Last week officers with the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department arrested Joseph James DeAngelo, the suspected Golden State Killer who allegedly committed a dozen murders, at least 50 rapes, and more than 100 burglaries in California between 1976 and 1986. Police made the arrest after uploading DeAngelo’s “discarded DNA” to one of the increasingly popular genealogy websites. Using information from the site, investigators were able to find DeAngelo’s distant relatives, thereby significantly narrowing their list of suspects. This investigatory technique is worth keeping an eye on, not least because millions of people are using DNA-based genealogical sites.

I’m one of them. I’ve signed up to 23andMe as well as MyHeritage, both of which offer DNA analysis. I did this in part because family history is a minor hobby of mine, but also because 23andMe offers interesting medical information. While both companies offer a DNA service, I’ve only used 23andMe’s because MyHeritage allows its users to upload 23andMe data. One of the features of MyHeritage is its “DNA Matching” service, which updates me when a distant relative is found thanks to automated DNA analysis.

This month alone MyHeritage has altered me to the existence of two more 3rd — 5th cousins. This DNA Matching service has identified hundreds of my distant relatives, with varying degrees of confidence. 23andMe has a similar relative-finding feature. MyHeritage and 23andMe, as well as Ancestry.com, have all denied working with law enforcement in the Golden State Killer case.

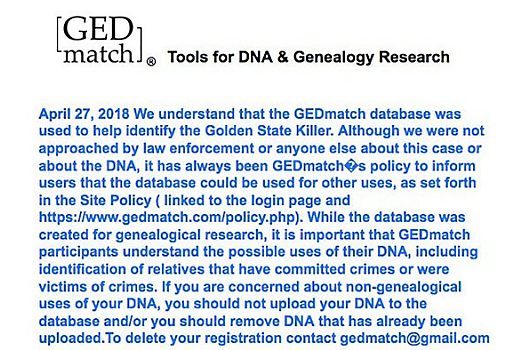

According to The New York Times, investigators sent the suspected Golden State Killer’s DNA to GEDmatch, a free genealogical service. A GEDmatch release stated that it had not been approached by law enforcement and warned customers, “If you are concerned about non-genealogical uses of your DNA, you should not upload your DNA to the database.”

The Times report included this important paragraph:

The detectives in the Golden State Killer case uploaded the suspect’s DNA sample. But they would have had to check a box online certifying that the DNA was their own or belonged to someone for whom they were legal guardians, or that they had “obtained authorization” to upload the sample.

Investigators obviously didn’t have DeAngelo’s authorization. However, it’s unlikely that they were constitutionally required to obtain it. From Technology Review:

[GEDmatch co-creator] Rogers didn’t say whether he thought police had acted legally or not, but he says the rule on his website is that “it’s only with a person’s permission.”

Investigators, of course, didn’t have authorization from DeAngelo to use his DNA. However, it seems likely they would not have needed it. “Under current constitutional law, the government has a tremendous amount of discretion in how to use crime-scene evidence,” says Erin Murphy, a professor of law at New York University. “DNA abandoned by the perpetrator of a crime basically has no legal protection.”

What’s particularly interesting about this case is that it doesn’t involve police identifying a GEDmatch customer as a suspect and then seeking that suspect’s DNA profile as part of an investigation. Rather, investigators used GEDmatch to build a family tree of the suspect based on information GEDmatch customers had volunteered. GEDmatch’s website includes this warning, “DNA and Genealogical research, by its very nature, requires the sharing of information. Because of that, users participating in this site should expect that their information will be shared with other users.”

23andMe and Ancestry.com both mention law enforcement in their privacy policies. These policies discuss law enforcement in the context of law enforcement seeking customers’ data. For instance, 23andMe’s policy states (emphasis mine), “Under certain circumstances your information may be subject to disclosure pursuant to judicial or other government subpoenas, warrants, or orders” and Ancestry.com’s policy includes the following, “We may share your Personal Information if we believe it is reasonably necessary to […] Comply with valid legal process (e.g., subpoenas, warrants).”

It’s laudable that these private companies have made commitments to protect their customers’ privacy, but the Golden State Killer investigation did not rely on investigators directly accessing GEDmatch customers’ information. Rather, it relied on GEDmatch to do what it’s product is designed to do: find relatives.

Law enforcement use of genealogical sites is a rare investigatory technique. According to a 23andMe spokesperson, the company has only “had a handful of inquiries over the course of 11 years.” Ancestry.com’s 2017 transparency report revealed that the company had only received 34 valid law enforcement requests that year, only 19 of which came from American law enforcement agencies. Each one of these 34 requests related to credit card fraud or identity theft.

Although rare, we should prepare for a time when this kind of investigation is widespread. I doubt that any of DeAngelo’s distant relatives will be upset that their genetic information was used to aid an investigation into a serial killer and rapist, but we should consider what law enforcement looks like in a world where “genetic informants” are commonplace. As UC Davis Law Professor Elizabeth Joh told The New Republic, “Do you realize, for example, that when you upload your DNA, you’re potentially becoming a genetic informant on the rest of your family? […] And then if that’s the case, what if you’re the person who didn’t personally upload the DNA, but you discover that your family member has done that?”