Donald Trump has said he wants to cancel President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and has implied he would do it on his first day in office. DACA allows young immigrants—known as Dreamers—who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children to live and work here temporarily

Trump recently softened his tone, saying he would try to “work something out” with Dreamers. But DACA probably won’t disappear overnight when Trump assumes office on January 20th in any case. Rather, it will slowly wind down as the immigrants’ temporary work permits expire. Here’s why and how that will happen.

How DACA operates

There are essentially three parts of DACA, which are detailed in a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) memorandum from Secretary Janet Napolitano. The first part is the deprioritization of removal of non-criminal unauthorized immigrants. Currently, the department relies on detailed priorities when deciding whether to remove a specific person. The DACA memo tells DHS agents to prevent Dreamers that they encounter “from being placed into removal proceedings or removed from the United States.”

The second part of DACA essentially formalizes that decision not remove them. DACA recipients apply for and are issued a Notice of Action I‑797 form (below) stating that removal action against them has been “deferred” for two years. Their information is entered into a database, and if it is checked against immigration databases, they are shown as lawfully present in the United States during that time. More than 800,000 young immigrants have enrolled in DACA and received such a letter.

Figure 1: DACA Form I‑797 Notice of Action

Source: Imgur

Finally, this receipt of deferred action authorizes the immigrants to request an employment authorization document (EAD) similar to the one below, which is also valid for two years. Under current law, any person in the United States—legally or illegally—can legally seek employment, but it is illegal for an employer to employ a noncitizen who is not authorized to work. Thus, an EAD is really about authorizing employers to make a hire, not about authorizing the DACA recipient to seek a job.*

What Trump can do about DACA

Trump could theoretically overturn the first part of DACA on day 1, authorizing agents to apprehend and remove DACA recipients. This is very unlikely. First of all, Congress has repeatedly enacted Homeland Security appropriations bills that instructed the president to “prioritize the identification and removal of aliens convicted of a crime by the severity of that crime.” Second, while it is possible that Trump could ignore this, he has stated that he will indeed continue to prioritize criminals (one Trump advisor has suggested that immigrants arrested for, but not yet convicted of, serious offenses would also be prioritized). Third, Trump’s vague promise to “work something out” implies at least some unwillingness to go out of his way to deport Dreamers. Fourth, Trump’s unrealistic vow to deport 2 million criminals makes it unlikely he will waste precious resources on low priority, non-criminal cases.

Trump could easily cancel the second part of DACA on day 1, telling U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to cease accepting applications for I‑797 deferred action forms. These forms are technically valid for two years, but they clearly state that they were issued as part of DACA. Deleting DACA recipients from ICE databases that list them as “lawfully present” could be more time-consuming, but probably not technically impossible.

Figure 2: DACA-based Employment Authorization Document (EAD)

Source: WangLawOffice

Because employment authorization is dependent on a grant of deferred action, canceling part 2 of DACA would legally end part 3 as well. But in practice, the administration cannot prevent DACA recipients from working until their employment authorization document expires. As can be seen in the EAD above, nothing on the physical document indicates that it was issued under DACA, and employers are legally obligated to accept any facially valid, non-expired form of identification issued by the federal government. There is no electronic way to cancel an EAD, and discriminating against job applicants simply because they are using an EAD is illegal.*

The Obama administration has showed how difficult ending DACA quickly will be

President Obama actually tried to cancel certain DACA EADs in 2015. In 2014, two years after DACA was initially implemented, the Obama administration declared it would expand DACA to a broader group of immigrants and issue 3‑year EADs. When several states sued to prevent implementation of that memo and the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans memo, a judge imposed an injunction against the expanded DACA in February 2015. The Obama administration initially misinterpreted his order and incorrectly continued to issue 3‑year EADs as renewals to the initial group of DACA recipients.

The administration sent or resent 2,600 three-year EADs to DACA recipients after the judge’s order in February. Because the expiration date on the EAD prevented the administration from halting DACA recipients’ employment authorization electronically, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) had to individually recoup them. DHS sent out 2,600 letters and called each recipient to inform them that they would be replacing 3‑year EADs with 2‑year EADs. USCIS officials also apparently made visits to some recipients’ “listed address” to collect the 3‑year EADs in person. DHS also said, “If you fail to return your card, USCIS will terminate your DACA and all employment authorizations effective July 31, 2015.” It is not clear how they planned to effectuate this termination.

Ultimately, USCIS failed to recover 22 cards, or failed to receive good cause for not receiving them. As a result, those 22 individuals were “terminated from DACA.” The agency says termination involved sending the following letter to DACA recipients:

Any DACA-based EAD you received (including your recently issued 2‑year EAD) is now invalid. You must return all DACA-based EADs to USCIS immediately. Fraudulent use of your EADs could result in a referral to law enforcement. You are still required to return your invalid EADs to USCIS. As noted in your Notice of Intent to Terminate, USCIS may consider failure to return your invalid EADs a negative factor in weighing whether to grant any future requests for deferred action or any other discretionary requests.

However, this letter failed to provide a statute under which the DACA recipient could be prosecuted, and the immigration statute and two criminal statutes relating to misuse of documents or fraudulent use of documents do not appear to prohibit use of a genuine EAD issued legally to the person who is using it.* In any case, there would be no practical constraint on these DACA recipients seeking employment, since an employer that was unaware of the cancellation could continue to employ them lawfully.* Moreover, there is no indication that these 22 immigrants were in fact removed from the country.

In the end, even when offering to replace EAD cards, DHS needed to send agents to recipients’ homes, and 1 percent of recipients still failed to cooperate. It is easy to imagine how difficult it would be if there was no offer of a replacement. While the fact that home visits were made demonstrates that DHS does have the knowledge and ability to track down DACA recipients in certain cases, it is likely that as soon as any apprehensions were made, other DACA beneficiaries would move.

How DACA would naturally wind down

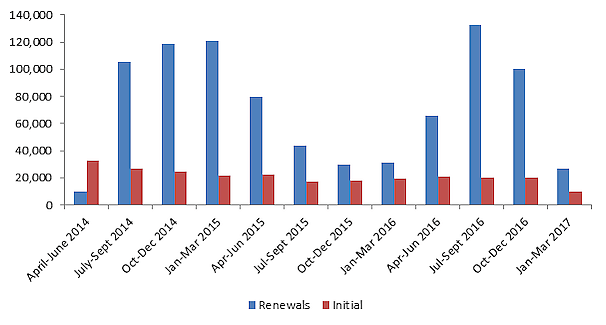

Even if it wanted to, the Trump administration would likely be dissuaded from ending DACA immediately by the practicalities of cancelling all 800,000 EADs alone. But it makes especially little sense to do this when a majority of the EADs will expire within a year of Trump assuming office in any case. The Obama administration has since 2014 made public quarterly breakdowns of when DACA recipients renewed their status or received their status for the first time. Figure 3 provides those figures with projections for the last three quarters, based on the typical rate of approvals for initial applications and the number of 2‑year renewals during the same quarters two years prior.

Figure 3: Timeline of DACA Approvals—Initial and Renewals—April 2014 to March 2017

Source: USCIS Data Set: Form I‑821D Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. July 2016 to March 2017 are projections based on the number of two-year renewals in those months in 2014 and 2015. January to March 2017 is projected based on the percentage of days of the current administration’s term.

This timeline of DACA approvals allows for the creation of a rough timeline of DACA EAD expirations, provided in figure 4. More than 85 percent of all DACA EADs are 2‑year authorizations. Another 108,000 are 3‑year authorizations that were issued in late 2014 and early 2015. Unfortunately, the 3‑year EADs will expire for most receipients in December 2017 or January 2018—sooner than if they had been issued two-year renewals, which they could have renewed in December 2016 and early January 2017, allowing for an extra year of authorization. As a result, there will be a more constant stream of DACA expirations than there were DACA approvals.

Figure 4: Projected DACA Expirations by Quarter

Source: Author’s calculation based on USCIS DACA Approval Figures. See figure 3 explanation.

Approximately 314,000 DACA recipients will lose DACA EAD authorization in 2017—about 38 percent of all DACA applicants. Another roughly 467,000 will lose authorization in 2018—about 115,000 of those will happen in the first quarter of 2018, meaning that DACA will be half over by March 2018.

Figure 5: Projected DACA Expirations by Year

Source: Author’s calculation based on USCIS DACA Approval Figures.

A couple of uncertainties are present in this analysis. First, the administration allows DACA renewal applications up to 6 months in advance, and some DACA renewal approvals occurred before the initial 2‑year period ended, meaning that the administration issues a determination before the new period begins in some cases. In other cases, the administration issued renewals after the 2‑year period was over. Thus, it is possible that the periods of DACA authorization could continue somewhat beyond the 2‑year mark of their approval (though the data is divided into 3‑month chunks, so it cannot be far off). Second, for the same reason, it is possible that the current administration could issue pre-approved EADs before the end of its term. This would obviously require ramping up the already-high current pace of renewals.

Worst case and best case scenario for DACA recipients under President Trump

The worst case scenario for DACA recipients would be that the Trump administration stops accepting new DACA applications and eliminates any kind of priorities for removal, allowing agents to apprehend any unauthorized immigrant that they meet. The administration could further create panic in the immigrant community by targeting certain DACA recipients for arrest, using the address information that they provided as part of their application. At the same time, the Trump administration could potentially threaten to prosecute employers or the immigrants themselves if they use their EADs. This would create chaos for employers and workers, as no employer would know if the EAD they were reviewing was valid.

At the other extreme, the Trump administration could continue the current priorities for removal and allow current recipients of DACA to use their EADs until they expire, while not accepting new applications or renewals. This would be the least controversial and most practical decision that would also be consistent with Trump’s campaign promises.

*The contents of this article are intended to convey general information only and not to provide legal advice or opinions. No action should be taken in reliance on the information contained in this article. If the reader is in need of legal advice, they should contact a licensed attorney.