If you’re looking for an upside to the Trump presidency, there’s this at least: it promises to be endless fun for executive-power geeks. That “this is not normal” means there’s plenty of opportunity to consider constitutional questions that rarely come up in periods of relative normalcy.

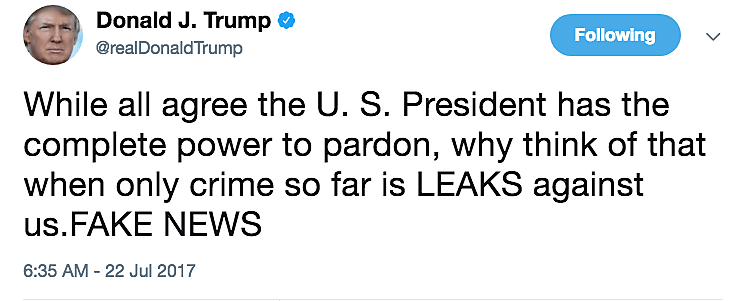

Case in point: the current debate over whether the president has the power to pardon himself, sparked by Friday’s Washington Post report that President Trump “has asked his advisers about his power to pardon aides, family members and even himself” in connection with the special prosecutor’s Russia investigation. Trump himself chimed in over Twitter Saturday:

On ABC’s “This Week” Sunday, Trump attorney Jay Sekulow denied that any such discussion had taken place, but told George Stephanopolous that “with regard to the issue of a president pardoning himself…. from a constitutional, legal perspective you can’t dismiss it one way or the other.”

It’s true that the president’s power to self-pardon isn’t clear. What is clear, however, is that if he misuses the pardon power, he can be impeached for it.

The case for a self-pardoning power rests on constitutional silence. Article II, section 2, clause 1 doesn’t specifically foreclose the possibility; it provides that the president “shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” That power, the Supreme Court has held, “is unlimited, with the exception stated.” The president can, for example, issue broad prospective pardons for federal offenses before charges have been filed. There’s little question, then, that he could at least pardon Don Jr., Jared Kushner, Paul Manafort, Mike Flynn, and anyone else who might end up in the special counsel’s crosshairs.

But could he pardon himself? The argument that he couldn’t likewise starts with the constitutional text. Brian Kalt, the author of the definitive case against presidential self-pardons, suggests that the power “is limited by the meaning of the word ‘pardon’ itself.” A pardon is inherently bilateral: it implies a donor and a recipient. “It makes no sense to talk of donating a kidney or $100 to yourself.” What’s more, “the self-pardon was nowhere mentioned in the debates [over the Constitution] or in the English history that informed them.” Why read that silence to indicate a power fundamentally at odds with the Constitution’s general “disfavor for self-dealing” and the design of a limited, law-governed presidency, Kalt asks.

In any event, no president has ever attempted a self-pardon, though Richard Nixon apparently considered it. After researching the issue, J. Fred Buzhardt, White House counsel for Watergate, concluded that the president had the power, and advised Nixon in July 1974 that the scandal could be “mooted” if the president pardoned everyone involved in Watergate, including himself. In August, just before he resigned, Nixon blustered about “put[ting] the special prosecutor out of business by leaving nothing unpardoned.”

Nixon wasn’t entirely in his right mind during this period: frequently drunk, incoherent, and raving against his enemies. His son-in-law Edward Cox had seen him pacing the halls at night, “talking to pictures of former presidents—giving speeches and talking to the pictures on the wall.” Cox thought suicide was a serious enough possibility to raise the issue of the Secret Service staying in the family quarters, to protect the president from himself. Nixon’s chief of staff, Gen. Alexander Haig, also worried the president might commit suicide, according to Woodward and Bernstein’s The Final Days. Haig recounted a disturbing conversation in which Nixon had said, “you fellows, in your business,” i.e., the military, “have a way of handling problems like this. Somebody leaves a pistol in the drawer.” “‘I don’t have a pistol,’ the President said sadly, as if it were one more deprivation in a long history of underprivilege.” Haig called Nixon’s doctors to warn them not to issue the president any more sleeping pills or tranquilizers.

Of course, Nixon eventually backed off the idea of pardoning his way out of Watergate and simply resigned. It says something that even in extremis, Nixon had enough of his wits about him to recognize that, legalities aside, a self-pardon was a crazy idea.

It would be nice to think that Donald Trump won’t turn out to be crazier than late-period Richard Nixon, but, just six months in, we’re learning to expect the unexpected. Luckily, if Donald Trump gets too ambitious with what he views as his “complete power to pardon,” there’s a constitutional remedy for that.

Many features of the 21st century presidency were beyond the Framers’ imaginations, but abuse of the pardon power was something they specifically considered. It was the subject of an interesting exchange between George Mason and James Madison at the Virginia ratifying convention in 1788. When the delegates turned to the first clause of Article II, section 2, Mason objected to the breadth of the president’s pardon power: “he may frequently pardon crimes which were advised by himself…. If he has the power of granting pardons before indictment, or conviction, may he not stop inquiry and prevent detection?” Madison’s rejoinder:

“There is one security in this case to which gentlemen may not have adverted: if the President be connected, in any suspicious manner, with any person, and there be grounds to believe he will shelter him, the House of Representatives can impeach him; [and] they can remove him if found guilty.”

Calls for Trump’s impeachment started even before his inauguration, and some of the grounds proposed have been pretty frivolous. This one wouldn’t be.