Germany introduced a new economy-wide minimum wage for the first time in 2015, at a relatively high rate of €8.50 ($9.67 today). This rose to €8.84 in 2017. For reference: between 10 and 14 percent of eligible workers were thought to earn less than €8.50 before the policy was introduced.

This is interesting from a research perspective. Most minimum wage studies examine the impact of minimum wages at low levels or assess small changes to their rate. But here we have a case study of a whole regime change with a high rate introduced for the first time.

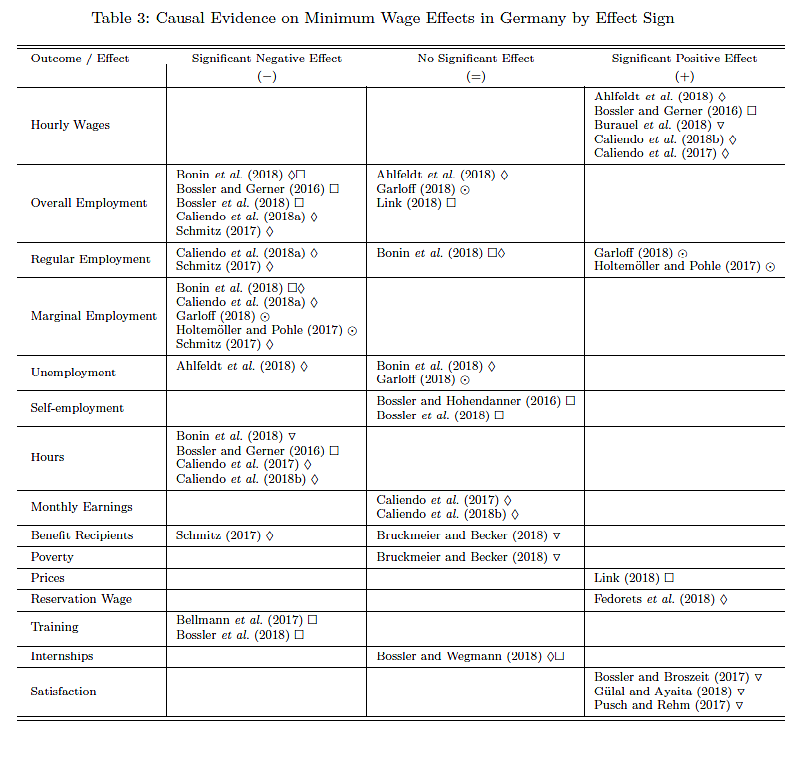

A new paper by IZA Institute of Labor Economics provides a clear literature review on the effects so far. Studies have exploited three different strategies to assess the impact: utilizing regional variation of the “bite” of the minimum wage, using treatment and control groups, and assessing the impact on firms. As the table below shows, a broad consensus is emerging, which sits well within the existing minimum wage literature:

- Unsurprisingly, hourly wages have increased at the bottom of the income distribution, though there is little evidence of a ripple effect further up.

- Most studies find a small but negative effect on overall employment (up to 260,000 fewer jobs), driven by reduced hiring (not layoffs) and a reduction of casual and atypical employment.

- All studies that assessed it find a negative effect on contractual hours.

- As a result, although hourly wages increased, the reduction in hours meant gross monthly earnings does not appear to have increased much for low-paid employees.

- Since gross monthly earnings have not substantially increased, and those earning minimum wage are often not from the poorest households, the policy hasn’t seemingly reduced the risk of being in poverty.

For more on the state of the academic debate on minimum wages, read my Regulation article.