Some officials at Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) are reportedly looking into the agency joining the Intelligence Community (IC). Making ICE, which is responsible to deportations, a member of the IC would be a mistake, putting our civil liberties at risk by giving the agency increased access to vast troves of information not related to immigration enforcement.

ICE officials have been pushing for this change since the Obama administration, but the close relationship between intelligence agencies and immigration enforcement officials is nothing new. Almost one hundred years ago, one of the most notorious set of deportations in American history occurred, thanks in large part to domestic law enforcement acting like a spy agency.

In 1919 followers of the Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani sent mail bombs to dozens of prominent public figures, including Attorney General Mitchell Palmer. Although the wannabe assassins failed to kill any of their intended targets, the bombings sparked the United States’ first “Red Scare.”

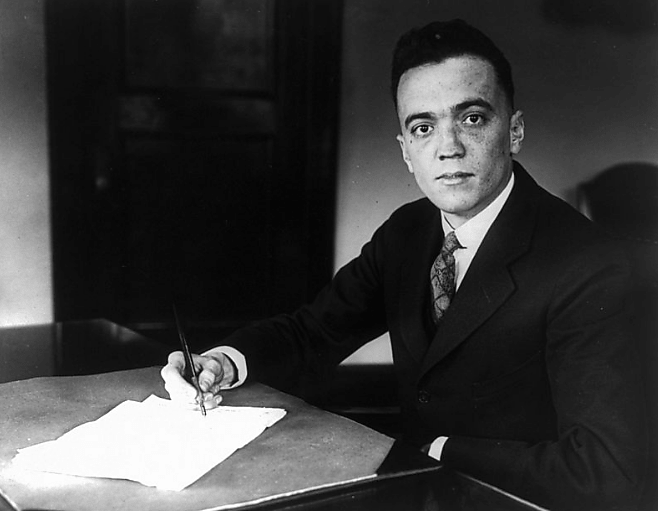

Palmer, Assistant Attorney General Francis Garvan, and Bureau of Investigation (BI) director William Flynn met shortly after bombings to decide on a course of action. They concluded that mass deportations were the solution to the Red menace, and made plans for an “Anti-Radical Division.” Garvan knew just the man to run this new agency, a 24-year-old former librarian named J. Edgar Hoover.

Hoover put his librarian skills to use, creating a database that included thousands of notecards that catalogued details related to individuals, publications, and organizations. This intelligence apparatus helped agents carry out the Palmer Raids. These raids resulted in thousands of people being arrested (many without warrants) and hundreds of “radicals” being deported.

BI agents went undercover, and local police set up “Red squads”:

Local police were encouraged to set up their own “Red squads” and share their findings with Washington. Private detective agencies, employed by the struck companies, supplied huge lists of names. Under a variety of pretexts — which included purchase, seizure, and theft — whole radical libraries were obtained. Newspapers were collected “by the bale” and pamphlets “by the ton.” Forty multilingual translators searched foreign-language periodicals for names and inflammatory quotations. Stenographers were sent to public meetings to take down the content of speeches. In Washington one-third of the BI’s special agents were assigned to antiradical work; in the field, over one-half, many of them undercover.

The BI was a law enforcement agency, but it also engaged in extensive domestic intelligence activities. Today the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the BI’s descendant, is one of the 17 agencies that make up the IC.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and ICE, the two agencies responsible for border security and deportations are not members of the IC. Yet when the president or his administration mandates a “deportation force,” “extreme vetting,” and the collection of immigrants’ social media information, immigration enforcement authorities start to look incrasingly like spy agencies.

Because ICE targets are oftentimes hard to locate, strict enforcement of immigration law requires surveillance that inevitably affects Americans and immigrants alike. Plans to access billions of license plate images and automate the monitoring of visa applicants’ online behavior will hardly leave Americans unscathed.

The fact that ICE already uses surveillance tools isn’t an argument in favor of it being a member of the IC. Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), a branch of ICE, investigates a wide range of federal crimes, including human trafficking, money laundering, and art theft. And it already has access to a plethora of information housed by the FBI, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and other law enforcement agencies.

In its last days, the Obama administration expanded the National Security Agency’s powers to share signals intelligence with other members of the IC without filtering it first. This should concern the millions of innocent Americans who communicate with or employ immigrants, because details about their lives could be swept up as part of immigration investigations, as Reason’s Scott Shackford explained:

If an American citizen is suspected of a crime that ICE is investigating, officials are required to get a warrant to get access to an American’s private communications. But if they are not the subject of an investigation or their communications get collected in intelligence-gathering that’s not about fighting crime, they do not. So, weirdly, Americans have more due process protections from warrantless snooping if they’re suspected of crimes.

For the purposes of ICE surveillance, it’s very easy to imagine that an American communicating with an immigrant (here legally or not) having his or her phone calls or communications accessed without even knowing about it. So if ICE is allowed to intrude further into the realm of intelligence, that increases the number of federal officials allowed to have access to secret snooping not just of immigrants or people in foreign lands, but of Americans here at home as well.

In addition to granting more officials access to raw signals intelligence, ICE membership of the IC would almost certainly lead to ICE engaging in “parallel construction,” a practice used and encouraged by the DEA and FBI. Using parallel construction, members of the IC share intelligence with state and local law enforcement, who then use it to make arrests. These local police departments then construct their own parallel chain of events in order to conceal the fact that IC members tipped them off. This practice, which violates the right to a fair trial, should end. If ICE joins the IC, it’s likely to occur more often.

The current administration’s immigration policies require that ICE gather and analyze more information about the lives of people living in the United States. At a time when ICE is putting more American citizens’ civil liberties at risk, administration officials should resist calls to put ICE in the IC.