Hudson Institute historian and political scientist John Fonte has written that immigrants are not patriotically assimilating. Fonte blames this supposed development on many factors but frequently credits changes in public school curricula away from the nation building Americanization Movement of the Progressive Era toward a multicultural ethos today. In previous posts, I have challenged Fonte’s claims about a lack of patriotic assimilation amongst today’s immigrants and have shown that his claims about the success of the Americanization Movement are based on anecdotes and that there as many that show it actually slowed assimilation.

A more subtle reading of Fonte’s work is that he is worried about immigrants and their descendants weakening American political institutions by not supporting them as much as Americans whose ancestors have been here for many generations. The General Social Survey (GSS) asks many questions of immigrants and their descendants that can help lessen Fonte’s worries.

The following are responses to the question from the pooled years 2004–2014:

I am going to name some institutions in this country. As far as the people running these institutions are concerned, would you say you have a great deal of confidence, only some confidence, or hardly any confidence at all in them? [Insert Institution]

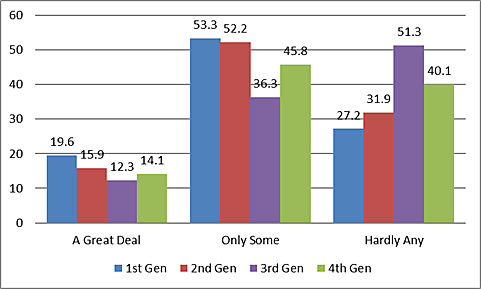

Figure 1 shows confidence in the executive branch of government by generation. Immigrants are more likely than any other generation to have “a great deal” or “only some” confidence in the Presidency and they are the least likely to have “hardly any.” The third generation appears to have the least confidence. Over the generations, confidence diminishes and then rebounds slightly for Americans whose grandparents were all born here (fourth generation and greater Americans). Immigrant confidence in the executive branch could weaken during the Presidency of Donald Trump due to his positions on immigration, relative to those of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, but we will have to wait until additional GSS surveys are released in the coming years.

Figure 1

Confidence in Executive Branch of Government

Source: General Social Survey.

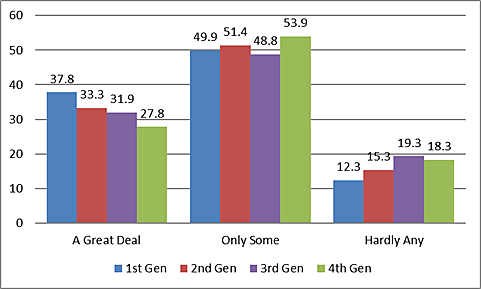

Immigrant confidence in the Supreme Court is also relatively high (Figure 2). Almost 38 percent of them have “a great deal” of confidence, more than any other generation, and 49.9 percent have “only some” confidence. Immigrants are the least likely to say they have “hardly any” confidence in the Supreme Court. Again, third-generation Americans are the most likely to have “hardly any” confidence in the institution.

Figure 2 Confidence in Supreme Court

Source: General Social Survey.

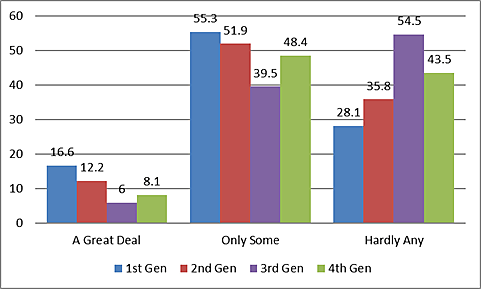

Congress is extremely unpopular and this is reflected in the confidence results for every group (Figure 3). Immigrants are the most likely to have “a great deal” of confidence and “only some” in Congress. They are also the least likely to have “hardly any” confidence in Congress. Once again, third-generation Americans are the most likely to have “hardly any” confidence in Congress with 54.5 percent agreeing with that sentiment. Confidence in Congress rebounds slightly in the fourth generation.

Figure 3

Confidence in Congress

Source: General Social Survey.

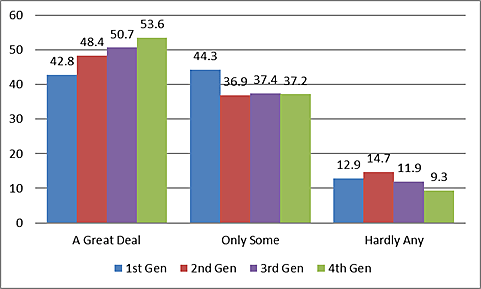

Confidence in the U.S. military shows a slightly different trend (Figure 4). Immigrants have a relatively large amount of confidence in the Executive, the Supreme Court, and Congress that then diminishes in subsequent generations. Immigrants have the lowest degree of “a great deal” of confidence in the military, the highest degree of “only some” confidence, and the second most likely to have “hardly any.” Later generations tend to have more confidence but the differences are small if you look at responses for “hardly any.”

Figure 4

Confidence in U.S. Military

Source: General Social Survey.

Immigrant confidence in the Presidency, Congress, and the Supreme Court is actually higher than it is for subsequent generations while confidence in the military is a bit lower initially but climbs in every successive generation. Rather than having lower confidence in the institutions of American government, immigrants tend to have more confidence which is not what you would expect from reading Fonte’s research. A component of assimilation seems to be diminished confidence in American governmental institutions over the generations. Fonte does write that immigrant civic knowledge lags behind that of native-born Americans – perhaps knowledge or familiarity with our government’s institutions breeds dislike?

Another potential explanation for high immigrant confidence in American government institutions is that immigrants generally come from countries with worse political institutions than the United States. Their experiences with and observation of American political institutions leads to more positive opinions based on their relative experience in their home countries. Americans whose ancestors have been here longer do not know how good they have it relative to today’s immigrants who have personal experience with worse governments. As a personal anecdote, as a young adult, I remember complaining about the U.S. government and being told by my immigrant relatives that it is so much better here than in Iran. I have not forgotten that and it has made me more optimistic than most despite all of the obvious problems with our government’s institutions.