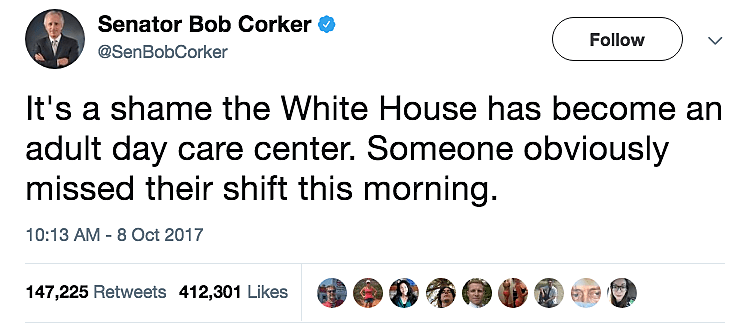

In Sunday’s episode of “Reality-Show Presidency,” we found out what happens when the president and the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee “stop being polite… and start getting real.” After President Trump blasted him in a series of tweets early Sunday, Sen. Bob Corker (R‑TN) shot back:

Senator Corker is hardly the only highly placed Republican to express grave doubts about Trump’s stability and competence. Daniel Drezner has assembled a list—now at 115 items and counting—of news stories in which the president’s own aides or political allies talk about him as if he’s a “toddler.” But since Corker’s not running for reelection, he felt free to go on the record: Trump “concerns me,” Corker said in an interview later that day, “he would have to concern anyone who cares about our nation.” His recklessness and lack of emotional discipline could, Corker said, put us “on the path to World War III.”

In Corker’s account, it’s an open secret that our 45th president is a walking constitutional crisis. Is there a constitutional remedy?

The conventional wisdom says no: we have impeachment if the president turns out to be a crook, and the 25th Amendment if he falls into a coma—but for anything in between “felon” and “vegetable,” tough luck. When he introduced his article of impeachment against President Trump this summer, Rep. Brad Sherman (D‑CA) explained that he’d focused on obstruction of justice because, sadly, “the Constitution does not provide for the removal of a President for impulsive, ignorant incompetence.”

But when it comes to “the most powerful office in the world,” impulsive, ignorant incompetence can be as damaging as willful criminality. Did the Framers really leave us defenseless against it?

Actually, no: impeachment’s structure, purpose, and history suggest a remedy broad enough to protect the body politic from federal officers whose lack of stability and competence might cause serious harm. Contrary to the conventional wisdom, there’s no constitutional barrier to impeaching a president whose public conduct makes reasonable people worry about his access to nuclear weapons.

We tend to think of presidential impeachments in terms of the paradigmatic case: a corrupt, criminal president who abuses his power. Richard Nixon quit before he was actually impeached, but his case rightfully looms large in the public understanding of what the mechanism is for. As Cass Sunstein writes in his forthcoming book Impeachment: A Citizen’s Guide, “If a president uses the apparatus of government in an unlawful way, to compromise democratic processes and invade constitutional rights, we come to the heart of what the impeachment provision is all about.”

But that’s not all impeachment is about. During the Philadelphia Convention’s most extensive period of debate on the remedy’s purpose, James Madison declared it “indispensable that some provision should be made for defending the community against the incapacity, negligence, or perfidy of the Chief Magistrate.” Those faults might be survivable when they afflict individual legislators, Madison argued, because “the soundness of the remaining members would maintain the integrity and fidelity” of the branch as a whole. But “the Executive magistracy… was to be administered by a single man,” and “loss of capacity” there “might be fatal to the Republic.”

In practice, impeachment has never been limited to cases of “perfidy” alone. In its comprehensive report on the “Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment,” the Nixon-era House Judiciary Committee staff identified three categories of misconduct held to be impeachable offenses in American constitutional history: abuse of power, using one’s post for “personal gain,” and, most important here, “behaving in a manner grossly incompatible with the proper function and purpose of the office.” The House has the power to impeach, and the Senate to remove, a federal officer whose conduct “seriously undermine[s] public confidence in his ability to perform his official functions.”

One of our earliest impeachments—the first to result in a federal officer’s removal—fell into that category. It involved federal judge John Pickering, a man “of loose morals and intemperate habits,” per the charges against him. Pickering had committed no crime, but was removed by the Senate in 1804 for the “high misdemeanor” of showing up to work drunk and ranting like a maniac in court. Such conduct was “disgraceful to his own character as a judge, and degrading to the honor and dignity of the United States.”

Nor was Pickering the only federal official to lose his post for erratic behavior demonstrating unfitness for high office. Others include judges Mark Delahay (1873), “intoxicated off the bench as well as on the bench,” and George W. English (1926), whose bizarre conduct included, among other things, summoning “several state and local officials to appear before him in an imaginary case,” and haranguing them “in a loud, angry voice, using improper, profane, and indecent language.” “By his decisions and orders he inspired fear and distrust” Article V summed up, “to the scandal and disrepute of said court.”

Do precedents from judicial impeachments count when it comes to the presidency, an office with vastly greater powers and responsibilities? No doubt the attempted removal of an elected president is more serious and potentially disruptive than impeachment of one of hundreds of federal judges. But the argument that presidents are singularly important cuts both ways: it’s far more dangerous to leave an unfit president in office than an unfit judge. Judges don’t have the federal law enforcement apparatus or the massive destructive capacity of the US military at their disposal.

In any event, there’s presidential precedent available as well, from the 1868 impeachment of Andrew Johnson, whom Princeton political scientist Keith Whittington has called “the pre-modern Trump.” The 10th article of impeachment against Johnson charged the president with “a high misdemeanor in office” based on a series of “intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues” he’d delivered in an 1866 speaking tour. Those speeches, according to Article X, were “peculiarly indecent and becoming in the Chief Magistrate” and brought his office “into contempt, ridicule, and disgrace.”

Johnson, who’d been blotto for his maiden speech as vice president, was supposedly sober during the “Swing Around the Circle” tour, during which he accused Congress of, among other things, “undertak[ing] to poison the minds of the American people” and having “substantially planned” a race riot in New Orleans that July.

Much of the offending rhetoric cited in Article X wouldn’t be considered particularly shocking today, but at the time, it was a radical departure from prevailing norms of presidential conduct. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, dragged along on the tour, wrote to his wife that “I have never been so tired of anything before as I have been with the political stump speeches of Mr. Johnson. I look upon them as a national disgrace.”

Article X never came to a vote in the Senate, having been abandoned after failure to convict on what were believed to be the strongest charges against Johnson. Nor was it uncontroversial at the time.

But according to Rep. Benjamin Butler (R‑MA), a key impeachment manager in the Johnson case, the backlash against the president’s speeches made impeachment possible: “they disgusted everybody.” As Jeffrey Tulis explained in his seminal work The Rhetorical Presidency, “Johnson’s popular rhetoric violated virtually all of the nineteenth-century norms” surrounding presidential popular communication: “he stands as the stark exception to general practice in that century, so demagogic in his appeals to the people” that he resembled “a parody of popular leadership.”

Johnson’s behavior was, you might say, “not normal,” and what is “not normal” can sometimes be impeachable. On a number of occasions, the House has deployed that “indispensable” remedy against federal officers who, by their acts, revealed defects of intellect, character, and temperament “grossly incompatible with the proper function and purpose of the office.” Deliberate, criminal abuse of power may be “the heart of impeachment,” but our constitutional history suggests that the remedy is broad enough to reach “impulsive, ignorant incompetence” in an extreme case—should one happen to crop up.

Through all the chatter about Emoluments and Russian plots, “not normal” is at the heart of the fears evoked by the Trump presidency. That recurring lament, heard even from Republican Senators, often involves the president’s Twitter feed, his outlet for tantrums about bad restaurant reviews, Saturday Night Live skits, “so-called judges” who should be blamed for future terrorist attacks, and the United States’ nuclear-armed rivals.

In public appearances, Trump is equally incontinent. Whether he’s addressing CIA officers in front of the “Memorial Wall” at Langley or a gaggle of Webelos at the National Boy Scout Jamboree in West Virginia, the president rants about “fake news,” blasts his political enemies, and brags about the size of his Inaugural crowd. It’s a strange feeling when you find yourself almost relieved he didn’t take the opportunity to tell 30,000 Boy Scouts: “check out sex tape.”

Fans of the president’s speechifying praise him for “shaking things up” and “telling it like it is”—as if it’s only hypocritical Beltway pieties he’s skewering. Just as often, Trump tramples the sort of tacit norms that separate us from banana republic status, like: a president shouldn’t tell active-duty military to “call those senators” on behalf of his agenda, suggest that his political opponents should be put in jail, or make off-the-cuff threats of nuclear annihilation.

Still, in the current debate over impeachment, the conventional wisdom reigns. Even those who desperately want to repeal and replace the Trump presidency are convinced removal would be constitutionally illegitimate unless it can be shown that the president is a crook or a certifiable loon.

As a result, they’re engaged in an awkward effort to shoehorn Trump’s ignominies into either a criminal or a clinical model. Impeachment advocates, like Rep. Sherman, emphasize obstruction of justice and tales of Kremlin conspiracies. Supporters of the “25th Amendment Solution,” like Ross Douthat and Rep. Jamie Raskin (D‑MD) strain to categorize Trump’s verbal incontinence as some sort of mental disorder.

My guess is, if you put Sherman, Douthat, Raskin et al on the couch for a word-association test (“say the first thing that comes to your mind…”), “Trump” might elicit responses like “crooked” or “insane,” but you’d probably get a lot more along the lines of “reckless,” “juvenile,” “incompetent,” “clownish”—and perhaps a few unprintable epithets.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson used an epithet of his own, if you believe the recent reports. The original NBC News story had Tillerson referring to his boss as a “moron” at a Pentagon meeting this summer; one of the reporters, later said that according to her source, it was actually “[expletive deleted] moron.”

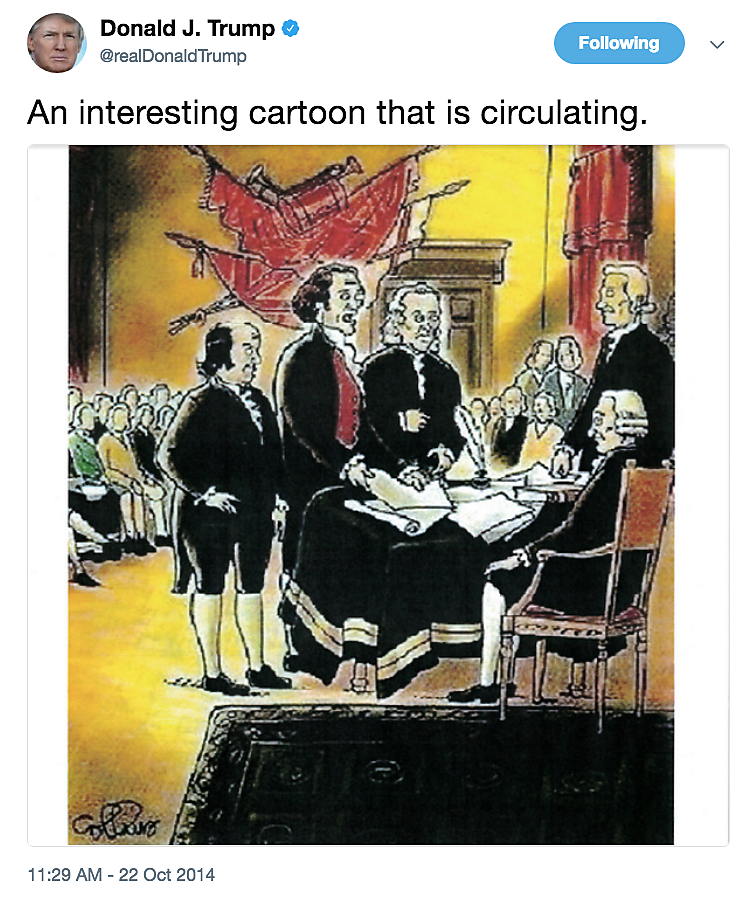

Like they say, there really is “a tweet for everything.” After the Tillerson story broke, internet sleuths went hunting, and someone dug up this gem from Trump’s feed, when he was subtweeting then-president Obama in October 2014.

The Framers are gathered at the Philadelphia Convention and one says: “I keep thinking we should include something in the Constitution in case the people elect a [expletive deleted] moron.”

Zing! But—just maybe—they did include something.