An article in yesterday’s New York Times frets that 11.6 percent of people in China suffer from type two diabetes and that half the country’s population may have prediabetic blood glucose levels. How has this come to pass?

Experts have blamed many factors: the introduction of high-calorie Western diets and fast food, more travel by car, sedentary factory jobs replacing farm labor, and families who spoil the one child that most are allowed to have.

Let me offer this paraphrasing: The Chinese people have a great variety of food options, more money, and better jobs. The effect of this increase in wealth is that there are now 114 million Chinese people who are too rich for their own good. Just a little bit of context makes clear what an incredible victory this diabetes “epidemic” represents for China. Fifty years ago, while Americans were watching new episodes of Leave it to Beaver in primetime, up to 45 million Chinese people died in a famine caused by inept central planning and a horrific ideological experiment. China’s post-Mao economic reforms began in 1978, and global economic engagement over the last fifteen years especially, have improved quality of life not only in China but around the world. Today, hundreds of millions of Chinese have the ability to sicken themselves overindulging in tasty foreign food if they want to.

Unfortunately, there is a growing movement of academics, activists, and international civil servants concerned about the dangers of “non-communicable diseases” in developing countries. They blame “Western” lifestyles, capitalism, and trade for exposing people to cigarettes, alcohol, and junk food. They worry that Coca-Cola is making Mexicans fat and that Bolivians growing fad health-food quinoa are dropping the Andean staple from their own diets in favor of less healthy alternatives.

The paternalistic impulse to protect people from the consequences of liberty and prosperity, even denying them liberty and prosperity for their own good, is not a new idea, of course. Equally well established is the particularly troubling tendency to mix this paternalism with a romantic view of foreign poverty. In 1754, Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote that disease is a product of modern civilization:

When we think of the good constitution of the savages, at least of those whom we have not ruined with our spirituous liquors, and reflect that they are troubled with hardly any disorders, save wounds and old age, we are tempted to believe that, in following the history of civil society, we shall be telling also that of human sickness.

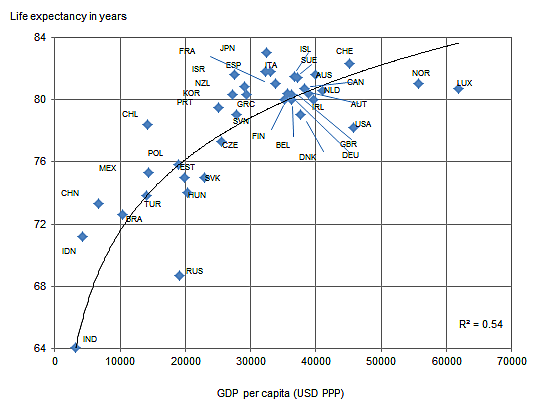

To be fair, most people concerned about the deleterious effect of choice and wealth in China are also alarmed by similar trends in the United States. Rather than echo Rousseau’s contention that human progress is the cause of disease, critics would do well to examine the empirical evidence. If you really care about the health of people in China, I impore you to consider the lesson taught by this graph here: