the number of news stories containing a fear keyword by the total number of stories published each year, and then multiplied the result by 100.

With the general fear index measured, I then turned to topic-specific AFI levels, tracking how often the fear keywords appeared in stories that also mentioned various issues of potential concern. To produce an AFI score specific to cancer, for example, I ran a search using the search string “cancer and (fear or risk or danger or threat).”

Fear in America

Figure One displays the American Fear Index from 1981 through June 30, 2017. Two important things stand out.

First, the results provide stark support for anyone who has suspected that we are living through unusually turbulent times. Through the first eight months of 2017, 17.9% of all news stories contain at least one fear keyword, the highest level recorded in the analysis and well above the historical average of 10.8%. Making the recent spike even more interesting is just how stable the annual fear index was until recently. The index averaged 10% between 1981 and 2008, with a low of 9% in 1996 and a high of just 11% in 2002 and 2003.

Second, Trump may have poured gas on the fire of America’s recent worries, but he certainly didn’t start the fire. The fear index jumped sharply to 11.4% in 2009 as the Great Recession hit and hovered right at that level during Obama’s first administration. Since 2013, however, the index has risen each year.

Figure One. The American Fear Index 1981 — 2017

What Are Americans Afraid Of?

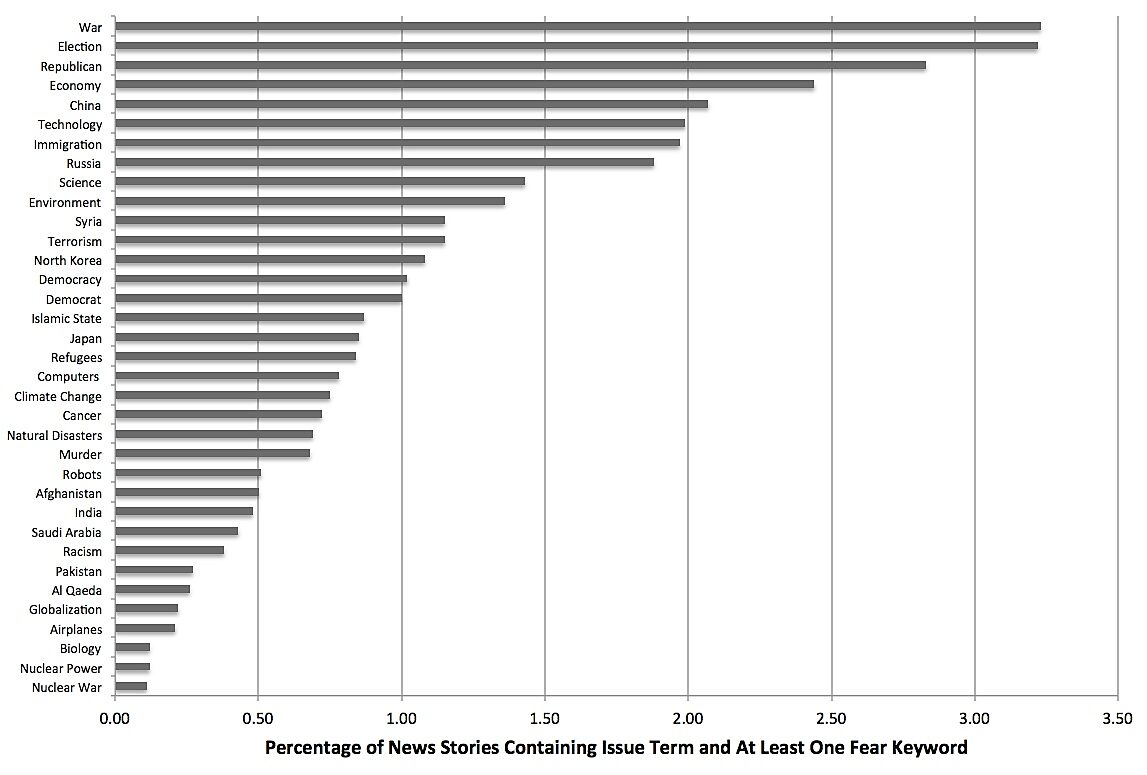

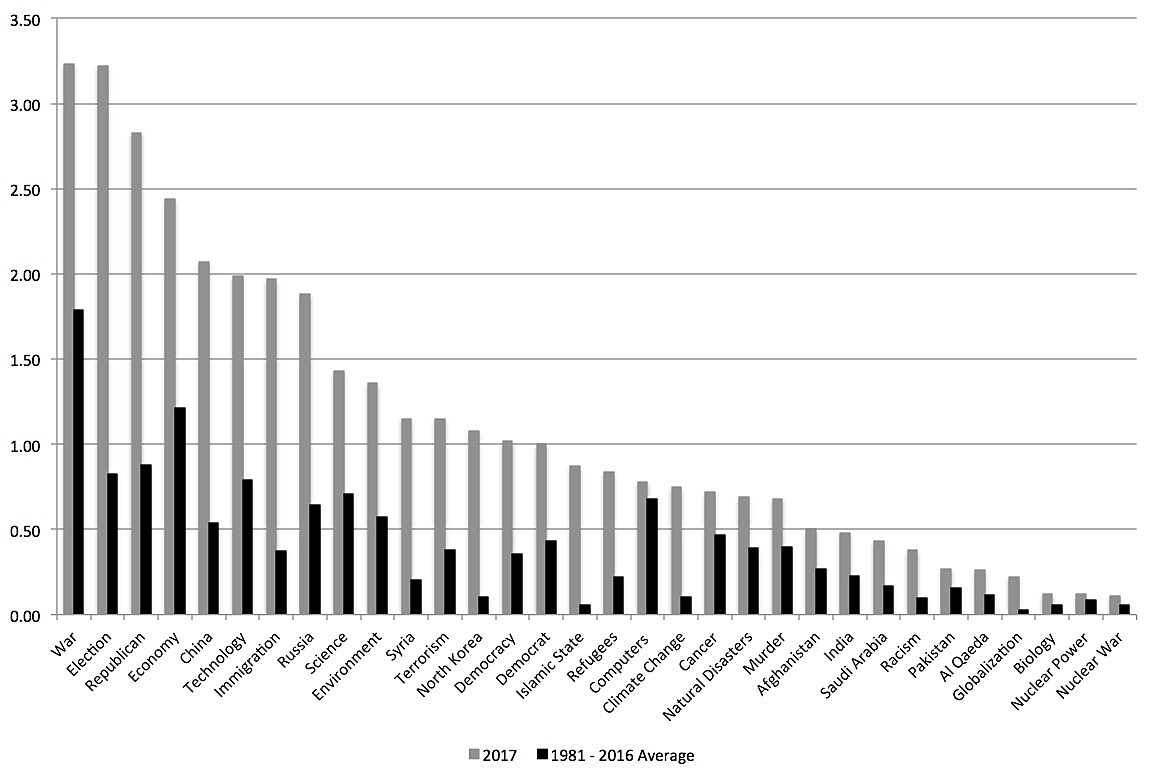

Figure Two provides a snapshot of the fear associated with a variety of issues in 2017. Though this figure by no means contains a comprehensive account of American fears, it includes many of the hot button issues of the day and a slew of perennial risks, threats, and dangers of all kinds.

Given the turbulent 2016 election campaign and the prospects for a bruising set of Congressional midterms in 2018, it is perhaps depressing but not surprising to see that the word election has been most closely associated with fear so far in 2017. Nor are most of the other top fears much of a surprise given Trump’s campaign rhetoric and initial policy decisions on issues such as Syria, North Korea, and the travel ban.

Figure Two. Snapshot of American Fears, 2017

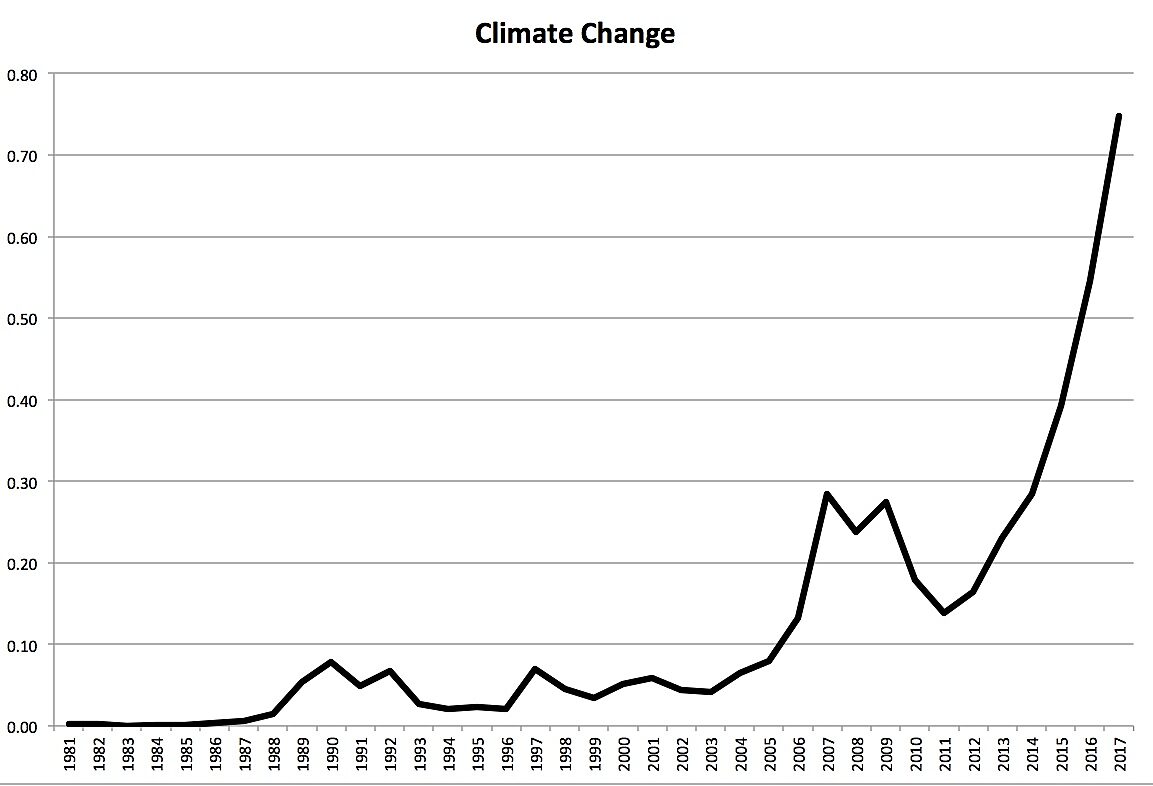

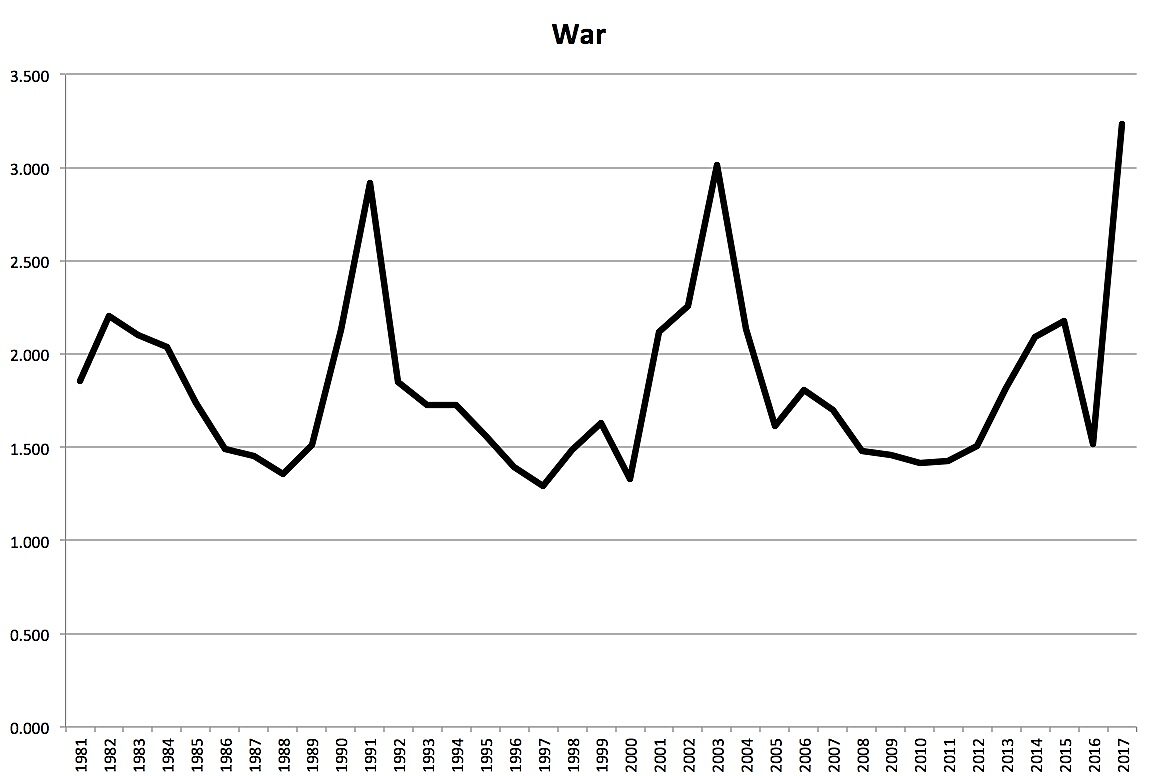

As it turns out, most fears rise and fall over time. Figure Three examines the historical evolution of three of them, chosen to illustrate just a few of the different patterns that emerge.

Figure Three: Climate Change, Murder, and War

Rising American Fears

At this point we know that American discussion of fear, risk, threat, and danger is up sharply over the past few years. We also have a sense for the relative level of anxiety across a range of important issues.

Figure Four extends the analysis to provide a sense of how much more worried Americans are in 2017 about these specific issues compared to the past. The gray columns indicate the AFI scores for 2017, while the black bars represent the average AFI score between 1981 and 2016.

Strikingly, the average AFI score for these issues in 2017 is 120% higher than in 2016 and 278% higher than the historical average. In short, the level of fear-related discourse in major American newspapers — for these specific issues – doubled between roughly 2013 and 2016, and then doubled again (plus some) between 2016 and 2017.

Figure Four. Rising Fear by Issue, 2017 vs. Historical Average

Explaining Patterns of American Fear

Fear related discourse is clearly at an all-time recent high in 2017. The big question is why. The world certainly has been exciting in 2017, but is this really about the threats facing the United States, or is it more about how Washington is addressing them? More specifically, how much of the 2017 spike in fear talk is related to Donald Trump himself?

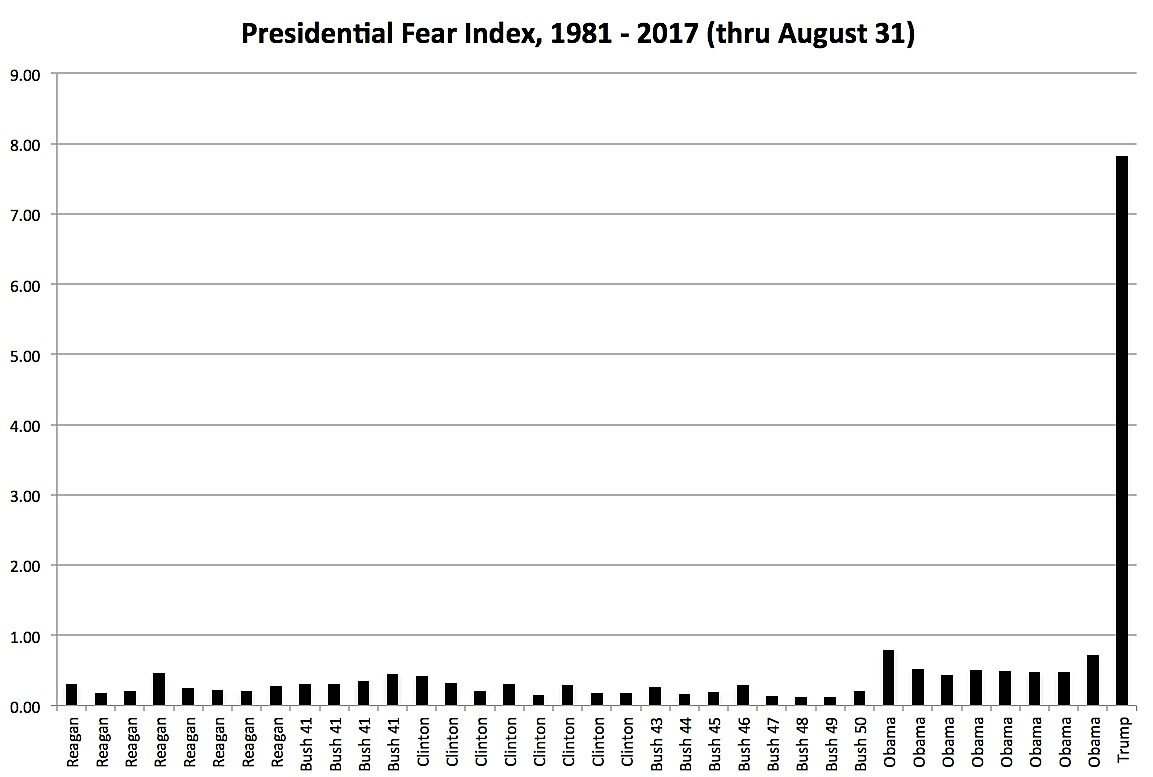

Figure Five suggests that the answer is a great deal. Trump’s 2017 fear index (7.2%) is almost 11 times higher than Obama’s highest score (0.72%). The average historical “presidential fear index” – stories mentioning both the president and at least one of the keywords – is just 0.32%.

Figure Five. Trump: Threat Inflator in Chief?

Unfortunately, this simple metric does not help us determine the extent to which Trump himself is actively inflating threats, others are blaming Trump for problems, or Trump as president is simply at the center of more fear related discourse thanks to the general craziness of the world today. The most likely case is that some of all of these things are happening, leading to Trump’s unprecedented personal fear index.

I cannot resolve that puzzle here, so for now I offer the following hypotheses to explain Trump’s elevated fear index:

- The surprise outcome of the election, combined with Russian election meddling and the pursuant investigation into the Trump campaign has generated more stories mentioning Trump and various fears

- The unprecedented opposition to Trump by both liberals and conservatives has generated more Trump related fear discourse in the news

- Trump’s decision to focus on highly controversial and fear-laden policy issues (immigration, healthcare, etc.) has inserted Trump into fear related discussions on those topics

- Trump’s controversial and clumsy foreign policy efforts that have stoked tensions abroad (North Korea, in particular), leading to news stories that mention both Trump and various international threats

- News media bias (whether a liberal bias or just a “Trump = news” bias) has led to far more coverage of Trump than other presidents and to far more negative (i.e. fear related) coverage

- Trump’s inexperience, his nontraditional and cavalier approach to governance, and the lack of discipline exhibited by his White House have raised fears about democratic institutions, leading to a higher fear index for Trump

The Implications of Fear

How should we interpret the pattern of American fears and the fact that fears seem to be rising across the board over recent years? Again, I will not try to draw sweeping conclusions at this point. Instead, I note two important questions raised by the data presented here.

First, are we worrying the right amount about the right things? As noted above, fear can be an important motivator for self-protection. Americans should discuss the threats and risks to national security, to public health, and the future of the planet. But even a cursory glance at the pattern of topical fear indexes suggests that threat perception is not an entirely rational process. What is not helpful, in particular, is hyping threats to such a degree that society over invests in policies to deal with them, while underinvesting in dealing with other threats. An important agenda, therefore, is the attempt to determine how closely the nation’s fear discourse mirrors the real world and what sorts of factors tend to distort it.

Second, what exactly is the AFI telling us? If the increase in fear related discourse is simply a response to an increasingly dangerous world, then the AFI is a measure of a healthy marketplace of ideas. If, on the other hand, the AFI reflects competition among elites to use fear for political purposes, then the AFI represents not a healthy marketplace of ideas but instead one held captive to propaganda. Or, perhaps even worse, rising fears may reflect the loss of public confidence in the ability of the democratic process to meet the challenges of the day. If this is the case, then the AFI may be a measure of our society’s weakening cohesiveness and resilience.