In March, at the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdowns, the CDC reported: “In other countries, those places who closed school (e.g., Hong Kong) have not had more success in reducing spread than those that did not (e.g., Singapore).” Today, that the default for schools should be in-person instruction, especially for younger students, has been reinforced myriad times. Add to this the release of COVID vaccines, and many jurisdictions prioritizing teachers to receive them, and you would expect public schools across the nation to be welcoming kids back in droves.

Not so fast. In Chicago, under the direction of their union, thousands of teachers refused to return to in-person instruction yesterday. In Fairfax County, Virginia, the teacher association is resisting returning to in-person instruction even after all teachers – but not students – have been vaccinated. These are continuations of re-opening refusals from unions that we have seen throughout the pandemic.

I’ve pointed out before that the national COVID response has shone a brilliant light on the long-existing necessity of school choice. All children have different needs and face different dangers – the child with a learning disability may need in-person education, the one living with elderly grandparents may need to stay home – but too often a district or school can offer just one option. Of course, teacher unions have long been the most prominent opponents of school choice, which would seriously threaten their monopolies on labor.

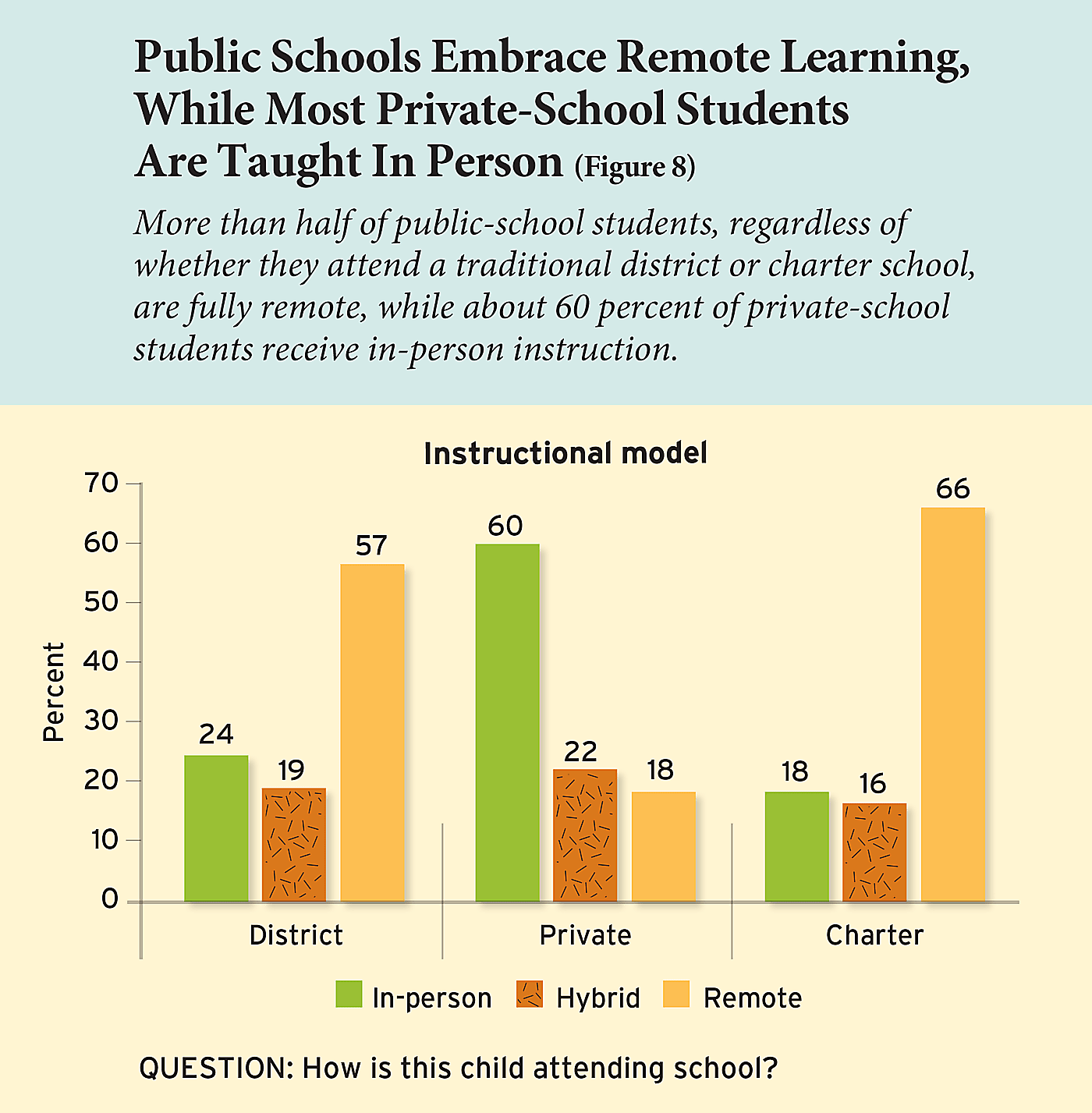

What we have too often missed is that teachers may need choice as much as children do. While the evidence points to the overall safety of reopening schools in-person – and private schools have done it in droves (see below) – there is certainly some risk in returning face-to-face. This is especially true for high-risk groups, such as older teachers or those with underlying conditions. But were public opinion to swing to districts providing in-person schooling for all students, those teachers would often be out of options other than to quit or retire. And right now, public school teachers who might prefer to work in-person are stuck. Teachers need different options to choose from, just like families.

Choice would also be good for teacher pay, by the way. No longer stuck with a monopoly employer, teachers would have the power to demand higher salaries, or better perks, than what their unions decide to accept. And schools, which would compete for students based on the effectiveness of their instruction, among other things, would have strong incentives to pay more for good teachers.

COVID-19 has driven home how important freedom is for children. But it is also important for teachers, even if their unions insist on standing in the way.