Forty years ago, in the spring of 1978, I had no intention of becoming an economist. Instead, I was studying marine biology at Duke University’s Marine Lab at Pivers Island, on the beautiful North Carolina Coast. There, when the wind was up, my classmate Alan Kahana and I enjoyed going out on his Hobie 16, with Alan manning the tiller and myself hiked-out on the trapeze. We weren’t, truth be told, especially prudent sailors. On the contrary: we were so inclined to push things to the limit that one day we took the Hobie out just as a gale was getting up, and ended up…well, that’s a long, sad story. Suffice to say that it doesn’t take much to capsize a Hobie, and that on that day we capsized Alan’s boat once and for all.

What, you are no doubt wondering, has any of this to do with Interest on Excess Reserves? I’m getting there. You see, although it doesn’t take much to capsize a Hobie — a little over-trimming of the sail will suffice — once one capsizes, it’s likely to start to turn turtle as its mast fills with water. And as that’s happening, it may be all that two reasonably trim lads can do — by pulling for dear life on a righting line attached to the boat’s mast, whilst leaning backwards on its uppermost hull — to lever the thing back upright. The more the mast fills, the harder it gets. And the same sort of thing goes for letting a central bank slip into, and then trying to wrest it out of, a floor system of monetary control: the more liquidity the banking system takes in while that system’s in place, the more effort it takes to pull out of it.

As faithful readers know, I’ve long insisted that the modest interest rates the Fed began paying on excess reserves in October 2008 were enough to encourage bankers, who long made do with only the slimmest of excess reserve cushions, to hoard all the reserves they could lay their hands on. That modest little bit of Fed sail-trimming was enough to overturn the Fed’s traditional monetary control system. The Fed had long relied on a sort of asymmetrical “corridor” system, with a target fed funds rate set somewhere between zero and the Fed’s discount rate, and the effective federal funds rate kept near that target by means of small-scale open market operations. Now it had flipped-over to a “floor” system, with changes in the Fed-administered IOER rate serving as its chief instrument of monetary control.

Some economists, to be sure, refuse to believe that the modest IOER rates the Fed paid in the early stages of the crisis could account for the switch in question, or for banks’ subsequent tendency to hoard reserves. Paul Krugman even accused those who thought so of failing a “reality test,” by overlooking how, in the U.S. in the 1930s and in Japan more recently, banks hoarded non-interest-bearing reserves. But Professor Krugman himself might be said to have failed a “logic test,” calling for an understanding of the difference between a necessary and a sufficient cause. Then there’s the pesky fact that Ben Bernanke and other Fed officials secured permission to pay interest on bank reserves for the express purpose of getting banks to hoard them. Had they done so for no reason? Had Ben Bernanke himself forgotten about the 1930s? A page from his 2014 textbook is illuminating (HT: Alex Schibuola):

But allowing that a modest above-zero return on bank reserves was indeed all it took to establish a floor system, and to get banks to stock-up on excess reserves, it doesn’t follow that restoring the IOER rate to zero would have the opposite effects. The reason has to do with the immense growth in the total supply of reserve balances that has since taken place. That growth matters because, under a floor system, the greater the nominal stock of bank reserves, the lower the IOER rate must be to reduce the quantity of excess reserves demanded to zero. The accumulation of liquidity in a “floored” monetary control system thus acts like the accumulation of water in the mast of a capsized Hobie Cat, making it much harder to revert from a floor to a corridor system than it was to switch to the floor system in the first place. Call it the Hobie Cat effect.

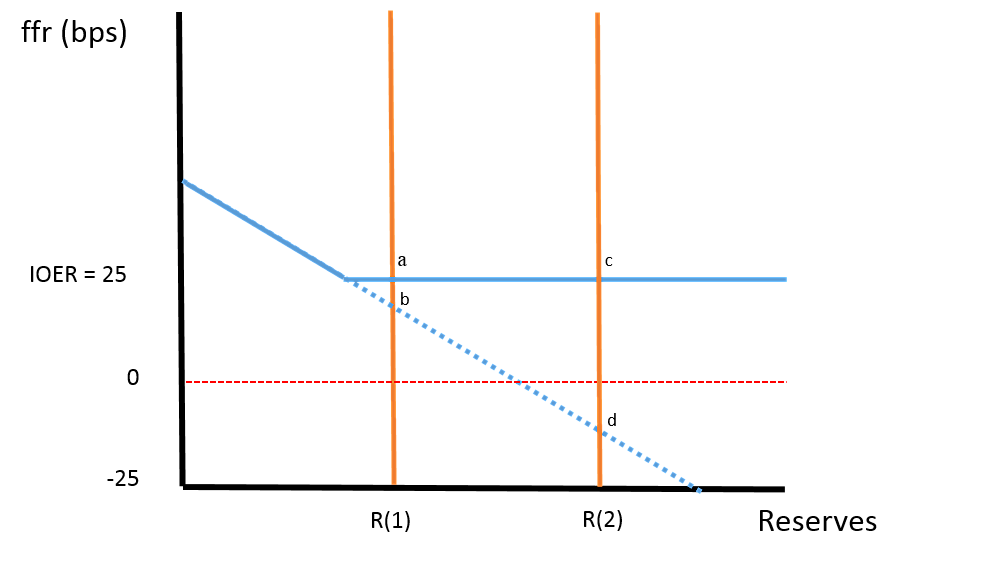

The Hobie Cat effect can be illustrated formally using a diagram showing the supply of and demand for bank reserves or federal funds under a floor system. The supply schedule for federal funds is, as usual, a vertical line, the position of which varies with changes in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. The reserve demand schedule, on the other hand, slopes downward, but only until it reaches the going IOER rate, here initially assumed to be set at 25 basis points. At that point the demand schedule becomes horizontal, because banks would rather accumulate excess reserves that yield the IOER rate than lend reserves overnight for an even lower return.

For the initial stock of reserves R(1), starting at the equilibrium point “a,” a slight reduction in the IOER rate would suffice to get the banking system back onto the sloped part of its reserve demand schedule, at point “b,” where reserves are again scarce at the margin. But once the stock of reserves has increased to R(2), it takes a much more substantial reduction in the IOER rate — perhaps, as the move in the illustration from “c” to “d” suggests, even into negative territory — to make reserves scarce at the margin again, and to thereby make switching to a corridor system, by a modest further reduction in the IOER rate, possible without any need for central bank asset sales.[1]

Does this mean that the Fed can never hope to escape from its current floor system unless it reduces its IOER rate substantially, and that it might even have to resort to a negative rate? It doesn’t. And it’s here that the Hobie Cat analogy fails, for while you can’t drain the mast of a Hobie Cat that’s turned turtle, the Fed can drain the banking system of any or all of the reserves it created after 2008. The obvious, and most prudent, way out of the floor system is, therefore, for the Fed to retrace the steps that got it into that system, by first shrinking its balance sheet far enough to return the stock of reserves to a point close to the kink in the federal funds demand schedule, and then reducing the IOER rate enough to make reserves scarce at the margin, thereby reviving interbank lending and establishing a corridor system.

Considering how many excess reserves banks are now holding, all of this is still a tall order. But it beats having an operating framework that leaves our monetary system sodden and adrift.

____________________________

[1] Because the move from “c” to “d,” like that from “a” to “b,” involves no change in the total stock of bank reserves, readers may be tempted to assume that it also involves no reduction in the quantity of excess reserves, and hence no change in banks’ inclination to hoard such reserves. The temptation should be resisted: although banks hold the same total quantity of reserves at “d” as at “c,” the former equilibrium involves a higher quantity of bank lending and deposit creation, hence a higher value of required reserves, with a correspondingly lower value of excess reserves.