While there’s been thousands of legacy media stories about the very real decline in summer sea-ice extent in the Arctic Ocean, we can’t find one about the statistically significant increase in Antarctic sea ice that has been observed at the same time.

Also, comparisons between forecast temperature trends down there and what’s been observed are also very few and far between. Here’s one published in 2015:

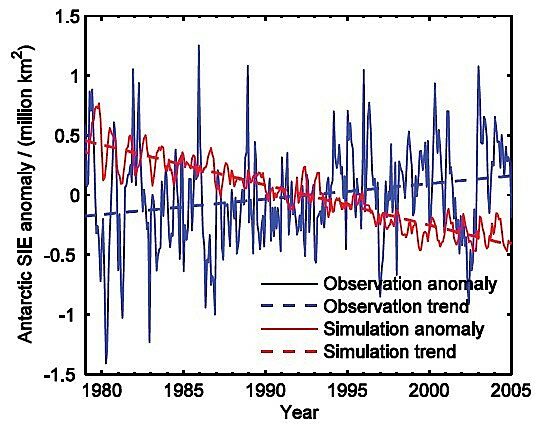

Observed (blue) and model-forecast (red) Antarctic sea-ice extent published by Shu et al. (2015) shows a large and growing discrepancy, but for unknown reasons, their illustration ends in 2005.

For those who utilize and trust in the scientific method, forming policy (especially multi-trillion dollar policies!) on the basis of what could or might happen in the future seems imprudent. Sound policy, in contrast, is best formulated when it is based upon repeated and verifiable observations that are consistent with the projections of climate models. As shown above, this does not appear to be the case with the vast ice field that surrounds Antarctica.

According to the most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), CO2-induced global warming will result in a considerable reduction in sea ice extent in the Southern Hemisphere. Specifically, the report predicts a multi-model average decrease of between 16 and 67 percent in the summer and 8 to 30 percent in the winter by the end of the century (IPCC, 2013). Given the fact that atmospheric CO2 concentrations have increased by 20 percent over the past four decades, evidence of sea ice decline should be evident in the observational data if such model predictions are correct. But are they?

Thanks to a recent paper in the Journal of Climate by Josefino Comiso and colleagues, we now know what’s driving the increase in sea-ice down there. It’s—wait for it—cooling temperatures over the ocean surrounding Antarctica.

This team of six researchers set out to produce an updated and enhanced dataset of sea ice extent and area for the Southern Hemisphere for the period 1978 to 2015. The key enhancement over prior datasets included an improved cloud masking technique that eliminated anomalously high or low sea ice values, assuring that their work is the most definitive study of Antarctic sea ice trends to date.

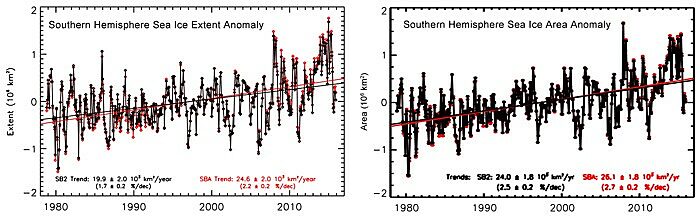

The six scientists report the existence of a long-term increasing trend in both sea ice extent and area over the period of study (see figure below), with the former measure increasing by 1.7 percent per decade and the latter by 2.5 percent per decade.

Figure 1. Monthly anomalies of Southern Hemisphere sea ice extent (left panel) and area (right panel) derived using the newly enhanced SB2 data (black) of Comiso et al. and the older SBA data (red) prior to the enhancements made by Comiso et al. Trend lines for each data set are also shown and the trend values with statistical errors are provided. Source: Comiso et al. (2017).

With regard to these observed increases, Comiso et al. confirm “the trend in Antarctic sea ice cover is positive,” adding “the trend is even more positive than previously reported because prior to 2015 the sea ice extent was anomalously high for a few years, with the record high recorded in 2014 when the ice extent was more than 20 x 106 km2 for the first time during the satellite era.”

They compared satellite-based estimates of temperature over the ocean/ice and found a very high negative correlation between ice cover and temperature. So, the large and systematic increase in ice extent must be related to a cooling over the sea-ice region throughout the 36-year period of record in this study.

Why is this important? Much like the problems with the missing “tropical hot spot” we noted last month, Antarctic sea-ice modulates a cascade of meteorology. When it’s gone, or in decline, as is the forecast from the climate models, much more of the sun’s energy goes into the ocean, as that energy is only very poorly absorbed by ice, which means an enhanced warming of the Southern Ocean. That has effects on Antarctica itself, where slightly warmed surrounding waters will dramatically increase snowfall on the continent. The fact that there are only glimmerings of this showing up (if at all) should have tipped people off that something was very wrong with the temperature forecast for the nearby ocean.

Consequently, it is clear that despite a 20 percent increase in atmospheric CO2, and model predictions to the contrary, sea ice in the Antarctic has expanded for decades. Such observations are in direct opposition to the model-based predictions of the IPCC.

(N.B. as noted in our May Day post, the Antarctic ice sensor crashed last April, and subsequent data appears to be very unreliable and, in some cases, physically impossible.)

References:

Comiso, J.C., Gersten, R.A., Stock, L.V., Turner, J., Perez, G.J. and Cho, K. 2017. Positive trend in the Antarctic sea ice cover and associated changes in surface temperature. Journal of Climate 30: 2251–2267.

IPCC. 2013. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp.

Shu, Q., et al., 2015. Assessment of sea ice simulations in the CMIP5 models. The Cryosphere 9, 399–409.