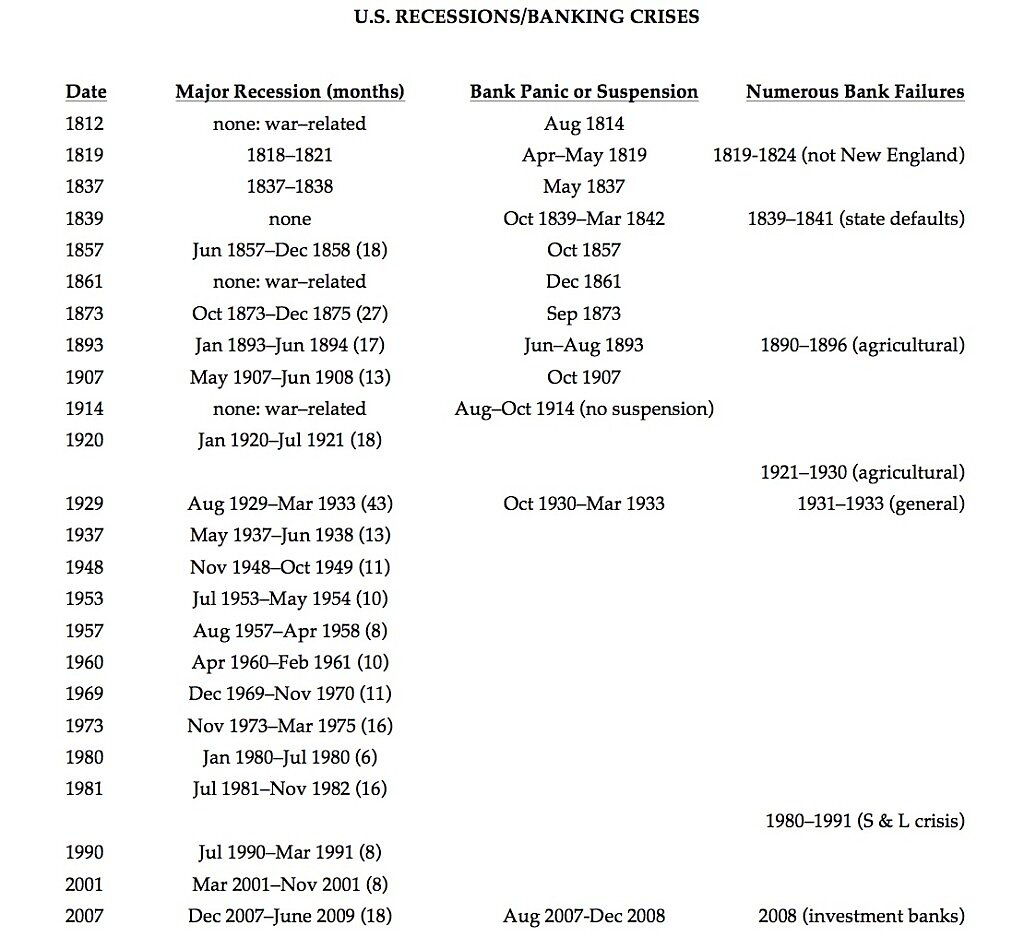

I have never been entirely satisfied with how either economists or historians identify and date past U.S. recessions and banking crises. Economists, as their studies go further back in time, have a tendency to rely on highly unreliable data series that exaggerate the number of recessions and panics, something most strikingly but not exclusively documented in the notable work of Christina Romer (1986b, 1989, 2009). Historians, on the other hand, relying on more anecdotal and less quantitative evidence, tend to exaggerate the duration and severity of recessions. So I have created a revised chronology in the table below. From the nineteenth century to the present, it distinguishes between three types of events: major recessions, bank panics, and periods of bank failures. I have tried to integrate the best of the approaches of both economists and historians, using them to cross check each other. My chronology therefore differs in important ways from prior lists.

One of the table’s benefits is that it gives a visual presentation of which recessions were accompanied by bank panics and which were not. Equally important, it distinguishes between bank panics and periods of significant numbers of bank failures. These two categories are often confused or conflated, and yet this distinction is critical. Not all bank panics (periods of contagious runs and sometimes bank suspensions) were accompanied by numerous bank failures, nor were all periods of numerous failures accompanied by panics.

Among other advantages, the table helps highlight how sui generis the Great Depression was. Not only does it have the longest downturn (43 months), but it also is one of the few depressions accompanied by both bank panics and numerous bank failures. Once the Great Depression is thrown out as a statistical outlier, we observe no significant change in the frequency, duration, or magnitude of recessions between the period before and the period after that unique downturn. Given that the Great Depression witnessed the initiation of extensive government policies to alleviate depressions and that the Federal Reserve had been created fifteen years earlier explicitly to prevent such crises, this overall historical continuity with a single exception indicates that government intervention and central banking has done little, if anything, to dampen the business cycle.

There has been a dramatic elimination of bank panics, at least until the financial crisis of 2007–2008, but the timing suggests that deposit insurance more than the Federal Reserve deserves the credit. Furthermore, note that more outbreaks of numerous bank failures occurred in the hundred years after the Federal Reserve was created than the hundred years before, with the Federal Reserve presiding over the most serious case of all: the Great Depression.

Because my table departs from previous lists and dating, in what follows, I explain the most important differences for each of the three categories. At the end of the post is a list of the most useful references I consulted.

Recessions

I have almost entirely confined the list of major recessions to those constituting part of a standard business cycle, omitting periods of economic dislocation resulting from U.S. wars or government embargoes. For the number and dating of recessions from 1948 forward, I have exclusively followed the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). But prior to 1929, the NBER notoriously exaggerates the volatility of the U.S. economy. Moreover, between 1929 and 1948, the NBER reports a post-World War II recession lasting from February to October 1945 that no one was aware of at time, as easily confirmed by looking at the unemployment data as well as contemporary writings. Richard K. Vedder and Lowell E. Gallaway (1993) pointed out in their neglected study of U.S. unemployment that this alleged postwar recession is a statistical artifact that varies in severity with the regular comprehensive revisions of GNP/GDP estimates by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The BEA’s original estimates showed only a minor downturn, subsequent revisions converted it into a major downturn, and the latest comprehensive revision of 2013 have reduced its magnitude, although not to the level of the BEA’s original estimates.

For the pre-1929 period, therefore, I have only listed recessions that can be documented with unemployment data or more traditional historical evidence. The unemployment data I have employed are the revisions of both J. R. Vernon (1994) and Romer (1986b). I have still accepted NBER dating, which only goes back to 1857, for those pre-1929 recessions that I consider genuine, with the notable exception of 1873. In that case, the NBER dating (based on the Kuznets-Kendrick series) of a 65-month recession is so inconsistent with other evidence that it was even questioned by Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz in their Monetary History (1963). This is one of the most striking cases in which some observers at the time and many economists today have confused mild secular deflation with a depression – a confusion exposed by George Selgin in Less than Zero (1997). Even the Kuznets-Kendrick estimates show no decline in real net national product during this recession, and an acceleration of its growth after 1875. I have therefore accepted Joseph H. Davis’s (2006) revised dating, shortening this recession to not more than 27 months, and probably less if he had attempted a monthly rather than just an annual revision of the depression’s end point.

Estimates of U.S. GDP prior to the Civil War are even more problematic, making precise monthly dating of recessions impossible. So I have relied upon the consensus of standard historical accounts along with the GDP statistics in Historical Statistics: Millennial Edition (Carter 2006) to determine what qualifies as an actual recession and its annual dating. The one case where I diverge from some (but not all) mainstream historical accounts is the alleged recession during the banking crisis that began in 1839, after the recovery from the 1837 recession. As Friedman and Schwartz (1963), Douglass C. North (1961), and Peter Temin (1969) have all noted, estimates of real GDP growth over the next four years are quite robust. Thus, 1839–1843 appears to be another case were deflation (in this case, quite severe) is confused with depression.

Bank Panics

The number of bank panics is also often exaggerated. For the post-Civil War period, many authors follow the enumeration first compiled by O. M. W. Sprague (1910), and some even add in a few more. But Elmus Wicker (2000) has persuasively demonstrated that the alleged Panics of 1884 and 1890 were really only incipient financial crises nipped in the bud by the actions of bank clearinghouses. For the pre-Civil War period, especially egregious in its listing of panics is the widely cited work of Willard Long Thorp (1926), which even mistakenly attributes to the United Sates panics that affected only England (those in 1825 and 1847).

I have confined my own list to those panics that Andrew J. Jalil (2015) in his comprehensive survey of previous literature defines as “major,” with two exceptions. First, I have omitted the very minor economic contraction of 1833, following Andrew Jackson’s phased withdrawal of government deposits from the Second Bank of the United States, since the impact on banks was almost entirely confined to the Second Bank and its branches. Second, I have included the more pronounced global financial crisis at the outbreak of World War I, in which the U.S. stock market was shut down for four months, although the emergency currency authorized under the Aldrich-Vreeland Act prevented bank suspensions. The monthly dating of other panics listed is confined to the period during which major suspensions or runs occurred and does not always reflect how long banks suspended, which for the War of 1812 was until January 1817.

Bank Failures

Bank panics, even when accompanied by numerous suspensions (or what Friedman and Schwartz prefer to call “restrictions on cash payments” to distinguish them from government suspensions of redeemability), do not always result in a major number of bank failures.

For instance, Calomiris and Gorton report the failure of only six national banks out of a total of 6412 during the Panic of 1907, or less than 0.1 percent. Of course the Panic of 1907 was concentrated among state banks and trust companies. Unfortunately, as far as I can tell, there are no good time series on the failures of state banks for the period prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve. Yet there were over 12,000 state banks at the outset of the Panic of 1907. One very fragmentary and incomplete estimate of total bank suspensions (rather than failures) in Historical Statistics (1975), including both state and national banks, puts the number during that panic at 153. Even if all suspensions had resulted in failures, which of course did not happen, we still have a failure rate of 0.7 percent for all commercial banks.

Confusion of bank suspensions with bank failures can even infect serious scholarly work. For example, in Michael D. Bordo and David C. Wheelock (1998), charts meant to show bank failures are instead clearly depicting statistics on the annual number of bank suspensions. Similarly, periods of numerous bank failures do not always coincide with bank panics, as the S&L crisis dramatically illustrates. So it is crucial to distinguish between periods of panics and failures, although specifying the latter requires judgment calls. For the monthly number of national bank failures prior to the Fed’s creation, I have depended heavily on Comptroller of the Currency (1915), v. 2, Table 35, pp. 66–103.

Summary

To be sure, banking in the United States has never been fully deregulated. Even from 1846 until 1861, under the Independent Treasury during the alleged free-banking period, when there was almost no significant national regulation of the financial system, state governments still imposed extensive, counter-productive banking regulation. This fact obviously complicates any comparison of the periods before and after the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1914. Nonetheless, such a comparison offers more than a prima facie case against the Fed’s success at either stabilizing the U.S. economy or preventing banking crises. In short, the widespread belief among economists, historians, and journalists that the Federal Reserve was an essential, major improvement appears to be no more than unreflective faith in government economic management, with little foundation in the historical evidence.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Graham Newell and Kurt Schuler for their invaluable assistance and comments while preparing this table. Any remaining errors or oversights are my responsibility.

[Cross-posted from Alt‑M.org]