Today, The Oklahoman published an editorial that serves as a good example of how not to think about drone policy. According to The Oklahoman editorial board, a proposed drone weaponization ban was a solution in search of a problem, and concerns regarding privacy are based on unjustifiable fears. This attitude ignores the state of drone technology and disregards the fact that drones should prompt us to re-think privacy protections.

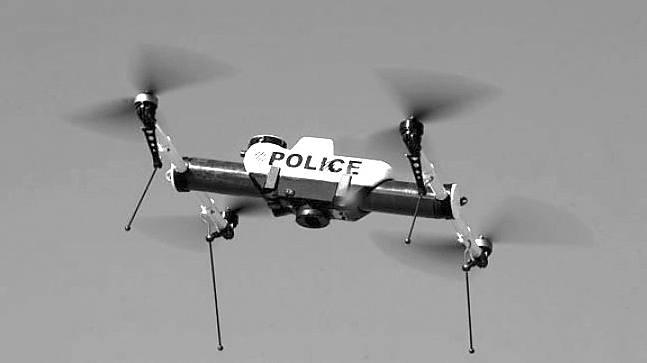

Weaponized drones are often thought of as tools of foreign policy, but technological advances mean that Americans should be keeping an eye out for armed drones on the home front. Yet, in the pages of The Oklahoman readers will find the following:

we know of no instance where Oklahoma law enforcement officers have used drones to shoot someone without justification. To ban the police from using weaponized drones appears a solution in search of a problem.

I’m not aware of police in Oklahoma using drones to shoot someone with justification, but that’s beside my main point. Oklahoman lawmakers shouldn’t have to wait for a citizen to be shot by a weaponized drone before considering regulations. It would be premature for legislators to consider teleport regulations or artificial intelligence citizenship bills. But weaponized drones are no longer reserved to the imagination of science fiction writers. They’re here.

Some states have taken steps to address weaponized police drones. Virginia and Oregon both ban weaponized police drones. Florida law defines police drones as an aerial vehicle that “Can carry a lethal or nonlethal payload.” North Dakota law allows police drones to be outfitted with Tasers. Whatever members of the Oklahoman editorial board think about these laws, they should at least consider the fact that lawmakers in Virginia, Oregon, Florida, and North Dakota didn’t wait for a police drone to shoot someone before pondering legislation.

In fact, one can make a convincing argument that weaponized drone legislation is especially worth considering given what happened in Dallas earlier this year. In July, Dallas police used a robot to kill a mass shooting suspect. It was the first such killing in the history of American policing. The Dallas police use of a robot to lethal effect ought to prompt lawmakers to get out in front of the issues associated with police using remote-controlled tools to kill citizens.

Fortunately, there has not been a significant push for police to have weaponized drones. Speaking before the Senate’s Judiciary Committee in 2013, Benjamin Miller, the Unmanned Aircraft Program Manager with the Mesa County, Colorado Sheriff’s Office, rejected police using lethal and non-lethal weapons on drones. Miller said that it would “absolutely not” be appropriate for police drones to be armed with lethal weapons. When it came to non-lethal weapons Miller noted, “in our experience, considering the risks of unmanned aircraft and then also the risks of use of less-than-lethal munitions, you know, such that they are, a bean bag round out of a shotgun, combining those two risks together is probably not the most responsible thing to do.”

As technology improves weaponized drones will become cheaper and more attractive to police departments. Police drones are comparatively rare at the moment, but this is mostly because of fiscal and technological constraints. We shouldn’t be in any doubt that police drones will be ubiquitous as soon as they become affordable and useful to most police departments.

At a time when the widespread use of police drones is in the near future it’s surprising that the Oklahoman editorial board is so seemingly dismissive about the privacy concerns, writing:

Kiesel [executive director, ACLU of Oklahoma] also suggested state law should limit law enforcement agencies’ ability to use drones in situations where residents normally have an expectation of privacy, saying warrants should typically be required in those situations.

On the surface, that doesn’t sound objectionable. Yet it would again be better if advocates of regulation could cite specific examples of abuse. The police can’t fly a drone into someone’s house, and there’s no reasonable expectation of privacy when a person is in a public space. So where are the areas where police can realistically fly a drone that are also areas where people have a reasonable expectation of privacy?

Here I think the editorial board is suffering from a lack of imagination. It’s true that under current Fourth Amendment doctrine police drones won’t usually be filming citizens where they have a reasonable expectation of privacy. But amid the proliferation of drones, it’s worth lawmakers considering how adequate the “reasonable expectation of privacy” standard is.

After all, in California v. Ciraolo (1986) and Florida v. Riley (1989), the Supreme Court held that you don’t have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the contents of your backyard observed from the air. It might be the case that some people won’t mind if police drones hover above their street recording their pool party, barbecue, or yard sale without a warrant, but I suspect that many not would be so happy.

Some lawmakers have recognized the worrying privacy implications of police drones. A handful of states including Florida, Idaho, Wisconsin, Indiana, Iowa, and Virginia have passed police drone warrant requirements. Proposed legislation in New Hampshire and Florida law extends the expectation of privacy for drone surveillance to private property where an individual is not observable from public space at ground level, “regardless of whether he or she is observable from the air.”

Drone technology is understandably attractive to law enforcement. When it comes to inspecting dangerous situations or searching for a suspect, drones can be valuable tools. Yet we should be wary of the privacy and safety concerns associated with police regularly using armed drones. Lawmakers who recognize these concerns should be praised for their foresight.