“GOP Agrees Bush Was Wrong to Invade Iraq, Now What?”—that’s how the US News headline put it last week. A good question, because it’s not at all clear what that grudging concession signifies. It’s nice that 12 years after George W. Bush lumbered into the biggest foreign policy disaster in a generation, the leading Republican contenders are willing to concede, under enhanced interrogation, that maybe it wasn’t the right call. It would be nicer still if we could say they’d learned something from that disaster.

Alas, the candidates’ peevish and evasive answers to the Iraq Question didn’t provide any evidence for that. Worst of all was Jeb Bush’s attempt to duck the question by using fallen soldiers as the rhetorical equivalent of a human shield. Ohio governor John Kasich flirted with a similar tactic—“There’s a lot of people who lost limbs and lives over there, OK?”—before conceding, “But if the question is, if there were not weapons of mass destruction should we have gone, the answer would’ve been no.”

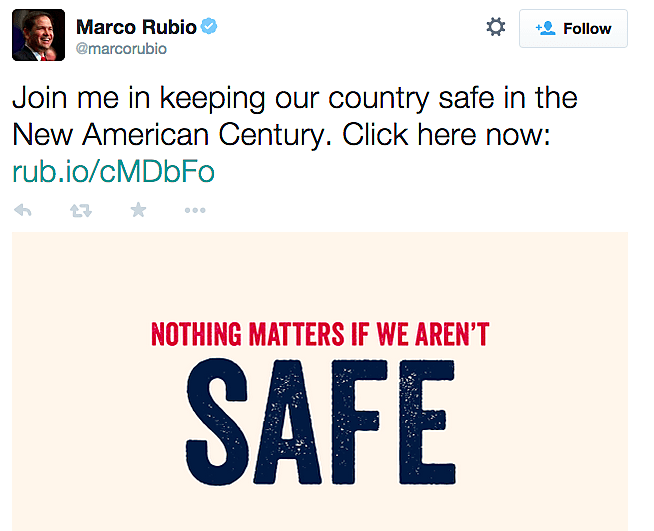

That’s how most of the GOP field eventually answered the question, with some version of

the “faulty intelligence” excuse. We thought Saddam Hussein had stockpiles of chemical

and biological weapons and was poised for a nuclear breakout; it was just our bad luck

that turned out not to be true; so the war was—well, not a “mistake,” insists Marco Rubio, just, er—whatever the word is for something you definitely wouldn’t do again if you had the

power to travel back in time. As Scott Walker, who’s been studying up super-hard on

foreign policy, explained: you can’t fault President Bush: invading Iraq just made sense, based on “the information he had available” at the time.

Well, no—invading Iraq was a spectacularly bad idea based on what we knew at the time. If we’d found stockpiles of so-called WMD, it would still have been a spectacularly bad idea. Saddam’s possession of unconventional weapons was a necessary condition in the Bush administration’s case for war, but it wasn’t—or shouldn’t have been—sufficient to make that case compelling, because with or without chemical and biological weapons, Saddam’s Iraq was never a national security threat to the United States.

Put aside the fact that, as applied to chem/bio, “WMD” is a misnomer; assume for the sake of argument that President Bush’s claim that “one vial, one canister, one crate” of the stuff could “bring a day of horror like none we have ever known” was an evidence-based, good-faith assessment of those weapons’ potential, instead of a ludicrous and cynical exaggeration. Even so, you’d still have to show that Saddam Hussein was so hell-bent on hitting the U.S., he’d risk near-certain destruction to do it.

There was never any good reason to believe that. This, after all, was a dictator who, during the 1991 Gulf War, had been deterred from using chemical weapons against US troops in the middle of an ongoing invasion. As then-Secretary of State James Baker later explained, the George H.W. Bush administration:

made it very clear that if Iraq used weapons of mass destruction, chemical weapons, against United States forces that the American people would demand vengeance and that we had the means to achieve it. … we made it clear that in addition to ejecting Iraq from Kuwait, if they used those types of weapons against our forces we would in addition to throwing them out of Kuwait, we would adopt as a goal the elimination of the regime in Baghdad.

Eleven years later, as the George W. Bush administration pushed for another war with Iraq, there wasn’t any convincing evidence that Saddam Hussein had, in the interim, warmed up to the idea of committing regime suicide through the use of CBW. Even the flawed October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) prepared during the run-up to the Iraq War vote concluded that “Baghdad for now appears to be drawing a line short of conducting terrorist attacks with conventional or CBW against the United States, fearing that exposure of Iraqi involvement would provide Washington a stronger cause for making war.”

By that time, with Bush 43 sounding the alarm about Iraq’s “growing fleet of manned and unmanned aerial vehicles that could be used to disperse chemical or biological weapons across broad areas [including] missions targeting the United States,” it should have been apparent that the case for war rested on a series of imaginary hobgoblins. As Jim Henley put it a couple of years ago, “In the annals of projection, the US claim that Saddam was building tiny remote-controlled death planes wins some kind of prize.”

What if the Iraqi dictator instead passed off those weapons to terrorists, “secretly and without fingerprints”? In the 2003 State of the Union, that’s what President Bush argued Saddam just might do: “imagine those 19 hijackers with other weapons and other plans, this time armed by Saddam Hussein.” But the notion that Hussein was likely to pass chemical or biological weapons to Al Qaeda was only slightly less fantastic than the scenario that had him crop-dusting US cities with short-range, Czech-built training drones. As my colleague Doug Bandow pointed out at the time: “Baghdad would be the immediate suspect and likely target of retaliation should any terrorist deploy [WMD], and Saddam knows this.”

I made similar arguments two weeks before the war in a piece called “Why Hussein Will Not Give Weapons of Mass Destruction to Al Qaeda”:

The idea that Hussein views a WMD strike via terrorist intermediaries as a viable strategy is rank speculation, contradicted by his past behavior. Hussein’s hostility toward Israel predates his struggle with the United States. He’s had longstanding ties with anti-Israeli terror groups and he’s had chemical weapons for over 20 years. Yet there has never been a nerve gas attack in Israel. Why? Because Israel has nuclear weapons and conventional superiority, and Hussein wants to live. If he’s ever considered passing off chemical weapons to Palestinian terrorists, he decided that he wouldn’t get away with it. He has even less reason to trust Al Qaeda with a potentially regime-ending secret.

In its 2004 after-action reassessment of the administration’s case for preventive war, the Carnegie Endowment concluded:

there was no positive evidence to support the claim that Iraq would have transferred WMD or agents to terrorist groups and much evidence to counter it. Bin Laden and Saddam were known to detest and fear each other, the one for his radical religious beliefs and the other for his aggressively secular rule and persecution of Islamists. Bin Laden labeled the Iraqi ruler an infidel and an apostate, had offered to go to battle against him after the invasion of Kuwait in 1990, and had frequently called for his overthrow. … the most intensive searching over the last two years has produced no solid evidence of a cooperative relationship between Saddam’s government and Al Qaeda. ….the Iraqi regime had a long history of sponsoring terrorism against Israel, Kuwait, and Iran, providing money and weapons to these groups. Yet over many years Saddam did not transfer chemical, biological, or radiological materials or weapons to any of them “probably because he knew that they could one day be used against his secular regime.”

In the judgment of U.S. intelligence, a transfer of WMD by Saddam to terrorists was likely only if he were “sufficiently desperate” in the face of an impending invasion. Even then, the NIE concluded, he would likely use his own operatives before terrorists. Even without the particular relationship between Saddam and bin Laden, the notion that any government would turn over its principal security assets to people it could not control is highly dubious. States have multiple interests and land, people, and resources to protect. They have a future. Governments that made such a transfer would put themselves at the mercy of groups that have none of these. Terrorists would not even have to use the weapons but merely allow the transfer to become known to U.S. intelligence to call down the full wrath of the United States on the donor state, thereby opening opportunities for themselves.

You don’t have to “know what we know now” to recognize the poverty of the case for war. You just had to know what we knew then.

Even so, it’s possible that GOP hawks have learned something from the Iraq debacle, however loathe they are to admit it. Like Saddam’s Iraq, the Syrian and Iranian regimes have long had unconventional weapons and links to terrorist proxies. But I haven’t heard even Lindsey Graham or Marco Rubio invoke the risk of terrorist transfer to make the case for war with Iran or Syria. Perhaps that’s because it’s as unpersuasive an argument now as it should have been then.

Besides, maybe it’s asking too much to expect professional politicians to depart entirely from the sentiments of the people they want to vote for them. A recent Vox Populi/Daily Caller poll asked Republican voters in early primary states: “Looking back now, and regardless of what you thought at the time, do you think it was the right decision for the United States to invade Iraq in 2003?” Nearly 60 percent of them answered in the affirmative. The GOP’s 2016 contenders may not have good answers to the Iraq Question, but, apparently, they’re miles ahead of their constituents.