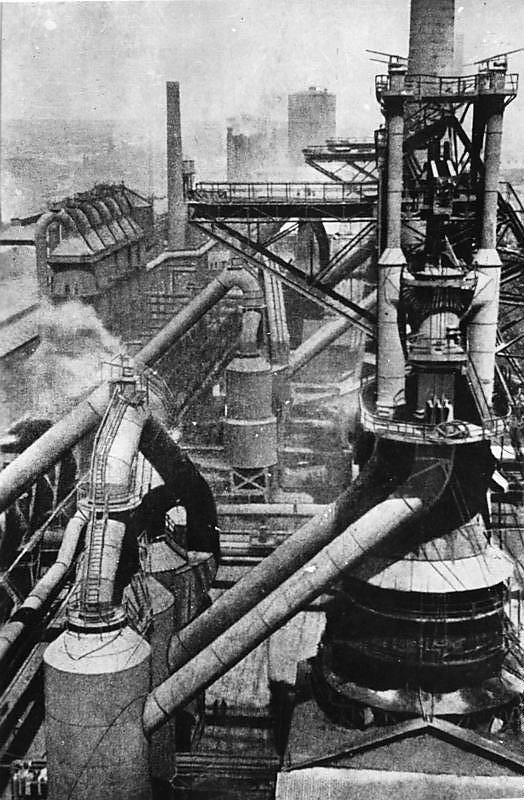

Though a monument to the ravages of Soviet central planning, the barren Magnitogorsk steel works complex still inspires America’s industrial policy proponents. “Failure to plan is a plan for failure,” said comrade Rep. Dan Lipinski (D‑IL), as he described the “pro-manufacturing” legislation he helped slip into the mammoth Cromnibus bill, which became law this month.

The Revitalize American Manufacturing and Innovation Act directs the Secretary of Commerce to establish a “Network for Manufacturing Innovation” to:

- improve the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing and increase production of goods manufactured predominately within the United States;

- stimulate U.S. leadership in advanced manufacturing research, innovation, and technology;

- accelerate the development of an advanced manufacturing workforce; and

- create and preserve jobs

Of course, the verbs “revitalize,” “improve,” “stimulate,” “accelerate,” “create,” and “preserve” are euphemisms for protect, subsidize, regulate, and intervene.

From Lipinsky’s perspective:

This is a big victory for a sector of our economy that over the years has provided so many high quality jobs in my district, in our region, and across the nation, but has taken many hits over the past couple of decades, especially during the recent recession. While manufacturing is by-and-large a private, market endeavor, few can disagree that government policy impacts manufacturing in countless ways.

Yes, government policy has affected manufacturing in countless–usually adverse–ways. Excessive regulations enabled by irresponsible agency cost-benefit analyses, a burdensome tax system, endemic exposure to frivolous lawsuits, exorbitant health care costs, inefficient union work rules, tariffs on industrial inputs, absurd restrictions on immigration, subsidization of chosen firms, and other forms of corporate favoritism are all drags on manufacturing (and other economic sectors, too). U.S. manufacturing would benefit from less Washington, not more.

The Revitalize Act is a solution in search of a problem – and a bad solution at that. American manufacturing does not need revitalizing. Despite Washington’s many meddling interventions, and despite the persistence of the myth of U.S. industrial decline, U.S. manufacturing is thriving–and always has been. Year after year, with the exceptions of during cyclical recession, new records are set with respect to most relevant industry health metrics. The most recent official data reveal all-time highs for manufacturing sector output, value-added, revenues, exports, profits, and foreign direct investment–all in real terms and all achieved, largely, in the absence of top-down planning.

Moreover, for a country whose consumers spend twice as much on services than on goods, and where 90 percent of the workforce is employed outside the manufacturing sector, official obsession over the future of manufacturing is more than a bit overplayed. Many with this obsession dwell on the past, evoking the good old days of 1979, when the sector employed almost 20 million workers, or 1953, when manufacturing accounted for a record 28 percent of U.S. GDP. But today’s manufacturing worker produces an average of $170,000 of value-added per year, as compared to $28,000 in 1979–a more than quadrupling of output in real terms. And, although manufacturing’s share of the economy has declined to about 12 percent today, the absolute value of U.S. manufacturing output, in real terms, has increased more than six-fold since 1953. The facts that the sector supports far fewer jobs today and accounts for a smaller share of the U.S. economy say absolutely nothing about the state of the manufacturing.

What matters is whether there is continued growth in value-added, revenues, foreign direct investment, research and development expenditures, capital expenditures, and productivity. By each of those measures, U.S. manufacturing is robust. When it comes to the question of the condition of U.S. manufacturing, which is likely to be a more credible barometer: legislators who benefit from the perception of fixing “manufactured” problems or investors revealing their preferences through their own actions? As of 2013, nearly $1 trillion of foreign direct investment was parked in U.S. manufacturing, by far the number-one manufacturing investment destination in the world. That’s a rather strong endorsement of the state of U.S. manufacturing.

How on earth would U.S. manufacturers–the world’s most advantaged with their unparalleled access to idea incubators, research universities, R&D laboratories, and broad and deep capital markets to commercialize the ideas that make it through a rigorous vetting process–benefit from the Commerce Department’s participation in mapping out the future? Sure, some firms in some manufacturing industries–those that succeed in convincing the government that they are worthy of public support (i.e., those that commit more resources to political, rather than economic, activities)–may benefit. But others, which rely upon and adapt to the verdicts of consumers in a market environment, will be disadvantaged.

Industrial policy is anathema to the market. It short-circuits a selective, evolutionary process that has undergirded the world’s most successful innovation machine and reduces chances of worthy ideas, firms, and industries leading the next commercial wave. Did the last generation’s policymakers anticipate the arrival of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, or Mark Zuckerberg and the revolutionary products and services they delivered? Did Washington bureaucrats foresee the advent of specific life-extending medicines and devices, like swallowable, pill-sized cameras? Had those proposing industrial policy in response to a rising Japan in the 1980s and early 1990s prevailed, much of the technology and medical advances taken for granted today would have never come to fruition. American manufacturing and the broader U.S. economy have been successful by shunning, more than embracing, industrial policy.

With its pre-eminence in innovation and entrepreneurship still intact, the United States is situated at the top of the global value chain. Staying there will require Americans to remain skeptical of top-down industrial policy. It could propel the United States above Kazakhstan as the world’s greatest producer of potassium, but at unthinkable costs.