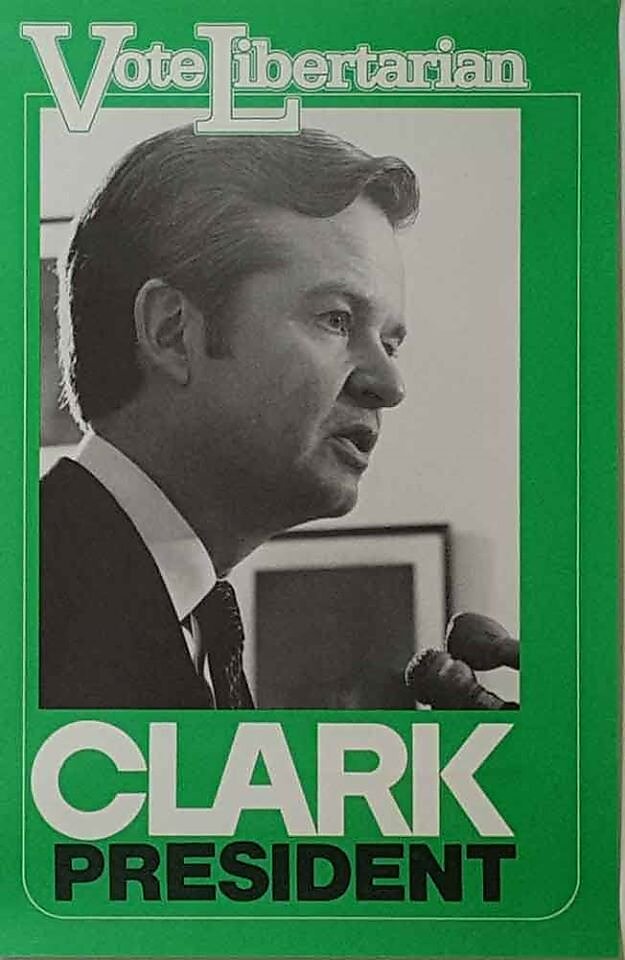

Ed Clark, the 1980 Libertarian Party presidential nominee, turns 90 years old on May 4. Now that Rep. Justin Amash has thrown his hat into the ring for the 2020 nomination, I thought I’d offer some reminiscences about the earlier campaign.

In my misguided youth I was a teenage Young Democrat, a College Republican, and a young adult Libertarian Party activist, before I gave up politics for ideas and policy. In 1978, a few years out of college, I left my conservative job to become co-manager of Ed Clark’s campaign for Governor of California on the Libertarian ticket. (He was actually on the ballot as an independent because it was much easier to get ballot status that way.)

As I wrote in the Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, Clark was a corporate attorney in New York and Los Angeles. He opposed the Vietnam War while remaining a Republican, but when President Richard Nixon imposed wage and price controls in 1971, he joined the Libertarian Party and quickly became a member of its national committee and California State Chair. As one of the most successful and articulate professionals in the fledgling party, he was persuaded to run for governor in 1978.

A political campaign with co-managers sounds like a recipe for disaster. It wasn’t, for two reasons: because libertarian impresario Ed Crane hovered over the campaign as Chairman and guiding light, and because the two managers had entirely different skills. I was the words-and-policy guy, and Bob Costello was the people-and-organization guy, and even in a two-desk office we actually managed to stay out of each other’s way.

Clark spent two months campaigning, with Bob and me scrambling to set up schedules. Mostly he stayed in the big cities of San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Sacramento, plus one trip through Bakersfield, Fresno, and Stockton in the Central Valley. We had enough money for radio ads. They were very policy-oriented, addressing school choice, busing, victimless crimes, the antigay Briggs Initiative, and the tax-cutting Proposition 13, which only Clark of all the gubernatorial candidates had supported enthusiastically before it passed overwhelmingly. We also got enough last-minute money to run some full-page newspaper ads and put together a half-hour interview (with then-Reason columnist Tom Hazlett) that ran in major markets. (I wrote recently on Facebook about how I also directed actor Orson Bean in a couple of Clark commercials.)

In the end Clark got 5.46 percent of the vote, which we thought was pretty good for a candidate no one had heard of before the campaign and who had minimal money. We got the most votes in populous Los Angeles and Orange counties, but Clark’s percentages in both counties were below the state average. He did best in rural Nevada County, where there was a strong local organization, and in Kern County, where the Bakersfield Californian endorsed him and then actually ran news stories about him for a week — as newspapers always do for the Republican and Democratic candidates. And even one on-the-trail feature story, which began (if I recall) “He has the charisma of John F. Kennedy and the verbal agility of Bill Buckley.” Which might just be a description that no candidate could live up to. With that minimal coverage he got almost twice his statewide average in Kern County. Good thing we made that one trip to Bakersfield, where he met with the paper’s editorial board. He also did well in the San Francisco suburbs and in the northern counties of Humboldt, Mendocino, and Trinity — known as the “Emerald Triangle” for their widespread pot growing. Probably should have taken a campaign swing up that way.

Anyway, Clark’s 377,960 votes made him the star of the Libertarian Party (along with Dick Randolph of Alaska, who became the party’s first elected legislator that year). People immediately started wooing him to run for president. After he announced, he had a vigorous challenge for the nomination from businessman Bill Hunscher, but he ended up winning about 2/3 of the delegates’ votes.

One of the biggest challenges for an independent or third-party candidate is fundraising. The government doesn’t fund your convention and your campaign (as it did for the Republicans and Democrats), and it limits individual contributions (to $1,000 then, $2,800 now). That’s why the only really successful independent presidential candidate since the passage of the Federal Election Campaign Act was celebrity billionaire Ross Perot. In 1980 the LP partially solved that problem by persuading David Koch, then a little-known New York executive, to serve as the vice-presidential nominee so that he could make large contributions to the campaign. And he did: about $3 million. That would be close to $10 million now, but it was worth even more because at the time networks would sell 5‑minute ads at a “program” rate, which was much cheaper than the rate for a 30-second commercial. Koch’s money allowed the campaign to purchase 47 network television ads during the fall. I wish I could find some of those professionally made ads. You can find a 13-minute video made for house parties here, but it’s not nearly as engaging.

Clark went back to his corporate law job after the September 1979 convention, campaigning mostly on the weekends at Libertarian state conventions. Beginning in July he took a leave and campaigned full time. I joined the campaign as Research Director around that time. The campaign had several dozen staff members in the Washington, DC, headquarters, and also one paid state coordinator in 20 or so states. Clark met with numerous newspaper editorial boards, appeared on a few network television programs (cable was in its infancy) and lots of local broadcasts, spoke to college audiences, Rotary Clubs, and such high-profile venues as the Detroit Economic Club and the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. Clark’s name appeared on the ballot in all 50 states, plus the District of Columbia and Guam. He was the first third-party candidate to appear on every possible ballot since Theodore Roosevelt in 1916.

The Clark campaign may have been the most intellectual and wonkish presidential campaign ever. Clark’s campaign book, A New Beginning, reflected the contributions of Ralph Raico, Joan Kennedy Taylor, Chris Hocker, Sheldon Richman, Tom Palmer, Roy Childs, Ed Crane, and me. I wrote an 80-page White Paper on Tax and Spending Reduction and edited similar papers on foreign and military policy, education, and Social Security reform. We also published about a dozen position papers, some written by respected scholars. More than one major journalist told us that we had the most substantive policy papers, though I don’t recall them telling their readers that.

Clark got good press reviews, just not enough of them. One Washington Post reporter — Elisabeth Bumiller, who is now the Washington Bureau Chief of the New York Times — wrote that Clark ” has been called an ‘eminently reasonable radical’ but looks as wholesome as Beaver Cleaver’s father.” T. R. Reid of the Post, who traveled with us for a couple of days, reported on “the 550 people who turned out on a snowy night [in Missoula, MT] this week to listen to Clark.” He was endorsed by the Peoria Journal-Star — small, but still a rarity for a third-party candidate — and by lefty columnist Nicholas von Hoffman in the New Republic.

Clark’s campaign was hindered by an unexpected obstacle: Rep. John Anderson (R‑Ill.), a moderate Republican, ran for the GOP nomination; clashed with the other candidates and voters at town halls over issues such as tax cuts, gun control, and the ERA; got rave coverage from the New York Times to Doonesbury and Saturday Night Live for his un-Republican approach; and decided to run as an independent. He occupied a similar space as Clark: buttoned-down but unconventional and broadly “fiscally conservative and socially liberal.” As a result he got a lot of the media attention that the Clark campaign had expected would go to a third alternative running against two candidates then perceived as unpopular, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. I think that severely limited the campaign’s upside.

In the summer Clark had been traveling with one 18-year-old body/baggage/phonecalling aide. Around Labor Day, having finished all that writing and editing, I doubled the entourage by going on the road with the candidate. I was supposed to advise him on policy and write the occasional new speech, though in fact he knew his policy brief pretty well and didn’t much care for new speeches. Some people say that libertarians aren’t generally good at politics because they tend to be introverted intellectuals (“INTJ”). In two months of traveling with Clark I met only one Libertarian who could work a room, and it wasn’t our presidential candidate, it was Dick Randolph, an insurance salesman who had been a top officer of the Jaycees before becoming the first Libertarian legislator.

The election was perceived to be close. In the end, it wasn’t: Reagan beat Carter 51–41 and won 489 electoral votes. But the polls were very close right up to the election. Clark got 920,000 votes, 1.06 percent. It was the largest vote total for a Libertarian nominee until 2012, the largest percentage until 2016. In both elections it was two-term governor Gary Johnson who exceeded Clark’s totals.

The Clark campaign didn’t turn the United States into a three-party system, which was one of its stated goals. It did establish the Libertarian Party as the largest and best organized third party in the country, though the party had trouble maintaining its status after 1980. It produced the best set of policy analysis that modern libertarians had seen. It brought together many talented libertarians, many of whom went on be mainstays of libertarian activism and scholarship for a generation or more.

Happy birthday, Ed Clark.