If the Democrats take the House, they’ll impeach Justice Kavanaugh, President Trump warned at a mass rally in Iowa last week. “Impeach, for what? For what?” Trump demanded. For perjury, most likely: “If we find lies about assault against women,” says Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D.-Ill.) one of several House Judiciary Committee members calling for renewed investigation, “then we should proceed to impeach.”

I’m not the newly-minted Justice’s biggest fan. From the start, I thought Kavanaugh was a lousy pick for the Court: weak on the Fourth Amendment and unreasonably fond of extraconstitutional privileges for the president. I’ve also argued, at great length, that we ought to impeach federal officers more frequently than we do. That goes for Supreme Court Justices as well. The Framers thought impeachment could serve as a valuable check on abuses of judicial power: that we’ve managed to impeach just one member of the “high court” in 230 years is pretty anemic.

All that said, I find the case for impeaching Justice Kavanaugh uncompelling, for the reasons that follow.

It’s true that there’s ample precedent for impeaching federal judges for perjury. Our last five judicial impeachments were based on charges of lying under oath.

Here’s a brief rundown of each case: in 1986, the House impeached, and the Senate removed, Judge Harry E. Claiborne (D. Nev.) for filing false tax returns under penalty of perjury (Claiborne had been convicted of those offenses earlier that year, becoming the first sitting federal judge to be incarcerated). Three years later, the Senate removed two more judges for lying under oath. One, the inauspiciously surnamed Walter L. Nixon (S.D. Miss.), was serving five years in prison for lying to a federal grand jury about his attempt to influence a drug smuggling prosecution. The other, Alcee L. Hastings (S.D. Fla.), had been prosecuted for soliciting a $150,000 bribe in exchange for reducing the sentences of two mob-connected developers who’d robbed a union pension fund. He beat the rap in court, but lost his post when the Senate voted to remove him for the bribery scheme and perjuring himself at trial. (Hastings bounced back pretty quickly, however, winning election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1992. He currently represents Florida’s 20th congressional district.)

More recently, we have the grotesque behavior of Judge Samuel Kent (S.D. Tex.), impeached in 2009 for sexually assaulting two court employees and lying about it to federal investigators. (Kent resigned before completion of his Senate trial.) Finally, there’s Judge G. Thomas Porteous (E.D. La.), impeached and removed in 2010 for “a longstanding pattern of corrupt conduct,” including kickbacks from attorneys, perjury in his personal bankruptcy filing, and “knowingly ma[king] material false statements about his past” to the Senate Judiciary Committee “in order to obtain the office of United States District Court Judge.”

In principle and in practice, then, perjury is an impeachable offense. That obviously includes lying under oath to gain confirmation to higher office. In Monday’s Wall Street Journal, David Rivkin and Lee Casey insist that “Justice Kavanaugh cannot be impeached for conduct before his promotion to the Supreme Court,” including “any claims that he misled the Judiciary Committee.” But that’s nonsense. Misleading the Judiciary Committee about prior conduct was precisely what was at issue in the Porteous impeachment.

And yet, the cases outlined above differ from Brett Kavanaugh’s in at least one crucial respect: in each of them, Congress had overwhelming evidence of impeachable falsehoods. Claiborne, Nixon, and Kent were already in federal prison when the House voted to impeach. Hastings and Porteous were removed after exhaustive investigations pursuant to the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act convinced their colleagues impeachment referrals were warranted. Indeed, despite Hastings acquittal in his criminal trial, a Judicial Investigating Committee concluded there was “clear and convincing evidence” he lied and falsified documents in order to mislead the jury.

When it comes to the central charge against Kavanaugh, however, clear and convincing evidence is unlikely to emerge. I don’t know if he’s lying about whether he sexually assaulted Christine Blasey Ford in the early ‘80s, and neither do you. It’s hard to imagine that further investigation, however exhaustive, will lead to dispositive proof one way or the other.

Members of Congress are, of course, free to adopt a less stringent burden of proof—and maybe they should. The Constitution’s impeachment provisions nowhere specify clear and convincing evidence, proof beyond a reasonable doubt, or any particular evidentiary standard. That recent judicial impeachments have mirrored criminal-law standards is a result of the post-1980 statutory regime for disciplining federal judges and the “Overcriminalization of Impeachment” more generally. Since the purpose of impeachment is less to punish bad actors than to expel unfit officers, looser standards are arguably warranted.

But unless members of Congress are willing to proceed on something closer to reasonable suspicion, any attempt to impeach Justice Kavanaugh would have to focus elsewhere, where the evidence for false statements is stronger. Did he testify falsely “regarding what he knew about emails stolen from the Senate Dems by a Republican operative” in judicial confirmation fights in the early 2000s? Did he attempt to mislead the Senate about his high-school yearbook?

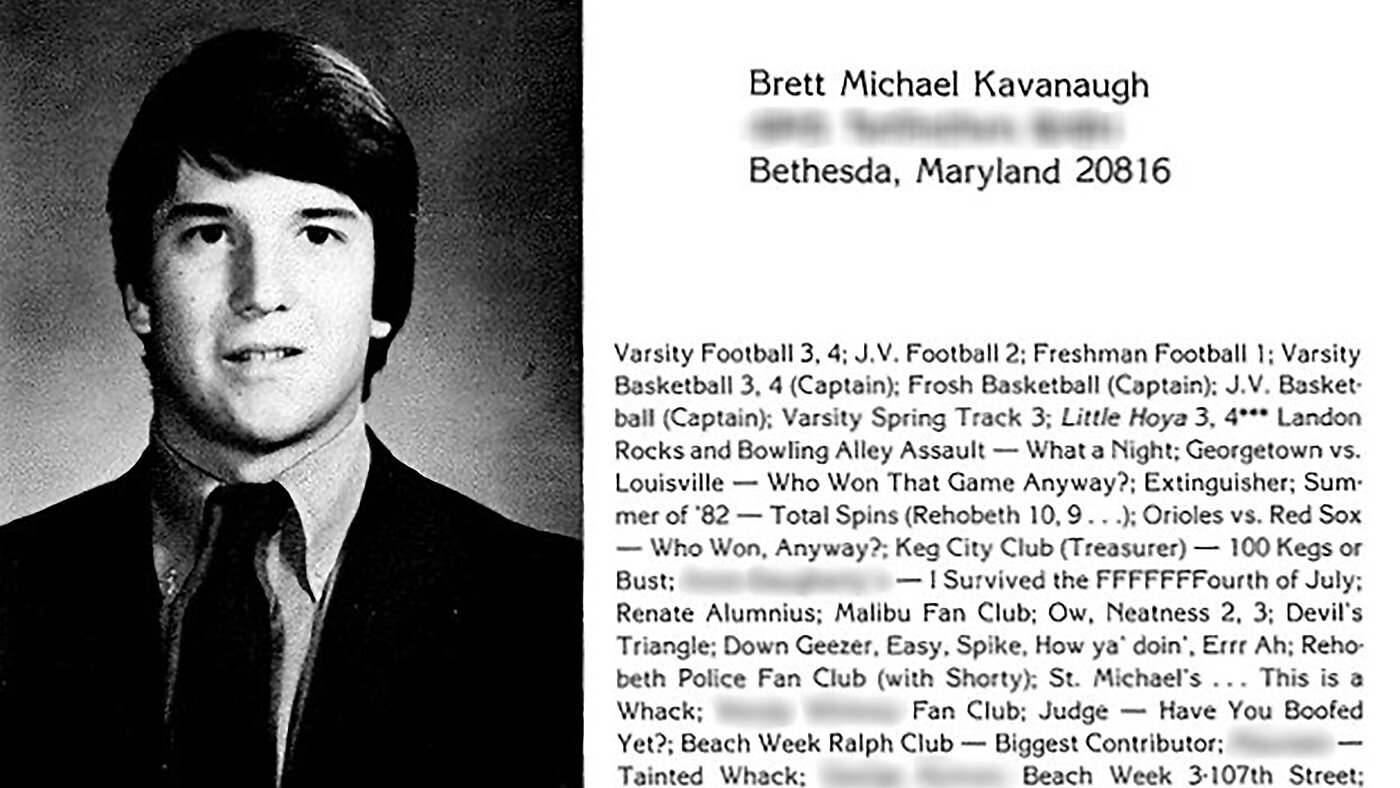

In fact, I strongly suspect Kavanaugh lied about several items on his yearbook page. Was the reference to “Renate Alumnius” really just “intended to show affection” toward a female student at a nearby school? Was “boof[ing]” meant to indicate “flatulence”? I went to high school in the mid-Atlantic in the ‘80s, several years after Kavanaugh graduated, and I remember the term being a corny euphemism for sex. That usage better fits what Kavanaugh actually wrote—“Judge—Have You Boofed Yet?”—unless we credit him with unusual concern about his drinking buddy’s intestinal discomfort.

But just going through the “boof-sleuthing” exercise in the prior paragraph cost me several IQ points and a soupçon of self-respect. The Framers viewed impeachment as a solemn and serious affair. Hamilton described “the awful discretion which a court of impeachments must necessarily have, to doom to honor or to infamy the most confidential and the most distinguished characters of the community.” A Kavanaugh impeachment inquiry would be awful in a different way: a spectacle proving mainly that high school never ends.

“Imagine what it would look like,” writes Stephanie Mencimer in Mother Jones:

Hours of testimony from Squi, Timmy, and PJ over whether a Devil’s Triangle is really, as Kavanaugh testified, a drinking game. Expert debates over the definition of “boofing.”…. Michael Avenatti could figure prominently. It’s the kind of stuff that could end up making former House Oversight Committee chairman and Benghazi conspiracy theorist Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R‑Utah) look like an elder statesman.

Really, must we? Sure, it might be entertaining to hear Rep. Alcee Hastings (D‑Fla.), impeached for lying about participation in a gangland bribery scheme—and lately dogged by his own sex scandal—justify a vote to impeach over “Renate Alumnius.” But the proceeding as a whole would hardly be edifying.

A much-discussed recent survey puts two-thirds of Americans into a category the authors dub “the exhausted majority”—voters who are “frustrated and fed up with tribalism.” A Kavanaugh impeachment effort seems tailor-made to exhaust them even further.